This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 85.91.136.12 (talk) at 04:59, 19 April 2006 (→The Jot {{IPA|/j/}} - Semivowel and Palatalisation). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:59, 19 April 2006 by 85.91.136.12 (talk) (→The Jot {{IPA|/j/}} - Semivowel and Palatalisation)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Bulgarian | |

|---|---|

| Български Bǎlgarski | |

| Native to | Bulgaria, Ukraine, Moldova, the Western Outlands region in Serbia and Montenegro, Romania, Republic of Macedonia, Greece and among emigrant communities around the world |

| Region | The Balkans |

| Native speakers | approx. 10 million, incl. 1.5–2 million second-language speakers 8.9 million (Ethnologue) |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

| Official status | |

| Official language in | Bulgaria |

| Regulated by | Institute of Bulgarian at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (Институт за български език) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | bg |

| ISO 639-2 | bul |

| ISO 639-3 | bul |

Bulgarian is an Indo-European language, a member of the Southern branch of the Slavic languages. Bulgarian demonstrates several linguistic innovations that set it apart from other Slavic languages, such as the elimination of noun declension, the development of a suffixed definite article (see Balkan linguistic union), the lack of a verb infinitive, and the retention and further development of the proto-Slavic verb system. There are various verb forms to express nonwitnessed, retold, and doubtful action.

Bulgarian is closely related to the Macedonian language. The prevalent opinion in Bulgaria is that Macedonian is a literary variant of the Bulgarian language (though most non-Bulgarian linguists dispute this). Bulgarian and Macedonian form part of the Balkan linguistic union, which also includes Greek, Romanian, Albanian and some Serbian dialects. Most of these languages share some of the above-mentioned characteristics (e.g., definite article, infinitive loss, complicated verb system) and many more. The "nonwitnessed action" verb forms, pertaining to a mood known as renarrative mood, have been attributed to Turkish influences by most Bulgarian linguists. Morphohologically, they are related to the perfect tenses, which are known in Bulgarian linguistic tradition as "preliminary" (предварителни) tenses.

History

Main article: History of BulgarianThe development of the Bulgarian language may be divided into several historical periods. The prehistoric period (essentially proto-Slavic) occurred between the Slavonic invasion of the eastern Balkans and the mission of St. Cyril and St. Methodius to Great Moravia in the 860s. Old Bulgarian (9th to 11th century, also referred to as Old Church Slavonic) was the language used by St. Cyril, St. Methodius and their disciples to translate the Bible and other liturgical literature from Greek. Middle Bulgarian (12th to 15th century) was a language of rich literary activity and major innovations. Modern Bulgarian dates from the 16th century onwards; the present-day written language was standardized on the basis of the 19th-century Bulgarian vernacular. The historical development of the Bulgarian language can be described as a transition from a highly synthetic language (Old Bulgarian) to a typical analytic language (Modern Bulgarian) with Middle Bulgarian as a midpoint in this transition.

Fewer than 20 words remain in Bulgarian from the language of the Bulgars, the Central Asian people who moved into present-day Bulgaria and eventually adopted the local Slavic language. The Bolgar language, a member of the Turkic language family or the Iranian language family (Pamir languages), is otherwise unrelated to Bulgarian.

Old Bulgarian was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, in the oldest manuscripts this language was initially referred to as языкъ словяньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name языкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, the name языкъ блъгарьскъ was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of St. Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid in the 11th century, for example in the Greek hagiography of Saint Clement of Ohrid by Theophylact of Ohrid (late 11th century).

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Old Slavonic case system, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in most other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbours in the Balkan linguistic union (mostly grammatically) and later also by Turkish, which was the official language of Ottoman empire in the form of the Ottoman language (an earlier former of Turkish), mostly lexically. As a national revival occurred towards the end of the period of Ottoman rule (mostly during the 19th century), a modern Bulgarian literary language gradually emerged which drew heavily on Russian and Church Slavonic/Old Bulgarian and which later reduced the number of Turkish and other Balkanic loans.

Modern Bulgarian was based essentially on the Eastern dialects of the language, but its pronunciation is in many respects a compromise between East and West Bulgarian (see especially the phonetic sections below).

Alphabet

In 886 AD, Bulgaria adopted the Glagolitic alphabet which was devised by the Byzantine missionaries Saint Cyril and Methodius in the 850s. The Glagolitic alphabet was gradually superseded in the following centuries by the Cyrillic alphabet, which was developed around the Preslav Literary School in the beginning of the 10th century. Most of the letters in the Cyrillic alphabet were borrowed from the Greek alphabet; those which had no Greek equivalents, however, represent simplified Glagolitic letters.

Under the influence of printed books from Russia, the Russian "civil script" of Peter I (see Reforms of Russian orthography) replaced the old Middle Bulgarian/Church Slavonic script at the end of the 18th century. Several Cyrillic alphabets with 28 to 44 letters were used in the beginning and the middle of the 19th century during the efforts on the codification of Modern Bulgarian until an alphabet with 32 letters, proposed by Marin Drinov, gained prominence in the 1870s. The alphabet of Marin Drinov was used until the orthographic reform of 1945 when the letters yat (Ѣ, ѣ, called "double e"), and yus (Ѫ, ѫ) were removed from the alphabet. The present Bulgarian alphabet has 30 letters.

The following table gives the letters of the Bulgarian alphabet, along with IPA values for the sound of each letter:

| А а /a/ |

Б б /b/ |

В в /v/ |

Г г /g/ |

Д д /d/ |

Е е /ɛ/ |

Ж ж /ʒ/ |

З з /z/ |

И и /i/ |

Й й /j/ |

| К к /k/ |

Л л /l/ |

М м /m/ |

Н н /n/ |

О о /ɔ/ |

П п /p/ |

Р р /r/ |

С с /s/ |

Т т /t/ |

У у /u/ |

| Ф ф /f/ |

Х х /x/ |

Ц ц /ʦ/ |

Ч ч /tʃ/ |

Ш ш /ʃ/ |

Щ щ /ʃt/ |

Ъ ъ /ɤ/ |

Ь ь /ʲ/ |

Ю ю /ju/ |

Я я /ja/ |

softens consonants before 'o'

Most letters in the Bulgarian alphabet stand for one specific sound and that sound only. Three letters stand for the single expression of combinations of sounds, namely щ (sht), ю (yu), and я (ya). Two sounds do not have separate letters assigned to them, but are expressed by the combination of two letters, namely дж (like j in Jack) and дз (dz). The letter ь is not pronounced, but it softens (palatalizes) any preceding consonant before the letter о.

For questions regarding the transliteration of Bulgarian into the Latin alphabet (romanization), see romanization of Bulgarian.

Phonology

Vowels

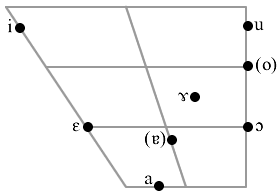

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | и /i/ | у /u/ | |

| Mid | е /ɛ/ | ъ /ɤ/ | о /ɔ/ |

| Low | а /a/ |

Bulgarian's six vowels may be grouped in three pairs according to their backness: front, central and back. All vowels are relatively lax, as in most other Slavic languages, and unlike the tense vowels, for example, in the Germanic languages. Unstressed vowels tend to be shorter and weaker compared to their stressed counterparts, and the corresponding pairs of open and closed vowels approach each other with a tendency to merge, above all as open (low and middle) vowels are raised and shift towards the narrow (high) ones. However, the coalescence is not always complete. The vowels may be distinguished in emphatic or deliberately distinct pronunciation, and the variation of the norm is socially conditioned, too: while the relative absence of reduction is intuitively associated with certain types of low-status (provincial, especially West Bulgarian, or Romani-influenced) speech, the awareness of the distinctions is naturally perceived as a sign of literacy and education. Therefore, reduction is strongest in colloquial speech (where unstressed syllables can even be deleted in some instances). Besides that, some linguists distinguish two degrees of reduction and have found that a slight distinction tends to be maintained in the syllable immediately preceding the stressed one. Many Bulgarian prescriptivists seem inclined to view the complete merger of the pair/a/ - /ɤ/ most favourably, while conisdering the status of /ɔ/ vs /u/ (phonetically ?) to be less clear, even though the latter merger is as complete as to cause spelling mistakes. A coalescence of /ɛ/ and /i/ is definitely not allowed in formal speech and is regarded as a provincial (East Bulgarian) feature; since /ɛ/ is nevertheless reduced (raised) in unstressed position, the acoustic impression of it might occasionally resemble a more front form of /ɤ/.

The Jot /j/ - Semivowel and Palatalisation

Bulgarian language possesses one semivowel: /j/, being equivalent to y in English like in yes. J is used and indicates palatalisation of consonants too. See more about it here, in this article, section Palatalisation.

/j/ is signified in four ways in Bulgarian language:

- As it is - й(j) (called и кратко "short i" or archaically as йота, йот, jot). This is when it:

- precedes о, Йогурт (jогурт)

- is at the end of words, асемблирай (асемблираj)

- precedes e, йее (jee, means yeah)

- Like я (ja):

- when precedes the vowel a - jotation of a is indicated as я, nor j, nor a is written. In this case it is not preceded with consonant. Especially at the beginning or end of the word. Ягода (strawberry), тлея (smoulder). But also преяждам (overeat).

- when to indicate palatalised consonant, and again being before vowel a is indicated as я, nor j, nor a is written. Напряко (across).

- As ю (ju):

- when precedes bulgarian vowel у (u, like u i clue) - jotation of у is indicated as ю, nor j, nor у is written. In this case it is not preceded with consonant. Especially beginnings of words. Юпи, юли.

- when to indicate palatalised consonant, before vowel у, indicated as ю, nor j, nor у is written. Плюя.

- As ь in ьо (jo), i.e. before о - the two go only in combination. Like in the words сульо, пульо. Ьо is basically the same as йо(look over 1.a.), and is commonly mistaken with it, also because of ьо is rear in use. The rule is that you write йо at the beginning of words and ьо never at the beginning. Also ьо comes after consonant like in пльос, but йо is after a vowel крайов (dialect saying)

The /j/ always immediately precedes or follows a vowel. The semivowel is most usually expressed graphically by the letter й, as, for example, in най /naj/ ("most") and тролей /trɔlɛj/ ("trolleybus"). The letters ю and я are, however, also used, for example, ютия /jutija/ "(flat) iron". Most rear use is of combination ьо. The letter ь is never written alone, unlike in russian for exaple, and always indeicates palatalisation preceding o.

NB: After a consonant, ю and я signify a palatalized consonant rather than a semivowel: бял /bʲal/ "white".

Consonants

Bulgarian has a total of 33 consonant phonemes (see table below). Three additional phonemes can also be found (, and ), but only in foreign proper names such as Хюстън /xʲustɤn/ ("Houston"), Дзержински /dzɛrʒinski/ ("Dzerzhinsky"), and Ядзя /jaʣʲa/, the Polish name "Jadzia". They are, however, normally not considered part of the phonetic inventory of the Bulgarian language. According to the criterion of sonority, the Bulgarian consonants may be divided into 16 pairs (voiced<>voiceless). The only consonant without a counterpart is the voiceless velar fricative . The contrast 'voiced vs. voiceless' is neutralized in word-final position, where all consonants are pronounced as voiceless (as in most Slavic languages, German, etc.); this neutralization is, however, not reflected in the spelling.

Hard and palatalized consonants

The Bulgarian consonants б /b/, в /v/, г /g/, д /d/, з /z/, к /k/, л /l/, м /m/, н /n/, п /p/, р /r/, с /s/, т /t/, ф /f/, ц /ʦ/ can have both a normal, "hard" pronunciation, as well as a "soft", palatalized one. The hard and the palatalized consonants are considered separate phonemes in Bulgarian. The consonants ж /ʒ/, ш /ʃ/, ч /ʧ/ and дж /ʤ/ do not have palatalized variants, which is probably connected with the fact that they have arisen historically through palatalization in common Slavic. These consonants may be realized with different grades of hardness or softness, depending on speaker and dialect; a relatively neutral realization is perceived as standard.

The softness of the palatalized consonants is always indicated in writing in Bulgarian. A consonant is palatalized if:

- it is followed by the soft sign ь;

- it is followed by the letters я / ʲa/ or ю / ʲu/;

(я and ю are used in all other cases to represent the semivowel /j/ before /a/ and /u/.)

Even though palatalized consonants are phonemes in Bulgarian, they may in some cases be positionally conditioned, hence redundant. In Eastern Bulgarian dialects, consonants are always allophonically palatalized before the vowels /i/ and /ɛ/. This is not the case in correct Standard Bulgarian, but that form of the language does have similar allophonic alternations. Thus, к /k/, г /g/ and х /x/ tend to be palatalized before /i/ and /ɛ/, and the realization of the phoneme л /l/ varies along the same principles: it is velarized in all positions, except before the vowels /i/ and /ɛ/. The normal, non-velarized realization is traditionally (and incorrectly) called 'soft l', even though it is not palatalized (and thus isn’t identical to the /lʲ/ signalled by the letters ь, я and ю). In many Western Bulgarian dialects, as well as in the neighbouring Serbian language, this 'pseudo-soft' realization does not exist and the nonpalatalized /l/ is always velarized regardless of the quality of the following vowels.

Furthermore, in the speech of young people, especially in the capital, the velarized allophone of /l/ is often realized as something resembling a labial-velar approximant , a semivowel or even an . Similar developments, termed L-vocalization, have occurred in many languages, including Cockney English.

Palatalization

During the palatalization of most hard consonants (the bilabial, labiodental and alveolar ones), the middle part of the tongue is lifted towards the palatum, resulting in the formation of a second articulatory centre whereby the specific palatal "clang" of the soft consonants is achieved. The articulation of alveolars /l/, /n/ and /r/, however, usually does not follow that rule; the palatal clang is achieved by moving the place of articulation further back towards the palatum so that /ʎ/, /ɲ/ and /rʲ/ are actually alveopalatal (postalvelolar) consonants. Soft /g/ and /k/ (/gʲ/ and /kʲ/, respectively) are articulated not on the velum but on the palatum and are considered palatal consonants.

Table of Bulgarian consonants

Word stress

Word stress in Bulgarian is not signified in written text and words usually, only rearly is made an exception of this rule. Stressed syllables are louder and longer than unstressed ones. Bulgarian word stress is dynamic. This is no rule stress unlike french or latin, stress has accidential plce in word, and also changes its place in word's forms. So thus stress is free and mobile, it may fall on any syllable of a polysyllabic word and its position may vary in inflection and derivation, for example, мъж /mɤʃ/ ("man"), мъжът /mɤ'ʒɤt/ ("the man"). Bulgarian stress is also distinctive: for example words в'ълна /'vɤlna/ ("wool") and вълн'а /vɤl'na/ ("wave") are only indentified and differentiated by its stress. In case like this stress maybe put on writen text, elsewise stress may be given in dialect words, to signify the diference from literary language pronunciation.

Grammar

| It has been suggested that this article be merged into Bulgarian grammar. (Discuss) |

There is some more information at Bulgarian grammar

The parts of speech in Bulgarian are divided in 10 different types, which are categorized in two broad classes: mutable and immutable. The difference is that mutable parts of speech vary grammatically, whereas the immutable ones do not change, regardless of their use. The five classes of mutables are: nouns, adjectives, numerals, pronouns and verbs. Syntactically, the first four of these form the group of the noun or the nominal group. The immutables are: adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, particles and interjections. Verbs and adverbs form the group of the verb or the verbal group.

Nominal morphology

Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are inflected for grammatical gender, number, case (to a very limited extent) and definiteness in Bulgarian. Adjectives and adjectival pronouns agree with nouns in number and gender.

Nominal inflection

Gender

There are three grammatical genders in Bulgarian: masculine, feminine and neuter. The gender of the noun can largely be determined according to its ending. The vast majority of Bulgarian nouns ending in a consonant (zero ending) are masculine (for example, град “city”, син “son”, мъж “man”). Feminine nouns include almost all nouns that have the endings –а/–я (жена “woman”, дъщеря “daughter”, улица “street”), a large group of nouns with zero ending expressing quality, degree or an abstraction, including all nouns ending on –ост/–ест (мъдрост “wisdom”, низост “vileness”, прелест "loveliness", болест "sickness", любов “love”), and another, much smaller group of irregular nouns with zero ending which define tangible objects or concepts (кръв “blood”, кост “bone”, вечер “evening”). Nouns ending in –е, –о are almost exclusively neuter (дете “child”, езеро “lake”). The same regards a limited number of loan words ending in –и, –у, and –ю (цунами "tsunami", табу "taboo", меню "menu"). Plural nouns do not have gender.

Number

Two numbers are distinguished in Bulgarian — singular and plural. The most typical plural ending for feminine nouns is –и, which is appended to the word upon dropping the singular ending –а/–я. Plural forms of neutral and masculine nouns use a variety of suffixes, the most typical of which are –а, –я (both require dropping of the singular endings –е/–о) and –та for neutral nouns and –е, –и and –ове for masculine nouns. Exceptions, irregular declension and alternative plural forms are, however, very common for all three genders.

Masculine nouns use a separate count form with cardinal numbers, which stems from the proto-Slavonic dual: двама/трима ученика (two/three students) versus тези ученици (these students); cf. feminine две/три/тези жени (two/three/these women) and neuter две/три/тези деца (two/three/these children). However, a recently developed language norm requires that count forms should only be used with masculine nouns that do not denote persons. Thus, двама/трима ученици is perceived as more correct than двама/трима ученика, while the distinction is retained in cases such as два/три молива (two/three pencils) versus тези моливи (these pencils).

Case

The complex proto-Slavonic case system is almost completely dissolved in modern Bulgarian. Vestiges are well preserved only in the personal pronouns and the masculine personal interrogative pronoun кой (“who”), which have nominative, accusative and dative forms. Vocative forms are still in use for masculine and feminine nouns (however, not for neuter ones), but endings in masculine nouns are determined solely according to the stem-final consonant of the noun. In all other cases, except for a number of phraseological units and sayings, the proto-Slavonic case system has been replaced by prepositional and other syntactic constructions.

Definiteness (article)

The disappearance of the case declension might be connected with the development of the category of definiteness in Bulgarian. The postfixed definite article, which displaced Slavic case inflexions, may have been inherited from Old Bulgar and then spread to other Balkan languages such as Albanian and Romanian. In modern Bulgarian, definiteness is expressed by a definite article which is postfixed to the noun (indefinite: човек, “man”; definite: човекът, “the man”) or the first nominal constituent of definite noun phrases (indefinite: добър човек, “a good man”; definite: добрият човек, “the good man”), much like in the Scandinavian languages or Romanian. There are four singular definite articles: –ът/–ят for masculine nouns that are grammatical subjects, –а/–я for masculine nouns that are grammatical objects, –та for feminine nouns, and –то for neuter nouns. The two masculine definite articles may also be considered as two grammatical forms of the same article. The plural definite articles are –те for masculine and feminine nouns, and –тa for neuter nouns. When postfixed to adjectives the definite articles are –ят/–я for masculine, –та for feminine, –то for neuter, and –те for plural nouns.

Adjective and numeral inflection

Both groups agree in gender and number with the noun they are appended to. They may also take up the definite article as explained above.

Pronouns

Pronouns may vary in gender, number, definiteness and are the only parts of speech that have retained case inflexions. Three cases are exhibited by some groups of pronouns, nominative, accusative and dative, although dative is often substituted by accusative constructions. The distinguishable types of pronouns include the following: personal, relative, reflexive, interrogative, negative, indefinitive, summative and possessive.

Adverbs

The most productive way to form adverbs is to derive them from the neuter singular form of the corresponding adjective (бързо (fast), силно (hard), странно (strangely)), although adjectives ending in -ки use the masculine singular form, also in -ки, instead: юнашки (heroically), мъжки (bravely, like a man), майсторски (skilfully). The same pattern is used to form adverbs from the (adjective-like) ordinal numerals, e.g. първо (firstly), второ (secondly), трето (thirdly), and in some cases from (adjective-like) cardinal numerals, e.g. двойно (twice as/double), тройно (three times as), петорно (five times as).

The remaining adverbs are formed in ways that are no longer productive in the language. A small number are original (not derived from other words), for example: тук (here), там (there), вътре (inside), вън (outside), много (very/much) etc. The rest are mostly fossilized declined forms, such as:

- archaic unchangeable locative forms of some adjectives, e.g. добре (well), зле (badly), твърде (too, rather), and nouns горе (up), утре (tomorrow), лете (in the summer);

- archaic unchangeable instrumental forms of some adjectives, e.g. тихом (quietly), скришом (furtively), слепешком (blindly), and nouns, e.g. денем (during the day), нощем (during the night), редом (one next to the other), духом (spiritually), цифром (in figures), словом (with words). The same pattern has been used with verbs: тичешком (while running), лежешком (while lying), стоешком (while standing).

- archaic unchangeable accusative forms of some nouns: днес (today), сутрин (in the morning), зимъс (in winter);

- archaic unchangeable genitive forms of some nouns: довечера (tonight), снощи (last night), вчера (yesterday);

- homonymous and etymologically identical to the feminine singular form of the corresponding adjective used with the definite article: здравата (hard), слепешката (gropingly); the same pattern has been applied to some verbs, e.g. тичешката (while running), лежешката (while lying), стоешката (while standing).

- derived from cardinal numerals by means of a non-productive suffix: веднъж (once), дваж (twice), триж (thrice);

All the adverbs are immutable. Verb forms, however, vary in aspect, mood, tense, person, number and sometimes gender and voice.

Verbal morphology and grammar

Finite verbal forms

Finite verbal forms are simple or compound and agree with subjects in person (first, second and third) and number (singular, plural) in Bulgarian. In addition to that, past compound forms using participles vary in gender (masculine, feminine, neuter) and voice (active and passive) as well as aspect (perfective/aorist and imperfective).

Aspect

Bulgarian verbs express lexical aspect: perfective verbs signify the completion of the action of the verb and form past aorist tenses; imperfective ones are neutral with regard to it and form past imperfect tenses. Most Bulgarian verbs can be grouped in perfective-imperfective pairs (imperfective<>perfective: идвам<>дойда “come”, пристигам<>пристигна “arrive”). Perfective verbs can be usually formed from imperfective ones by suffixation or prefixation, but the resultant verb often deviates in meaning from the original. In the pair examples above, aspect is stem-specific and therefore there is no difference in meaning.

In Bulgarian, there is also grammatical aspect. Three grammatical aspects are distinguishable: neutral, perfect and pluperfect. The neutral aspect comprises the three simple tenses and the future tense. The pluperfect aspect is manifest in tenses that use double or triple auxiliary "be" participles like the past pluperfect subjunctive. Perfect tenses use a single auxiliary "be".

Mood

In addition to the four moods (наклонения) shared by most other European languages - indicative (изявително), imperative (повелително), subjunctive (подчинително) and conditional (условно) - in Bulgarian there is one more to describe past unwitnessed events - the renarrative (преизказно) mood.

Tense

There are three grammatically distinctive positions in time — present, past and future — which combine with aspect and mood to produce a number of formations. Normally, in grammar books these formations are viewed as separate tenses — i. e. "past imperfect tense" would mean that the verb is in past tense, in the imperfective aspect, and in the indicative mood (since no other mood is shown). There are more than 30 different tenses across Bulgarian's two aspects and five moods.

In the indicative mood, there are three simple tenses:

- present tense is a temporally unmarked simple form made up of the verbal stem of and a complex suffix composed of the vowel /e/, /i/ or /a/ and the person/number ending (пристигам "I arrive/I am arriving"); only imperfective verbs can stand in the present indicative tense independently;

- past imperfect tense is a simple verb form used to express an action which is contemporaneous or subordinate to other past actions; it is made up of an imperfective verbal stem and the person/number ending (пристигаx "I was arriving");

- past aorist tense is a simple form used to express a temporarily independent, specific past action; it is made up of a perfective verbal stem and the person/number ending (пристигнах "I arrived");

In the indicative there are also the following compound tenses:

- future tense is a compound form made of the particle ще and present tense (ще уча "I will study"); negation is expressed by the construction няма да and present tense (няма да уча "I will not study");

- past future tense is a compound form used to express an action which was to be completed in the past but was future as regards another past action; it is made up of the past imperfect tense of the verb ща "will, want", the particle да "to" and the present tense of the verb (щях да уча "I was going to study");

- present perfect tense is a compound form used to express an action which was completed in the past but is relevant for or related to the present; it is made up of the present tense of the verb съм "be" and the past participle (съм учил "I have studied");

- past perfect tense is a compound form used to express an action which was completed in the past and is relative to another past action; it is made up of the past tense of the verb съм "be" and the past participle (бях учил "I had studied");

- future perfect tense is a compound form used to express an action which is to take place in the future before another future action; it is made up of the future tense of the verb съм "be" and the past participle (ще съм учил "I will have studied");

- past future perfect tense is a compound form used to express a past action which is future with respect to a past action which itself is prior to another past action; it is made up of the past future of ща "will, want", the particle да "to", the present tense of the verb съм "be" and the past participle of the verb (щях да съм учил "I would have studied").

The four perfect tenses above can all vary in aspect depending on the aspect of the main-verb participle; they are in fact pairs of imperfective and perfective tenses. Verbs in tenses using past participles also vary in voice and gender.

There is only one simple tense in the imperative mood - the present - and there are simple forms only for the second person using the suffixes -и/-й for singular and -ете/-йте for plural; e.g., уча "to study": учи, sg., учете, pl.; играя "to play": играй, играйте. There are compound imperative forms for all persons and numbers in the present compound imperative (да играе) and the present perfect compound imperative (да е играл).

The conditional mood consists of five compound tenses, most of which are not grammatically distinguishable. The present, future and past conditional use a special past form of the stem би- (“be”) and the past participle (бих учил, “I would study”). The past future conditional and the past future perfect conditional coincide in form with the respective indicative tenses.

The subjunctive mood is rarely documented as a separate verb form in Bulgarian, (being, morphologically, a sub-instance of the quasi-infinitive construction with the particle да 'to' and a normal finite verb form), but nevertheless it is used regularly. The most common form, often mistaken for the present tense, is the present subjunctive ((пo-добре) да отидa "I had better go"). The difference between the present indicative and the present subjunctive tense is that the subjunctive can be formed by both perfective and imperfective verbs. It has completely replaced the infinitive and the supine from complex expressions (see below). It is also employed to express opinion about possible future events. The past perfect subjunctive ((пo-добре) да бях отишъл, "I had better gone") refers to possible events in the past, which did not take place, and the present pluperfect subjunctive (да съм бил отишъл), which may be used about both past and future events arousing feelings of incontinence, suspicion, etc. and is impossible to translate in English. This last variety of the subjunctive in Bulgarian is sometimes also called the dubitative mood.

The renarrative mood has five tenses. Two of them are simple - past aorist renarrative and past imperfect renarrative - and are formed by the past participles of perfective and imperfective verbs, respectively. There are also three compound tenses - past future renarrative, past future perfect renarrative and past perfect renarrative. All these tenses' forms are gender-specific in the singular and exist only in the third person.

Non-finite verbal forms

The proto-Slavonic infinitive and supine have been replaced by phrases with да (“to”) and present subjunctive tense (искам да уча, “I want to study”).

Bulgarian has the following participles:

- the present active participle (сегашно деятелно причастие) is formed from imperfective stems with the addition of the suffixes –ащ/–ещ/–ящ (укриващ, “concealing”) and is used only attributively;

- the present passive participle (сегашно страдателно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffix -н to imperfective stems (укриван, “(being) concealed”);

- the past active aorist participle (минало свършено деятелно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffix –л– to perfective stems (укрил, “concealed”);

- the past active imperfect participle (минало несвършено деятелно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffixes –ел/–ал/–ял to imperfective stems (укривал, “(been) concealing”); it is used only in renarrative (renarrated) mood and is a Bulgarian innovation;

- the past passive participle (минало страдателно причастие) is formed from aorist stems with the addition of the suffixes –(е)н–/–т– (укрит, "(been) concealed"); it is used predicatively and attributively;

- the adverbial participle (деепричастие) is formed from imperfective present stems with the suffix –(е)йки (укривайки, “while concealing”), relates an action contemporaneous with and subordinate to the main verb and is originally a Western Bulgarian form.

The participles are inflected by gender, number, and definiteness, and are coordinated with the subject when forming compound tenses (see tenses above). When used in attributive role the inflection attributes are coordinated with the noun that is being attributed.

Lexis

Main article: Bulgarian lexis

Most of the word-stock of modern Bulgarian consists of derivations of some 2,000 words inherited from proto-Slavonic through the mediation of Old and Middle Bulgarian. The influence of the old Bolgar language is relatively insignificant, and a negligible number of words of presumably Bulgar origin have survived in Modern Bulgarian (20 at best according to most estimates, though some scholars will have that number increased up to 200). Thus, the native lexical terms in Bulgarian (both from proto-Slavonic and from the Bulgar language) account for 70% to 75% of the lexicon.

The remaining 25% to 30% are loanwords from a number of languages, as well as derivations of such words. The languages which have contributed most to Bulgarian are Latin and Greek (mostly international terminology), and to a lesser extent French and Russian. The numerous loanwords from Turkish (and, via Turkish, from Arabic and Persian) which were adopted into Bulgarian during the long period of Ottoman rule have, to a great extent, been substituted with native terms or borrowings from other languages. As in much of the rest of the world, English has had the greatest influence over Bulgarian over recent decades.

Syntax

Colloquial Bulgarian employs clitic doubling, mostly for emphatic purposes. For example:

- Аз го дадох подаръка на майка ми

- (lit. "I gave it the present to my mother")

- Аз й го дадох подаръка на майка ми

- (lit. "I gave her it the present to my mother")

The phenomenon is practically obligatory in the case of inversion signalling information structure:

- Подаръка (й) го дадох на майка ми

- (lit. "The present (to her) it I-gave to my mother")

- На майка ми й (го) дадох подаръка

- (lit. "To my mother to her (it) I-gave the present").

In a formal context, however, no clitic doubling is allowed. Bulgarian grammars usually do not treat this phenomenon extensively.

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Common Bulgarian expressions

- Здравей (zdravéi) — Hello

- Здрасти (zdrásti) — Hi

- Добро утро (dobró útro) — Good morning

- Добър ден (dóbər dén) — Good day

- Добър вечер (dóbər vécher) — Good evening

- Лека нощ (léka nósht) — Good night

- Довиждане (dovízhdane) — Good-bye

- Чао (chao) (informal) - Bye

- Как си? (kák si) (informal) — How are you?

- Как сте? (kák sté) (formal, and also plural form) - How are you?

- Да (dá) - Yes

- Не (né) - No

- Може би (mózhé bí) - Maybe

- Какво правиш? (kakvó právish) (informal) — What are you doing?

- Какво правите? (kakvó právite) (formal, and also plural form) - What are you doing?

- Добре съм (dobré səm) — I’m fine

- Всичко най-хубаво (vsíchko nai-húbavo) — All the best

- Поздрави (pózdravi) — Regards

- Благодаря (blagodaryə́) (formal and informal) — Thank you

- Мерси (mersi) (informal) - Thank you

- Моля (mólia) — Please

- Моля (mólia) — You're welcome

- Извинете! (izvinéte) (formal) — Excuse me!

- Извинявай! (izviniávai) (informal) — Sorry!

- Колко е часът? (kólko e chasə́t) — What’s the time?

- Говорите ли ...? (govórite li...) — Do you speak ...?

- ...английски (anglíski) — English

- ...български (bə́lgarski) — Bulgarian

- ...китайски (kitáiski) — Chinese

- ...френски (frénski) — French

- ...немски (némski) — German

- ...гръцки (grə́tski) — Greek

- ...италиански (italiánski) — Italian

- ...японски (iapónski) — Japanese

- ...корейски (koréiski) — Korean

- ...латински (latínski) — Latin

- ...испански (ispánski) — Spanish

- Ще се видим скоро (shté sé vídim skóro) - We'll see each other soon

- Ще се видим утре (shté sé vídim útre) - We'll see each other tomorrow

See also

- Common phrases in Bulgarian

- Romanization of Bulgarian

- Torlakian dialect

- Swadesh list of Bulgarian words

References

- Comrie, Bernard and Corbett, Greville G. (1993) The Slavonic Languages, London and New York: Routledge ISBN 0-415-04755-2

- International Phonetic Association (1999) Handbook of the International Phonetic Association ISBN 0-521-63751-1

External links

Study Bulgarian

- The Bulgarian Language Online Course — Free Samples — audio — includes Romantic Phrases

- Free online resources for learners

Linguistic reports

Dictionaries

- Bulgarian vocabulary

- Bulgarian-English-Bulgarian Online dictionary from SA Dictionary

- Bulgarian Dictionary: from Webster’s Dictionary

- Online English–Bulgarian machine translation

Dictionaries Software:

a. English-Bulgarian-English

- SA Dictionary - 'the classics'

- AEnglish Dictionary XP - confortable for use, downloads , (although the website is not in english the menues of dictionary are in Enlgish)

Other:

Links conserning topics of this article

Categories: