This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Wendi.gu (talk | contribs) at 17:07, 30 November 2017 (Restructured data table to make it easier to read and access information, removed some redundant information under the chemotherapy section). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:07, 30 November 2017 by Wendi.gu (talk | contribs) (Restructured data table to make it easier to read and access information, removed some redundant information under the chemotherapy section)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Medical condition

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute lymphoid leukemia |

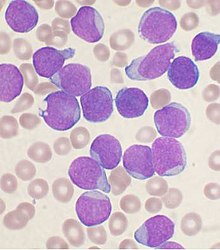

| |

| Bone marrow aspirate smear from a person with precursor B-cell ALL | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

| Symptoms | Fatigue, bone pain, easy bleeding and bruising, infections, enlarged lymph nodes, unexplained fever, weight loss |

| Usual onset | 2-5 years old |

| Diagnostic method | Bone marrow biopsy |

| Frequency | 1 in 1,500 children |

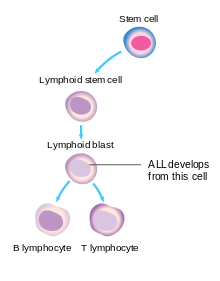

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a cancer of the lymphoid lineage of blood cells, characterized by the overproduction of immature lymphocytes, called lymphoblasts, and their accumulation in the bone marrow. The accumulation of lymphoblasts in the bone marrow interferes with the production of red and white blood cells and platelets, leading to the symptoms of leukemia. These symptoms can include the fatigue and pallor of anemia, increased risk of infection, and easy bleeding and bruising. In addition, the physical crowding of lymphoblasts within the confined space of the bone marrow can lead to arm or leg pain.

ALL is most common in childhood, with a peak incidence at 2-5 years of age and another peak in old age. About 6,000 cases are reported in the United States every year. Internationally, ALL is more common in Caucasians than in Africans; it is more common in Hispanics and in Latin America. Cure is a realistic goal and is achieved in more than 80% of affected children, although only 20–40% of adults are cured. "Acute" is defined by the World Health organization standards, in which greater than 20% of the cells in the bone marrow are blasts. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is defined as having less than 20% blasts in the bone marrow.

Signs and symptoms

Initial symptoms on presentation can be nonspecific, particularly in children. In a meta-analysis, over 50% of children with leukemia had one or more of these five features on clinical presentation: palpable liver (64%), palpable spleen (61%), pallor (54%), fever (53%), and bruising (52%). Additionally, recurrent infections, fatigue, limb pain, and lymphadenopathy can be prominent features of leukemia. These symptoms largely reflect the normal and healthy blood cells crowded out by malignant and immature white blood cells (WBC) in the bone marrow. The resulting bone marrow failure causes dysfunctional erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets. The B symptoms, such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss, are often present as well. While WBC count at initial presentation can vary, circulating lymphoblasts are generally seen on peripheral smears. Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms extending from cranial neuropathies to meningeal infiltration can be identified in <10% of adults and <5% of children with ALL, particularly mature B-cell ALL (Burkitt leukemia) at presentation.

While many presenting symptoms can be found in self-limited childhood illness, persistent or unexplained common signs should be worked up for malignancy. Laboratory tests that might show abnormalities include blood count tests, renal function tests, electrolyte tests, and liver enzyme tests.

The signs and symptoms of ALL are variable but follow from bone marrow replacement and/or organ infiltration. Below include

- Generalized weakness and fatigue

- Anemia

- Dizziness

- Headache, vomiting, lethargy, nuchal rigidity, or cranial nerve palsies (CNS involvement)

- Frequent or unexplained fever and infection

- Weight loss and/or loss of appetite

- Excessive and unexplained bruising

- Bone pain, joint pain (caused by the spread of "blast" cells to the surface of the bone or into the joint from the marrow cavity)

- Breathlessness

- Enlarged lymph nodes, liver and/or spleen

- Pitting edema (swelling) in the lower limbs and/or abdomen

- Petechiae, which are tiny red spots or lines in the skin due to low platelet levels

- Testicular enlargement

- Mediastinal mass

Cause

Functional germline mutations of some cancer-related genes have been found in familial ALL or enriched in radic cases (e.g., PAX5, ETV6 and CDKN2A), accounting for ALL susceptibility for a small proportion of people, while large genome wide association studies revealed multiple inherited predisposition to ALL risk, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at ARID5B, IKZF1, CEBPE, PIP4K2A, GATA3, and CDKN2A loci among diverse populations.

Epidemiological studies suggest that environmental factors on their own make only a minor contribution to disease risk, but environmental factors may interact with genetics. Genome-wide association studies have found associations with a number of genetic single-nucleotide polymorphisms, including ARID5B, IKZF1 and CEBPE.

There is an increased incidence in people with Down syndrome, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, X-linked agammaglobulinemia, severe combined immunodeficiency, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Kostmann syndrome, Neurofibromatosis type 1, Ataxia-telangiectasia, Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. There is an increased risk in people with a family history of autoimmune diseases, particularly autoimmune thyroid diseases (namely Graves' disease or Hashimoto's thyroiditis).

Pathophysiology

In general, cancer is caused by damage to DNA that leads to uncontrolled cellular growth and spreads throughout the body, either by increasing chemical signals that cause growth or by interrupting chemical signals that control growth. Damage can be caused through the formation of fusion genes, as well as the dysregulation of a proto-oncogene via juxtaposition of it to the promoter of another gene, e.g. the T-cell receptor gene. This damage may be caused by environmental factors such as chemicals, drugs or radiation, and occurs naturally during mitosis or other normal processes (although cells have numerous mechanisms of DNA repair that help to reduce this).

ALL is associated with exposure to radiation and chemicals in animals and humans. High level radiation exposure is a known risk factor for developing leukemia, as found by studies of survivors of atom bomb exposure in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In animals, exposure to benzene and other chemicals can cause leukemia. Epidemiological studies have associated leukemia with workplace exposure to chemicals, but these studies are not as conclusive. Some evidence suggests that secondary leukemia can develop in individuals treated for other cancers with radiation and chemotherapy as a result of that treatment.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing ALL begins with a medical history, physical examination, complete blood count, and blood smears. Because the symptoms are so general, many other diseases with similar symptoms must be excluded. Typically, the higher the white blood cell count, especially if the number of cancerous malignant abnormal blast cells are also high, the worse the prognosis. Blast cells are seen on blood smear in the majority of cases (blast cells are precursors — stem cells — to all immune cell lines). A bone marrow biopsy provides conclusive proof of ALL. A lumbar puncture (also known as a spinal tap) will indicate whether the spinal column and brain have been invaded.

Pathological examination, cytogenetics (in particular the presence of Philadelphia chromosome), and immunophenotyping establish whether myeloblastic (neutrophils, eosinophils, or basophils) or lymphoblastic (B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes) cells are the problem. RNA testing can establish how aggressive the disease is; different mutations have been associated with shorter or longer survival. Immunohistochemical testing may reveal TdT or CALLA antigens on the surface of leukemic cells. TdT is a protein expressed early in the development of pre-T and pre-B cells, whereas CALLA is an antigen found in 80% of ALL cases and also in the "blast crisis" of CML.

Medical imaging (such as ultrasound or CT scanning) can find invasion of other organs commonly the lung, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, brain, kidneys, and reproductive organs.

-

acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), peripheral blood of a child, Pappenheim stain, magnification x100

acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), peripheral blood of a child, Pappenheim stain, magnification x100

-

bone marrow smear (large magnification) from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

bone marrow smear (large magnification) from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

-

bone marrow smear from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

bone marrow smear from a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Cytogenetics

Cytogenetic translocations associated with specific molecular genetic abnormalities in ALL

| Cytogenetic translocation | Molecular genetic abnormality | % |

|---|---|---|

| cryptic t(12;21) | TEL–AML1 fusion | 25.4% |

| t(1;19)(q23;p13) | E2A–PBX (PBX1) fusion | 4.8% |

| t(9;22)(q34;q11) | BCR-ABL fusion(P185) | 1.6% |

| t(4;11)(q21;q23) | MLL–AF4 fusion | 1.6% |

| t(8;14)(q24;q32) | IGH-MYC fusion | |

| t(11;14)(p13;q11) | TCR–RBTN2 fusion |

12;21 is the most common translocation and portends a good prognosis. 4;11 is the most common in children under 12 months and portends a poor prognosis.

Classification

As ALL is not a solid tumor, the TNM notation, used in solid cancers, has no relevance. Lymphoblastic lymphoma is a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a result of abnormal adaptive immune cells, typically T-cells. It usually occurs in children.

Prior to 2008, subtyping of all acute leukemias (including acute myelogenous leukemia, AML) used the French-American-British (FAB) classification, in which ALL was classified as:

- ALL-L1: small uniform cells

- ALL-L2: large varied cells

- ALL-L3: large varied cells with vacuoles (bubble-like features).

The FAB scheme had only a limited impact on treatment choice. In 2008, the World Health Organization scheme identified three therapeutically distinct categories. These are identified by immunophenotyping of surface markers of the abnormal lymphocytes:

- B-lymphoblastic ALL (this category can be subdivided according to the correlation of the ALL cell immunophenotype with the stages of normal B-cell development)

- Burkitt ALL (corresponds to ALL-L3)

- T-cell ALL.

This subtyping helps determine the prognosis and the most appropriate treatment in treating ALL. It is substantially amplified by cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics tests.

- 1. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Synonyms: Former FAB L1/L2

- i. Precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Cytogenetic subtypes:

- t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), BCR-ABL1

- t(v;11q23), MLL rearranged

- t(12;21)(p13;q22), TEL-AML1 (ETV6-RUNX1)

- t(1;19)(q23;p13.3), TCF3-PBX1

- t(5;14)(q31;q32), IL3-IGH

- hyperdiploidy

- hypodiploidy

- ii. Precursor T acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma

- i. Precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Cytogenetic subtypes:

- 2. Burkitt's leukemia/lymphoma. Synonyms: Former FAB L3

- 3. Biphenotypic acute leukemia

Variant features

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with cytoplasmic granules

- Aplastic presentation of ALL

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia with eosinophilia

- Relapse of lymphoblastic leukemia

- Secondary ALL

Immunophenotyping

The use of a TdT assay and a panel of monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) to T cell and B cell associated antigens will identify almost all cases of ALL.

Immunophenotypic categories of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL):

| Types | FAB Class | Tdt | T cell associate antigen | B cell associate antigen | c Ig | s Ig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor B | L1,L2 | + | − | + | −/+ | − |

| Precursor T | L1,L2 | + | + | − | − | − |

| B-cell | L3 | − | − | + | − | + |

Treatment

The earlier ALL is detected, the more effective the treatment. The aim is to induce a lasting remission, defined as the absence of detectable cancer cells in the body (usually less than 5% blast cells in the bone marrow).

Treatment for acute leukemia can include chemotherapy, steroids, radiation therapy, intensive combined treatments (including bone marrow or stem cell transplants), and growth factors.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the initial treatment of choice. Most ALL patients will receive a combination of medications. There are no surgical options because of the body-wide distribution of the malignant cells. In general, cytotoxic chemotherapy for ALL combines multiple antileukemic drugs tailored to each patient. Chemotherapy for ALL consists of three phases: remission induction, intensification, and maintenance therapy.

| Phase | Description | Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Remission induction | Aim to:

*Due to presence of CNS involvement in 10–40% of adult patients at diagnosis, start Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis and treatment and continue during the consolidation/intensification period.

|

Combination of:

Central nervous system prophylaxis can be achieved via :

In Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL, the intensity of initial induction treatment may be less than has been traditionally given. |

| Consolidation/intensification |

|

Typical protocols use the following given as blocks in different combinations:

Central nervous system relapse is treated with intrathecal administration of hydrocortisone, methotrexate, and cytarabine. |

| Maintenance therapy |

|

Typical protocol would include:

|

As the chemotherapy regimens can be intensive and protracted, many patients have an intravenous catheter inserted into a large vein (termed a central venous catheter or a Hickman line), or a Portacath, usually placed near the collar bone, for lower infection risks and the long-term viability of the device.

Males usually have a longer course of treatment than females as the testicles can act as a reservoir for the cancer.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy (or radiotherapy) is used on painful bony areas, in high disease burdens, or as part of the preparations for a bone marrow transplant (total body irradiation). Radiation in the form of whole-brain radiation is also used for central nervous system prophylaxis, to prevent recurrence of leukemia in the brain. Whole-brain prophylaxis radiation used to be a common method in treatment of children’s ALL. Recent studies showed that CNS chemotherapy provided results as favorable but with less developmental side-effects. As a result, the use of whole-brain radiation has been more limited. Most specialists in adult leukemia have abandoned the use of radiation therapy for CNS prophylaxis, instead using intrathecal chemotherapy.

Biological therapy

For some subtypes of relapsed ALL, aiming at biological targets such as the proteasome, in combination with chemotherapy, has given promising results in clinical trials. Selection of biological targets on the basis of their combinatorial effects on the leukemic lymphoblasts can lead to clinical trials for improvement in the effects of ALL treatment.

In ongoing clinical trials, a CD19-CD3 bi-specific monoclonal murine antibody, blinatumomab, is showing great promise.

Immunotherapy

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) have been developed as a promising immunotherapy for ALL. This technology uses a single chain variable fragment (scFv) designed to recognize the cell surface marker CD19 as a method of treating ALL.

CD19 is a molecule found on all B-cells and can be used as a means of distinguishing the potentially malignant B-cell population. In this therapy, mice are immunized with the CD19 antigen and produce anti-CD19 antibodies. Hybridomas developed from mouse spleen cells fused to a myeloma cell line can be developed as a source for the cDNA encoding the CD19 specific antibody. The cDNA is sequenced and the sequence encoding the variable heavy and variable light chains of these antibodies are cloned together using a small peptide linker. This resulting sequence encodes the scFv. This can be cloned into a transgene, encoding what will become the endodomain of the CAR. Varying arrangements of subunits serve as the endodomain, but they generally consist of the hinge region that attaches to the scFv, a transmembrane region, the intracellular region of a costimulatory molecule such as CD28, and the intracellular domain of CD3-zeta containing ITAM repeats. Other sequences frequently included are: 4-1bb and OX40. The final transgene sequence, containing the scFv and endodomain sequences is then inserted into immune effector cells that are obtained from the patient and expanded in vitro. In trials these have been a type of T-cell capable of cytotoxicity.

Inserting the DNA into the effector cell can be accomplished by several methods. Most commonly, this is done using a lentivirus that encodes the transgene. Pseudotyped, self-inactivating lentiviruses are an effective method for the stable insertion of a desired transgene into the target cell. Other methods include electroporation and transfection, but these are limited in their efficacy as transgene expression diminishes over time.

The gene-modified effector cells are then transplanted back into the patient. Typically this process is done in conjunction with a conditioning regimen such as cyclophosphamide, which has been shown to potentiate the effects of infused T-cells. This effect has been attributed to making an immunologic space within which the cells populate. The process as a whole results in an effector cell, typically a T-cell, that can recognize a tumor cell antigen in a manner that is independent of the major histocompatibility complex and which can initiate a cytotoxic response.

In 2017, a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory panel voted its unanimous positive recommendation of tisagenlecleucel as a CAR-T therapy for acute B-cell lymphoblastic leukaemia patients who did not respond adequately to other treatments or have relapsed. The FDA may or may not follow this recommendation. In a 22-day process, the "drug" is customized for each patient. T cells cells purified from each patient are modified by a virus that inserts genes that encode a chimaeric antigen receptor into their DNA, one that recognizes leukaemia cells.

Pregnancy

Leukemia is rarely associated with pregnancy, affecting only about 1 in 10,000 pregnant women. How it is handled depends primarily on the type of leukemia. Acute leukemias normally require prompt, aggressive treatment, despite significant risks of pregnancy loss and birth defects, especially if chemotherapy is given during the developmentally sensitive first trimester.

It is possible, although extremely rare, for leukemia to spread from the mother to the child. This is called vertical transmission.

Gene therapy

Tisagenlecleucel is a type of gene therapy used for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia that has failed usual treatment. In August 2017, it became the first FDA-approved gene therapy in the United States. The medication requires customization to the person.

Prognosis

The five-year survival rate for children who have ALL has improved from zero, six decades ago, to 85% currently, largely because of clinical trials on new chemotherapeutic agents and improvements in stem cell transplantation (SCT) technology.

Five-year survival rates evaluate older, not current, treatments. New drugs, and matching treatment to the genetic characteristics of the blast cells, may improve those rates. The prognosis for ALL differs among individuals depending on a variety of factors:

- Gender: Females tend to fare better than males.

- Ethnicity: Caucasians are more likely to develop acute leukemia than African-Americans, Asians, or Hispanics. However, they also tend to have a better prognosis than non-Caucasians.

- Age at diagnosis: children 1–10 years of age are most likely to develop ALL and to be cured of it. Cases in older patients are more likely to result from chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., the Philadelphia chromosome) that make treatment more difficult and prognoses poorer.

- White blood cell count at diagnosis of less than 50,000/µl

- Cancer spread into the Central nervous system (brain or spinal cord) has worse outcomes.

- Morphological, immunological, and genetic subtypes

- Patient's response to initial treatment

- Genetic disorders such as Down syndrome

Cytogenetics, the study of characteristic large changes in the chromosomes of cancer cells, is an important predictor of outcome.

Some cytogenetic subtypes have a worse prognosis than others. These include:

- A translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, known as the Philadelphia chromosome, occurs in about 20% of adult and 5% in pediatric cases of ALL.

- A translocation between chromosomes 4 and 11 occurs in about 4% of cases and is most common in infants under 12 months.

- Not all translocations of chromosomes carry a poorer prognosis. Some translocations are relatively favorable. For example, hyperdiploidy (>50 chromosomes) is a good prognostic factor.

- Genome-wide copy number changes can be assessed by conventional cytogenetics or virtual karyotyping. SNP array virtual karyotyping can detect copy number changes and LOH status, while arrayCGH can detect only copy number changes. Copy neutral LOH (acquired uniparental disomy) has been reported at key loci in ALL, such as CDKN2A gene, which have prognostic significance. SNP arrayvirtual karyotyping can readily detect copy neutral LOH. Array CGH, FISH, and conventional cytogenetics cannot detect copy neutral LOH.

| Cytogenetic change | Risk category |

|---|---|

| Philadelphia chromosome | Poor prognosis |

| t(4;11)(q21;q23) | Poor prognosis |

| t(8;14)(q24.1;q32) | Poor prognosis |

| Complex karyotype (more than four abnormalities) | Poor prognosis |

| Low hypodiploidy or near triploidy | Poor prognosis |

| High hyperdiploidy (specifically, trisomy 4, 10, 17) | Good prognosis |

| del(9p) | Good prognosis |

| Prognosis | Cytogenetic findings |

|---|---|

| Favorable | Hyperdiploidy > 50 ; t (12;21) |

| Intermediate | Hyperdiploidy 47–50; Normal(diploidy); del (6q); Rearrangements of 8q24 |

| Unfavorable | Hypodiploidy-near haploidy; Near tetraploidy; del (17p); t (9;22); t (11q23) |

| Factor | Unfavorable | Favourable |

|---|---|---|

| Age | <2 or >10 years | 3–5 years |

| Sex | Male | Female |

| Race | Black | Caucasian |

| Organomegally | Present | Absent |

| Mediastinal mass | Present | Absent |

| CVS involvement | Present | Absent |

| Leukocyte count | >50,000mm | <50,000mm |

| Cell type | Non Lymphoid | Lymphoid |

| Cell lineage | Pre B cell + | Early Pre B cell |

| Karyotype | Translocation | Hyperdiploidy |

| Response to treatment | Slow | Rapid |

| Hemogblobin concentration | >10g/dl | <10g/dl |

Unclassified ALL is considered to have an intermediate prognosis.

Epidemiology

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is seen in both children and adults; the highest incidence is seen between ages two and five years. ALL is the most common childhood cancer constituting about 23 to 30% of cancers before age 15. Although 80 to 90% of children will have a durable complete response with treatment it is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among children. In adults, ALL is less common than acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). However, as there are more adults than children, the number of cases of ALL seen in adults is comparable to that seen in children. Its incidence has been estimated to be 1 in 1500 children.

Internationally, ALL is more common in children with Caucasian descent, being more common in Hispanics and in Latin America than in Africa.

United States

In the United States, the annual incidence of ALL is roughly 6,000 3,000–3,500, or approximately one in 50,000. ALL is slightly more common in males than females. In the United States in 2010, incidence from birth to age 19 was 38.4 per 1,000,000 per year in boys and 30.2 per 1,000,000 per year in girls. Prevalence was 30,171, and observed survival was 90% (based on data from 2003–2009). ALL has a bimodal age distribution, having a high incidence in ages 2–5 and another peak in incidence above 50 years old.

United Kingdom

ALL accounts for 8% of all leukemia cases in the United Kingdom; around 650 people were diagnosed with the disease in 2011.

References

- ^ Inaba H, Greaves M, Mullighan CG (June 2013). "Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia" (PDF). Lancet. 381 (9881): 1943–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62187-4. PMC 3816716. PMID 23523389. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Baljevic, Muhamed; Jabbour, Elias; O'Brien, Susan; Kantarjian, Hagop M (2016). "Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". In Kantarjian, HM; Wolff, RA (eds.). The MD Anderson Manual of Medical Oncology (3 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ Boer, JM; den Boer, ML (11 July 2017). "BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: From bench to bedside". European Journal of Cancer. 82: 203–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.012. PMID 28709134.

- ^ Seiter, K (5 February 2014). Sarkodee-Adoo, C; Talavera, F; Sacher, RA; Besa, EC (eds.). "Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Bain, Barbara J. (2017). Leukaemia diagnosis (Fifth ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. p. 251. ISBN 9781119210542. OCLC 965446693.

- ^ Greer, J. P.; Arber, D. A.; Glader, B.; et al. (2013). Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology (13th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-7268-3.

- ^ K. Y. Urayama; A. Manabe (2014). "Genomic evaluations of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia susceptibility across race/ethnicities". Rinsho Ketsueki. 55 (10): 2242–8. PMID 25297793.

- Clarke, Rachel T.; Bruel, Ann Van den; Bankhead, Clare; Mitchell, Christopher D.; Phillips, Bob; Thompson, Matthew J. (1 October 2016). "Clinical presentation of childhood leukaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 101 (10): 894–901. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-311251. ISSN 0003-9888. PMID 27647842.

- Baljevic, Muhamed; Jabbour, Elias; O'Brien, Susan; Kantarjian, Hagop (2016). Accessed November 29, 2017 The MD Anderson Manual of MEdical Oncology. New York, New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0071847944.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - Cortes, J. (February 2001). "Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 15 (1): 145–162. ISSN 0889-8588. PMID 11253605.

- Bleyer, W. A. (August 1988). "Central nervous system leukemia". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 35 (4): 789–814. ISSN 0031-3955. PMID 3047654.

- Ingram, L. C.; Fairclough, D. L.; Furman, W. L.; Sandlund, J. T.; Kun, L. E.; Rivera, G. K.; Pui, C. H. (1 May 1991). "Cranial nerve palsy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma". Cancer. 67 (9): 2262–2268. ISSN 0008-543X. PMID 2013032.

- Xu, H; Zhang, H; Yang, W; Yadav, R; Morrison, AC; et al. (24 June 2015). "Inherited coding variants at the CDKN2A locus influence susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children". Nature Communications. 6: 7553. doi:10.1038/ncomms8553. PMC 4544058. PMID 26104880.

- Shah, S; Schrader, KA; Waanders, E; Timms, AE; Vijai, J; et al. (October 2013). "A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Nature Genetics. 45 (10): 1226–31. doi:10.1038/ng.2754. PMC 3919799. PMID 24013638.

- Noetzli, L; Lo, RW; Lee-Sherick, AB; Callaghan, M; Noris, P; et al. (May 2015). "Germline mutations in ETV6 are associated with thrombocytopenia, red cell macrocytosis and predisposition to lymphoblastic leukemia". Nature Genetics. 47 (5): 535–8. doi:10.1038/ng.3253. PMC 4631613. PMID 25807284.

- Moriyama, T; Metzger, ML; Wu, G; Nishii, R; Qian, M; et al. (December 2015). "Germline genetic variation in ETV6 and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a systematic genetic study". The Lancet. Oncology. 16 (16): 1659–66. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00369-1. PMC 4684709. PMID 26522332.

- Xu, H; Yang, W; Perez-Andreu, V; Devidas, M; Fan, Y; et al. (15 May 2013). "Novel susceptibility variants at 10p12.31-12.2 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in ethnically diverse populations". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 105 (10): 733–42. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt042. PMC 3691938. PMID 23512250.

- Perez-Andreu, V; Roberts, KG; Harvey, RC; Yang, W; Cheng, C; et al. (December 2013). "Inherited GATA3 variants are associated with Ph-like childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and risk of relapse". Nature Genetics. 45 (12): 1494–8. doi:10.1038/ng.2803. PMC 4039076. PMID 24141364.

- Sherborne, AL; Hosking, FJ; Prasad, RB; Kumar, R; Koehler, R; et al. (June 2010). "Variation in CDKN2A at 9p21.3 influences childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia risk". Nature Genetics. 42 (6): 492–4. doi:10.1038/ng.585. PMC 3434228. PMID 20453839.

- Treviño, LR; Yang, W; French, D; Hunger, SP; Carroll, WL; et al. (September 2009). "Germline genomic variants associated with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Nature Genetics. 41 (9): 1001–5. doi:10.1038/ng.432. PMC 2762391. PMID 19684603.

- Papaemmanuil, E; Hosking, FJ; Vijayakrishnan, J; Price, A; Olver, B; et al. (September 2009). "Loci on 7p12.2, 10q21.2 and 14q11.2 are associated with risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Nature Genetics. 41 (9): 1006–10. doi:10.1038/ng.430. PMID 19684604.

- Evans TJ, Milne E, Anderson D, et al. (2014). "Confirmation of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia variants, ARID5B and IKZF1, and interaction with parental environmental exposures". PLoS ONE. 9 (10): e110255. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110255. PMC 4195717. PMID 25310577.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Orkin, S. H.; Nathan, D. G.; Ginsburg, D.; et al. (2014). Nathan and Oski's Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood (8th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4557-5414-4.

- ^ Guo LM, Xi JS, Ma Y, et al. (2014). "ARID5B gene rs10821936 polymorphism is associated with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis based on 39,116 subjects". Tumour Biol. 35 (1): 709–13. doi:10.1007/s13277-013-1097-0. PMID 23975371.

- Brisson GD, Alves LR, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS (2015). "Genetic susceptibility in childhood acute leukaemias: a systematic review". Ecancermedicalscience. 9: 539. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2015.539. PMC 4448992. PMID 26045716.

- Rudant J, Orsi L, Bonaventure A, et al. (2015). "ARID5B, IKZF1 and non-genetic factors in the etiology of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the ESCALE study". PLoS ONE. 10 (3): e0121348. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121348. PMC 4373901. PMID 25806972.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Hsu LI, Chokkalingam AP, Briggs FB, et al. (2015). "Association of genetic variation in IKZF1, ARID5B, and CEBPE and surrogates for early-life infections with the risk of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Hispanic children". Cancer Causes Control. 26 (4): 609–19. doi:10.1007/s10552-015-0550-3. PMC 4504234. PMID 25761407.

- Kliegman, Robert (2016). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier. pp. 2437–2445. ISBN 978-1-4557-7566-8.

- F. Perillat-Menegaux; J. Clavel; M. F. Auclerc; Staff (2003). "Family History of Autoimmune Thyroid Disease and Childhood Acute Leukemia". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 12 (1): 60–3. PMID 12540505. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

A statistically significant association between a history of autoimmune disease in first- or second-degree relatives and ALL (OR, 1.7; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.0–2.8) was found. A relationship between thyroid diseases overall and ALL...was observed. This association was more pronounced for potentially autoimmune thyroid diseases (Grave's disease and/or hyperthyroidism and Hashimoto's disease and/or hypothyroidism) (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.1–10.7 and OR, 5.6; 95% CI, 1.0–31.1, respectively for ALL and ANLL), whereas it was not statistically significant for the other thyroid diseases...The results suggest that a familial history of autoimmune thyroid disease may be associated with childhood acute leukemia.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Leukemia--Acute Lymphocytic". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Preston, D. L.; Kusumi, S.; Tomonaga, M.; Izumi, S.; Ron, E.; Kuramoto, A.; Kamada, N.; Dohy, H.; Matsuo, T. (1 February 1994). "Cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors. Part III. Leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, 1950–1987". Radiation Research. 137 (2 Suppl): S68–97. ISSN 0033-7587. PMID 8127953. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Smith MA, Rubinstein L, Anderson JR, et al. (February 1999). "Secondary Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndrome After Treatment With Epipodophyllotoxins". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 17 (2). American Society for Clinical Oncology: 569–77. PMID 10080601. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Collier, J.A.B (1991). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties, Third Edition. Oxford. p. 810. ISBN 0-19-262116-5.

- Longo, D (2011). "Chapter 110: Malignancies of Lymphoid Cells". Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- Rytting, ME, ed. (November 2013). "Acute Leukemia". Merck Manual Professional. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Stams WA, den Boer ML, Beverloo HB, Meijerink JP, van Wering ER, Janka-Schaub GE, Pieters R (April 2005). "Expression levels of TEL, AML1, and the fusion products TEL-AML1 and AML1-TEL versus drug sensitivity and clinical outcome in t(12;21)-positive pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Clin. Cancer Res. 11 (8): 2974–80. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1829. PMID 15837750.

- ^ Pakakasama S, Kajanachumpol S, Kanjanapongkul S, et al. (August 2008). "Simple multiplex RT-PCR for identifying common fusion transcripts in childhood acute leukemia". Int J Lab Hematol. 30 (4): 286–91. doi:10.1111/j.1751-553X.2007.00954.x. PMID 18665825.

- McWhirter JR, Neuteboom ST, Wancewicz EV, et al. (September 1999). "Oncogenic homeodomain transcription factor E2A-Pbx1 activates a novel WNT gene in pre-B acute lymphoblastoid leukemia". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (20): 11464–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.20.11464. PMC 18056. PMID 10500199.

- Rudolph C, Hegazy AN, von Neuhoff N, et al. (August 2005). "Cytogenetic characterization of a BCR-ABL transduced mouse cell line". Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 161 (1): 51–6. doi:10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.12.021. PMID 16080957.

- Caslini C, Serna A, Rossi V, et al. (June 2004). "Modulation of cell cycle by graded expression of MLL-AF4 fusion oncoprotein". Leukemia. 18 (6): 1064–71. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2403321. PMID 14990976.

- Martín-Subero JI, Odero MD, Hernandez R, Cigudosa JC, Agirre X, Saez B, Sanz-García E, Ardanaz MT, Novo FJ, Gascoyne RD, Calasanz MJ, Siebert R (August 2005). "Amplification of IGH/MYC fusion in clinically aggressive IGH/BCL2-positive germinal center B-cell lymphomas". Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 43 (4): 414–23. doi:10.1002/gcc.20187. PMID 15852472.

- Zalcberg IQ, Silva ML, Abdelhay E, et al. (October 1995). "Translocation 11;14 in three children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia of T-cell origin". Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 84 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1016/0165-4608(95)00062-3. PMID 7497440.

- "ACS :: How Is Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia Classified?". Archived from the original on 23 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ DeAngelo DJ, Pui C. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia and lymphoblastic lymphoma. Chapter 19 of American Society of Hematology Self-Assessment Program. 2013. ISBN 9780982843512

- "Advances in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | Clinical Laboratory Science | Find Articles at BNET.com". Clinical Laboratory Science. 2004.

- K. Seiter; J. E. Harris (8 September 2016). "Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Staging: Classification for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia". Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017 – via eMedicine.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) Information – Mount Sinai – New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Jabbour E, Thomas D, Cortes J, et al. (15 May 2010). "Central nervous system prophylaxis in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: current and emerging therapies". Cancer. 116 (10): 2290–300. doi:10.1002/cncr.25008. PMID 20209620.

- M. Yanada (2015). "Time to tune the treatment of Ph+ ALL". Blood. 125 (24): 3674–5. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-641704. PMID 26069331.

- Seiter K, Harris JE. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment Protocols. emedicine; Medscape. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 September 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Hoffbrand, Victor; Moss, Paul; Pettit, John (31 October 2006). Essential Haematology. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-3649-5. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Messinger YH, Gaynon PS, Sposto R, et al. (July 2012). "Bortezomib with chemotherapy is highly active in advanced B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Therapeutic Advances in Childhood Leukemia & Lymphoma (TACL) Study". Blood. 120 (2): 285–90. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-04-418640. PMID 22653976. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Lambrou GI, Papadimitriou L, Chrousos GP, Vlahopoulos SA (January 2012). "Glucocorticoid and proteasome inhibitor impact on the leukemic lymphoblast: multiple, diverse signals converging on a few key downstream regulators". Mol Cell Endocrinol. 351 (2): 142–51. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.003. PMID 22273806.

- Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, et al. (2013). "Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia". N. Engl. J. Med. 368 (16): 1509–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. PMC 4058440. PMID 23527958.

- ^ Barrett DM, Singh N, Porter DL, et al. (2014). "Chimeric antigen receptor therapy for cancer". Annu. Rev. Med. 65: 333–47. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060512-150254. PMC 4120077. PMID 24274181.

- Alonso-Camino V, Sánchez-Martín D, Compte M, et al. (2013). "CARbodies: Human Antibodies Against Cell Surface Tumor Antigens Selected From Repertoires Displayed on T Cell Chimeric Antigen Receptors". Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2: e93. doi:10.1038/mtna.2013.19. PMC 4817937. PMID 23695536.

- Zufferey R, Dull T, Mandel RJ, et al. (1998). "Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery". J. Virol. 72 (12): 9873–80. PMC 110499. PMID 9811723.

- Ledford, Heidi (12 July 2017). "Engineered cell therapy for cancer gets thumbs up from FDA advisers". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22304.

- ^ Shapira T, Pereg D, Lishner M (September 2008). "How I treat acute and chronic leukemia in pregnancy". Blood Rev. 22 (5): 247–59. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2008.03.006. PMID 18472198.

- Isoda T, Ford AM, Tomizawa D, et al. (October 2009). "Immunologically silent cancer clone transmission from mother to offspring". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (42): 17882–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904658106. PMC 2764945. PMID 19822752.

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements—FDA approval brings first gene therapy to the United States". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Park KD (March 2014). "How do we prepare ourselves for a new paradigm of medicine to advance the treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia?". Blood Research. 49 (1): 3–4. doi:10.5045/br.2014.49.1.3. PMC 3974954. PMID 24724058.

- Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, et al. (15 April 2007). "Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial". Blood. 109 (8): 3189–3197. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. PMID 17170120.

- Kawamata N, Ogawa S, Zimmermann M, Kato M, Sanada M, Hemminki K, Yamatomo G, Nannya Y, Koehler R, Flohr T, Miller CW, Harbott J, Ludwig WD, Stanulla M, Schrappe M, Bartram CR, Koeffler HP (15 January 2008). "Molecular allelokaryotyping of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias by high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism oligonucleotide genomic microarray". Blood. 111 (2): 776–784. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-05-088310. PMC 2200831. PMID 17890455.

- Bungaro S, Dell'Orto MC, Zangrando A, et al. (1 January 2009). "Integration of genomic and gene expression data of childhood ALL without known aberrations identifies subgroups with specific genetic hallmarks". Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer. 48 (1): 22–38. doi:10.1002/gcc.20616. PMID 18803328.

- Sulong S, Moorman AV, Irving JA, et al. (1 January 2009). "A comprehensive analysis of the CDKN2A gene in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals genomic deletion, copy number neutral loss of heterozygosity, and association with specific cytogenetic subgroups". Blood. 113 (1): 100–107. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-166801. PMID 18838613.

- Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics By Karen Marcdante, Robert M. Kliegman, Richard E. Behrman, Hal B. Jenson p597

- The Guide Paediatrics. ISBN 978-978-917-9909. p51

- Den Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, et al. (January 2009). "A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genome-wide classification study". Lancet Oncol. 10 (2): 125–34. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70339-5. PMC 2707020. PMID 19138562.

- Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A (March–April 2014). "Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 64 (2): 83–103. doi:10.3322/caac.21219. PMID 24488779.

- "Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Template:Arthritis in children

| Leukaemias, lymphomas and related disease | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||