This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Green Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairperson | Tom A. Wood |

| Co-Chairperson | Paul Ekins |

| Founded | June 1985 (June 1985) |

| Dissolved | 1990 |

| Preceded by | The Ecology Party |

| Succeeded by | Green Party of England and Wales Green Party Northern Ireland Scottish Greens |

| Headquarters | London |

| Ideology | Green politics |

| Colours | Green |

The Green Party, also known as the Green Party UK, was a Green political party in the United Kingdom.

Prior to 1985 it was called the Ecology Party, and before that PEOPLE. In 1990, it separated into three regional political parties within the United Kingdom:

Despite the UK Green Party no longer existing as a unified entity, "Green Party" (singular) is still used colloquially to refer collectively to the three separate parties; for example, in the reporting of opinion polls and election results.

History

PEOPLE, 1972–1975

"PEOPLE" redirects here. For the magazine occasionally stylised in all caps, see People (magazine).The Green Party's origins go back to PEOPLE, a political party founded in Coventry in November 1972. An interview with overpopulation expert Paul R. Ehrlich in Playboy magazine inspired a small group of professional and business people to form the 'Thirteen Club', so named because it first met on 13 September 1972 at the Napton Bridge pub in Napton-on-the-Hill near Daventry. This included surveyors and property agents Freda Sanders and Michael Benfield, and husband-and-wife solicitors Lesley and Tony Whittaker (a former Kenilworth councillor for the Conservative Party), all with practices in Coventry. Out of the original 'club' these four individuals launched 'PEOPLE' as a new political party to challenge the UK political establishment. They called its first public meeting on 22 February 1973 at their office at 69 Hertford Street in Coventry. Its policy concerns published in 1973 included economics, employment, defence, energy and fuel supplies, land tenure, pollution and social security, all set within an ecological perspective. "Zero growth" (or "steady state") economics were a strong feature in the party's philosophical basis.

Later recognised as the first Green party in the United Kingdom and Europe as a whole, the party published the 'Manifesto for Survival' in June 1974, between the two general elections of that year. The manifesto was inspired by A Blueprint for Survival published by The Ecologist magazine. 'A Manifesto for a Sustainable Society' was an expanded statement of policies published in 1975 published under the newly changed name of the Ecology Party. The editor of The Ecologist, Edward 'Teddy' Goldsmith, merged his 'Movement for Survival' with PEOPLE in 1974. Goldsmith became one of the leading members of the new party during the 1970s.

With "Steady State" economics featured in the party's philosophical basis, the all-UK party became a persistent and growing presence in general elections and European elections, often fielding enough candidates to qualify for television and radio election broadcasts.

Membership rose and the party contested both 1974 general elections. In the February 1974 general election, PEOPLE received 4,576 votes in 7 seats. In later years, an influx of left-wing activists took PEOPLE in a more left-wing direction, causing something of a split. In the October 1974 general election, where PEOPLE's average vote fell to just 0.7% much of the difference was made by Liberal candidates entering the fray. After much internal debate the party's 1975 Conference adopted a proposal to change its name to 'The Ecology Party' in order to gain more recognition as the party of environmental concern. This was supported by the Executive, who had found media recognition hard to achieve under the original name. 'Green' was not an appropriate name at that time and 'ecology' had become more publicly recognised as a concept in the party's three years of campaigning.

1975 conference

After much debate, the party's 1975 conference adopted a proposal to change its name to the Ecology Party to gain more recognition as the party of environmental concern.

Party co-founder Tony Whittaker noted in an interview with Derek Wall '… voters did not connect PEOPLE with ecology. What I wanted was something that the media could look up in their files so that, when they wanted a spokesman of the issue of ecology, they could find the Ecology Party and pick up the phone. It was as brutal and basic as that. PEOPLE didn't communicate what we had hoped it would communicate'.

Derek Wall, in his history of the Green Party, contends that the new political movement focused initially on the theme of survival, which shaped the "bleak evolution" of the nascent ecological party during the 1970s. Furthermore, the effect of the "revolution of values" during the 1960s would come later. In Wall's eyes, the party suffered from a lack of media attention and "opposition from many environmentalists", which contrasted the experience of other emerging Green parties, such as Germany's Die Grünen. Nonetheless, PEOPLE invested much of its resources in engaging with the indifferent environmental movement, which Wall calls a "tactical mistake".

The Ecology Party, 1975–1985

The party won its first representation in 1976, when John Luck took a seat on Rother District Council in East Sussex, and party Campaign Secretary John Davenport won a parish council seat in Kempsey.

Jonathan Tyler was elected Chairman of the party in 1976, and Jonathon Porritt became a prominent member. At the 1977 Party Conference in Birmingham, the party's first constitution was ratified and Jonathon Porritt was elected to the Ecology Party National Executive Committee (NEC). Porritt would become the party's most significant public figure, working, with David Fleming, "to provide the Party with an attractive image and effective organisation".

With Porritt gaining increasing prominence and an election manifesto called The Real Alternative, the Ecology Party fielded 53 candidates in the 1979 general election, entitling them to radio and television election broadcasts. Though many considered this a gamble, the plan, encouraged by Porritt, worked, as the party received 39,918 votes (an average of 1.5%) and membership jumped tenfold from around 500 to 5,000 or more. This, Derek Wall notes, meant that the Ecology Party "became the fourth party in UK politics, ahead of the National Front and Socialist Unity".

Following this electoral success, the party introduced Annual Spring Conferences to accompany Autumn Conferences, and a process of building up a large compendium of policies began, culminated in today's Policies for a Sustainable Society (which encompasses around 124 520 words). At the same time, according to Wall, "the Post-1968 generation" began to join the party, advocating non-violent direct action as an important element of the Ecology Party vision outside of electoral politics. This manifested itself in an apparent "decentralist faction" who gained ground within the party, leading to the Party Conference stripping the Executive of powers and rejecting the election of a single leader. The new generation was in evidence in the first 'Summer Green Gathering' in July 1980, the action of the Ecology Party CND (later Green CND), and the Greenham Common camp. The party also became increasingly feminist.

1983 general election

Due to the recession causing the marginalisation of Green issues, Roy Jenkins leaving the Labour Party to form the Social Democratic Party in 1981, and the inability of the Party to absorb the rapid increase in membership, the early-1980s were extremely tough for the Ecology Party. Nonetheless, the Party prepared for the 1983 general election, inspired by the success of Die Grünen in Germany. At the 1983 general election, the Ecology Party stood over 100 candidates and gained 54,299 votes.

Name change and internal strife, 1985–1986

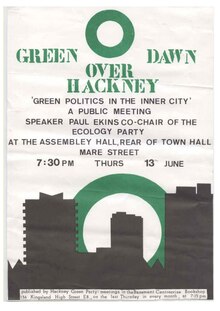

1985 was a time of political change in the UK. After the formation of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), there were noises being made that the UK needed a "green" party. In response to the rumours that a group of Liberal Party activists were about to launch a UK 'Green Party', HELP (the Hackney Local Ecology Party) registered the name The Green Party, with a green circle, designed by Steve O’Brien, as its logo. The first public meeting, chaired by David Fitzpatrick (then an Ecology Party speaker), was 13 June 1985 in Hackney Town Hall. Paul Ekins (then co-chair of the Ecology Party) spoke on the subject of Green politics and the inner city. Hackney Green Party put a formal proposal to the Ecology Party Autumn Conference in Dover that year to change to the Green Party, which was supported by the majority of attendees, including John Abineri, formerly an actor in the BBC series Survivors who supported adding Green to the name to fall in line with other environmental parties in Europe.

The next year, an internal dispute arose within the party. A faction calling itself the Party Organisation Working Group (POWG) proposed constitutional amendments designed to create a streamlined, two-tier structure to govern the internal workings of the party. Decentralists voted these proposals down. Paul Ekins and Jonathan Tyler, prominent party activists and leading members of POWG, then formed a semi-covert group called Maingreen, whose private comments, upon becoming public knowledge, suggested to many that they wished to take control of the party. Tyler and Ekins resigned and left the party but Derek Wall describes how the "wounds" left by the 'Maingreen Affair' lingered on in the heated internal debates of the late 1980s.

1987 general election

Meanwhile, the party gained ground electorally. The 1987 general election saw the 133 Greens standing for office take 89,753 votes (1.3% on average), an improvement on 1983. The next two years would see growing membership and increasing media attention. This coincided with greater concern over the environment following the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and concern over CFCs.

Campaign success, 1989

The party enjoyed further success. Its Campaign for Real Democracy' launched by the party allowed it to play a part in the Anti-Poll Tax Campaign. The party's biggest success came at the 1989 European elections, where the Green Party won 2,292,695 votes and received 15% of the overall vote. European elections in Great Britain were then run on a first-past-the-post basis, whilst the three seats in Northern Ireland were elected by single transferable vote, and the party failed to gain any seats.

According to Derek Wall, the party would have gained 12 seats if they had been running in other European countries who employed Proportional Representation. Wall explains this "breakthrough" as a combination of the declining popularity of Margaret Thatcher, the reaction to the Poll Tax, Conservative opposition to the European Union, ineffective Labour Party and Liberal Democrat campaigns and a well-prepared Green Party campaign. That environmental issues were very prominent in UK politics at the time should also be added to this list. At no time before or since have Green issues been so high on the minds of UK voters as a voting issue.

As a result of this success, Sara Parkin and David Icke rose to prominence in the UK media, soon becoming two of the four Principal Speakers, a position created in lieu of a leader. Parkin especially was in demand as a Green spokesperson. However, the new media attention was not always handled well by the party as a whole. In the run up to the 1989 party conference, it attracted criticism for advocating policies aiming to reduce the total population, proposals which were subsequently rejected. Further controversies included Derek Wall's rejection of possible alliances to establish PR. Icke too attracted criticism soon after writing his second book in 1989, an outline of his views on the environment.

Mainstream political parties were, however, alarmed by the Greens' electoral performance and adopted some 'Green policies' in an attempt to counter the threat. In this period, the Green Party had representation in the House of Lords in the person of George MacLeod, Baron MacLeod of Fuinary, who died in 1991. He was the first British Green parliamentarian.

The breakup of the party, 1990

In 1990, the Scottish and Northern Ireland wings of the Green Party in the United Kingdom decided to separate amicably from the party in England and Wales, to form the Scottish Greens and the Green Party Northern Ireland. The Wales Green Party became an autonomous regional party and remained within the new Green Party of England and Wales.

Leadership

Of the Ecology party:

- 1976: Jonathan Tyler

- 1979: Jonathon Porritt

- 1980: Gundula Dorey

- 1982: Jean Lambert, Alec Ponton and Jonathon Porritt

- 1983: Paul Ekins, Jean Lambert and Jonathon Porritt

Of the Green Party:

| Year | Chairs | Principal Speakers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Jo Robins | Heather Swailes | Lindy Williams | Principal Speakers introduced 1987 | |||||

| 1986 | Jean Lambert | Brig Oubridge | |||||||

| 1987 | Janet Alty | Tim Cooper | Linda Hendry | Jean Lambert | Richard Lawson | 3 Principal Speakers in 1987 | |||

| 1988 | Liz Crosbie | Penny Kemp | Lindsay Cooke | David Icke | Sara Parkin | David Spaven | Frank Williamson | ||

| 1989 | Nick Anderson | Caroline Lucas | Jo Steranka | Janet Alty | Liz Crosbie | Steve Rackett | |||

Electoral performance

General elections

| 1974 (Feb.) | 4,576 | 0.015% | 0 / 635 | Hung parliament (Lab. minority government) |

| 1974 (Oct.) | 1,996 | 0.007% | 0 / 635 | Labour victory |

| 1979 | 39,918 | 0.1% | 0 / 635 | Conservative victory |

| 1983 | 54,299 | 0.2% | 0 / 650 | Conservative victory |

| 1987 | 89,753 | 0.3% | 0 / 650 | Conservative victory |

February 1974

The party stood six candidates in the February 1974 General Election. They received a total of 4,576. The party lost all of its deposits by failing to win 12.5% of the votes cast, namely a total of £900 (equivalent to £11,800 in 2023). Lesley Whittaker and Edward Goldsmith were two of the six who stood in the election.

| Constituency | Candidate | Votes | Percentage | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coventry North East | Alan H Pickard | 1,332 | 2.8 | 3 |

| Coventry North West | Lesley Whittaker | 1,542 | 3.9 | 3 |

| Eye | Edward Goldsmith | 395 | 0.7 | 4 |

| Hornchurch | Benjamin Percy-Davies | 619 | 1.3 | 4 |

| Leeds North East | Clive Lord | 300 | 0.7 | 4 |

| Liverpool West Derby | D B Pascoe | 388 | 0.9 | 4 |

October 1974

Membership rose and the party stood five candidates in the October General Election which cost the party £750. This affected preparations for that election, when PEOPLE's average vote fell to just 0.7%.

| Constituency | Candidate | Votes | Percentage | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham Northfield | Elizabeth A Davenport | 359 | 0.7 | 4 |

| Coventry North West | Lesley Whittaker | 313 | 0.8 | 4 |

| Hornchurch | Benjamin Percy-Davies | 797 | 1.8 | 4 |

| Leeds East | Norma Russell | 327 | 0.7 | 4 |

| Romford | L H C Sampson | 200 | 0.5 | 4 |

See also

- History of the Green Party of England and Wales

- Values Party, considered the first national-level environmental party world-wide

Notes

- November 1972 (as PEOPLE); 1975 (as Ecology Party; June 1985 (as Green Party)

- Winning at least 12.5% of votes was required between 1918 and 1985 to obtain a refund of a candidate's deposit.

References

- ^ "Christians in Politics - Guide to the Green Party". christiansinpolitics.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ Haute, Emilie van (28 April 2016). Green Parties in Europe. Routledge. p. 246. ISBN 9781317124542.

- ^ "The Green Party: a short history". The Independent. 23 November 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- "The Green Party: a short history". The Independent. 23 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- Walsh, Peter (22 June 1989). "The humble beginnings of Britain's Green Party". Coventry Evening Telegraph. p. 6.

- British Newspaper Archive (subscription required)

- Encyclopedia of Ecology and Environmental Management. John Wiley & Sons. 15 July 2009. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-4443-1324-6.

- ^ Wall, Derek (1994). Weaving a Bower Against Endless Night: an illustrated history of the UK Green Party . Green Party. ISBN 1-873557-08-6.

- ^ Wall, Derek, Weaving a Bower Against Endless Night: An Illustrated History of the Green Party, 1994

- ^ "Resurgence & Ecologist (Ecologist, Vol 6 No 9 - Nov 1976)". exacteditions.theecologist.org. p. 311. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ECOLOGY - The New Political Force Archived 2011-08-15 at the Wayback Machine", The Ecologist, November 1976, p.311

- "Policy". Youth section of the Green Party of England and Wales: Policy Website. Young Greens. Archived from the original on 10 August 2006. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "Green History UK - Ecology Party in the early 80s - Derek Wall". green-history.uk. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- "HOUSE OF COMMONS PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE FACTSHEET No 22 GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS, 9 JUNE 1983" (PDF). www.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Ecology Party PEB1983 General Election - YouTube". www.youtube.com. 23 October 2018.

- "BBC Politics 97". BBC. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "MORI Polling Trends data". Archived from the original on 5 February 2007.

- "Greens propose 20 million cut in population". The Guardian. 18 September 1989.

- "Parkin is defeated over pre-election pact to achieve PR". The Independent. 25 September 1989.

- Wall, Derek (March 1994). Weaving a Bower Against Endless Night: An Illustrated History of the UK Green Party (published March 1994 to mark the 21st anniversary of the Party). Green Party. ISBN 1-873557-08-6..

- ^ F. W. S. Craig, Minor Parties at British Parliamentary Elections, p.77

External links

- Green Party of England and Wales

- Scottish Green Party

- Green Party in Northern Ireland

- Teddy Goldsmith - Daily Telegraph obituary