| Circle | |

|---|---|

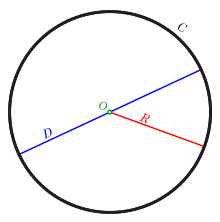

A circle circumference C

diameter D

radius R

centre or origin O A circle circumference C

diameter D

radius R

centre or origin O | |

| Type | Conic section |

| Symmetry group | O(2) |

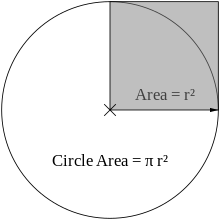

| Area | πR |

| Perimeter | C = 2πR |

A circle is a shape consisting of all points in a plane that are at a given distance from a given point, the centre. The distance between any point of the circle and the centre is called the radius. The length of a line segment connecting two points on the circle and passing through the centre is called the diameter. A circle bounds a region of the plane called a disc.

The circle has been known since before the beginning of recorded history. Natural circles are common, such as the full moon or a slice of round fruit. The circle is the basis for the wheel, which, with related inventions such as gears, makes much of modern machinery possible. In mathematics, the study of the circle has helped inspire the development of geometry, astronomy and calculus.

Terminology

- Annulus: a ring-shaped object, the region bounded by two concentric circles.

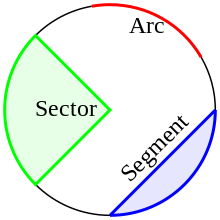

- Arc: any connected part of a circle. Specifying two end points of an arc and a centre allows for two arcs that together make up a full circle.

- Centre: the point equidistant from all points on the circle.

- Chord: a line segment whose endpoints lie on the circle, thus dividing a circle into two segments.

- Circumference: the length of one circuit along the circle, or the distance around the circle.

- Diameter: a line segment whose endpoints lie on the circle and that passes through the centre; or the length of such a line segment. This is the largest distance between any two points on the circle. It is a special case of a chord, namely the longest chord for a given circle, and its length is twice the length of a radius.

- Disc: the region of the plane bounded by a circle. In strict mathematical usage, a circle is only the boundary of the disc (or disk), while in everyday use the term "circle" may also refer to a disc.

- Lens: the region common to (the intersection of) two overlapping discs.

- Radius: a line segment joining the centre of a circle with any single point on the circle itself; or the length of such a segment, which is half (the length of) a diameter. Usually, the radius is denoted and required to be a positive number. A circle with is a degenerate case consisting of a single point.

- Sector: a region bounded by two radii of equal length with a common centre and either of the two possible arcs, determined by this centre and the endpoints of the radii.

- Segment: a region bounded by a chord and one of the arcs connecting the chord's endpoints. The length of the chord imposes a lower boundary on the diameter of possible arcs. Sometimes the term segment is used only for regions not containing the centre of the circle to which their arc belongs.

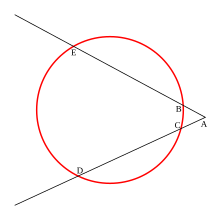

- Secant: an extended chord, a coplanar straight line, intersecting a circle in two points.

- Semicircle: one of the two possible arcs determined by the endpoints of a diameter, taking its midpoint as centre. In non-technical common usage it may mean the interior of the two-dimensional region bounded by a diameter and one of its arcs, that is technically called a half-disc. A half-disc is a special case of a segment, namely the largest one.

- Tangent: a coplanar straight line that has one single point in common with a circle ("touches the circle at this point").

All of the specified regions may be considered as open, that is, not containing their boundaries, or as closed, including their respective boundaries.

|

|

Etymology

The word circle derives from the Greek κίρκος/κύκλος (kirkos/kuklos), itself a metathesis of the Homeric Greek κρίκος (krikos), meaning "hoop" or "ring". The origins of the words circus and circuit are closely related.

History

Prehistoric people made stone circles and timber circles, and circular elements are common in petroglyphs and cave paintings. Disc-shaped prehistoric artifacts include the Nebra sky disc and jade discs called Bi.

The Egyptian Rhind papyrus, dated to 1700 BCE, gives a method to find the area of a circle. The result corresponds to 256/81 (3.16049...) as an approximate value of π.

Book 3 of Euclid's Elements deals with the properties of circles. Euclid's definition of a circle is:

A circle is a plane figure bounded by one curved line, and such that all straight lines drawn from a certain point within it to the bounding line, are equal. The bounding line is called its circumference and the point, its centre.

— Euclid, Book I, Elements

In Plato's Seventh Letter there is a detailed definition and explanation of the circle. Plato explains the perfect circle, and how it is different from any drawing, words, definition or explanation. Early science, particularly geometry and astrology and astronomy, was connected to the divine for most medieval scholars, and many believed that there was something intrinsically "divine" or "perfect" that could be found in circles.

In 1880 CE, Ferdinand von Lindemann proved that π is transcendental, proving that the millennia-old problem of squaring the circle cannot be performed with straightedge and compass.

With the advent of abstract art in the early 20th century, geometric objects became an artistic subject in their own right. Wassily Kandinsky in particular often used circles as an element of his compositions.

Symbolism and religious use

From the time of the earliest known civilisations – such as the Assyrians and ancient Egyptians, those in the Indus Valley and along the Yellow River in China, and the Western civilisations of ancient Greece and Rome during classical Antiquity – the circle has been used directly or indirectly in visual art to convey the artist's message and to express certain ideas. However, differences in worldview (beliefs and culture) had a great impact on artists' perceptions. While some emphasised the circle's perimeter to demonstrate their democratic manifestation, others focused on its centre to symbolise the concept of cosmic unity. In mystical doctrines, the circle mainly symbolises the infinite and cyclical nature of existence, but in religious traditions it represents heavenly bodies and divine spirits.

The circle signifies many sacred and spiritual concepts, including unity, infinity, wholeness, the universe, divinity, balance, stability and perfection, among others. Such concepts have been conveyed in cultures worldwide through the use of symbols, for example, a compass, a halo, the vesica piscis and its derivatives (fish, eye, aureole, mandorla, etc.), the ouroboros, the Dharma wheel, a rainbow, mandalas, rose windows and so forth. Magic circles are part of some traditions of Western esotericism.

Analytic results

Circumference

Main article: CircumferenceThe ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter is π (pi), an irrational constant approximately equal to 3.141592654. The ratio of a circle's circumference to its radius is 2π. Thus the circumference C is related to the radius r and diameter d by:

Area enclosed

As proved by Archimedes, in his Measurement of a Circle, the area enclosed by a circle is equal to that of a triangle whose base has the length of the circle's circumference and whose height equals the circle's radius, which comes to π multiplied by the radius squared:

Equivalently, denoting diameter by d, that is, approximately 79% of the circumscribing square (whose side is of length d).

The circle is the plane curve enclosing the maximum area for a given arc length. This relates the circle to a problem in the calculus of variations, namely the isoperimetric inequality.

Radian

Main article: RadianIf a circle of radius r is centred at the vertex of an angle, and that angle intercepts an arc of the circle with an arc length of s, then the radian measure 𝜃 of the angle is the ratio of the arc length to the radius:

The circular arc is said to subtend the angle, known as the central angle, at the centre of the circle. The angle subtended by a complete circle at its centre is a complete angle, which measures 2π radians, 360 degrees, or one turn.

Using radians, the formula for the arc length s of a circular arc of radius r and subtending a central angle of measure 𝜃 is

and the formula for the area A of a circular sector of radius r and with central angle of measure 𝜃 is

In the special case 𝜃 = 2π, these formulae yield the circumference of a complete circle and area of a complete disc, respectively.

Equations

Cartesian coordinates

Equation of a circle

In an x–y Cartesian coordinate system, the circle with centre coordinates (a, b) and radius r is the set of all points (x, y) such that

This equation, known as the equation of the circle, follows from the Pythagorean theorem applied to any point on the circle: as shown in the adjacent diagram, the radius is the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle whose other sides are of length |x − a| and |y − b|. If the circle is centred at the origin (0, 0), then the equation simplifies to

One coordinate as a function of the other

The circle of radius with center at in the – plane can be broken into two semicircles each of which is the graph of a function, and , respectively: for values of ranging from to .

Parametric form

The equation can be written in parametric form using the trigonometric functions sine and cosine as where t is a parametric variable in the range 0 to 2π, interpreted geometrically as the angle that the ray from (a, b) to (x, y) makes with the positive x axis.

An alternative parametrisation of the circle is

In this parameterisation, the ratio of t to r can be interpreted geometrically as the stereographic projection of the line passing through the centre parallel to the x axis (see Tangent half-angle substitution). However, this parameterisation works only if t is made to range not only through all reals but also to a point at infinity; otherwise, the leftmost point of the circle would be omitted.

3-point form

The equation of the circle determined by three points not on a line is obtained by a conversion of the 3-point form of a circle equation:

Homogeneous form

In homogeneous coordinates, each conic section with the equation of a circle has the form

It can be proven that a conic section is a circle exactly when it contains (when extended to the complex projective plane) the points I(1: i: 0) and J(1: −i: 0). These points are called the circular points at infinity.

Polar coordinates

In polar coordinates, the equation of a circle is

where a is the radius of the circle, are the polar coordinates of a generic point on the circle, and are the polar coordinates of the centre of the circle (i.e., r0 is the distance from the origin to the centre of the circle, and φ is the anticlockwise angle from the positive x axis to the line connecting the origin to the centre of the circle). For a circle centred on the origin, i.e. r0 = 0, this reduces to r = a. When r0 = a, or when the origin lies on the circle, the equation becomes

In the general case, the equation can be solved for r, giving Without the ± sign, the equation would in some cases describe only half a circle.

Complex plane

In the complex plane, a circle with a centre at c and radius r has the equation

In parametric form, this can be written as

The slightly generalised equation

for real p, q and complex g is sometimes called a generalised circle. This becomes the above equation for a circle with , since . Not all generalised circles are actually circles: a generalised circle is either a (true) circle or a line.

Tangent lines

Main article: Tangent lines to circlesThe tangent line through a point P on the circle is perpendicular to the diameter passing through P. If P = (x1, y1) and the circle has centre (a, b) and radius r, then the tangent line is perpendicular to the line from (a, b) to (x1, y1), so it has the form (x1 − a)x + (y1 – b)y = c. Evaluating at (x1, y1) determines the value of c, and the result is that the equation of the tangent is or

If y1 ≠ b, then the slope of this line is

This can also be found using implicit differentiation.

When the centre of the circle is at the origin, then the equation of the tangent line becomes and its slope is

Properties

- The circle is the shape with the largest area for a given length of perimeter (see Isoperimetric inequality).

- The circle is a highly symmetric shape: every line through the centre forms a line of reflection symmetry, and it has rotational symmetry around the centre for every angle. Its symmetry group is the orthogonal group O(2,R). The group of rotations alone is the circle group T.

- All circles are similar.

- A circle circumference and radius are proportional.

- The area enclosed and the square of its radius are proportional.

- The constants of proportionality are 2π and π respectively.

- The circle that is centred at the origin with radius 1 is called the unit circle.

- Thought of as a great circle of the unit sphere, it becomes the Riemannian circle.

- Through any three points, not all on the same line, there lies a unique circle. In Cartesian coordinates, it is possible to give explicit formulae for the coordinates of the centre of the circle and the radius in terms of the coordinates of the three given points. See circumcircle.

Chord

- Chords are equidistant from the centre of a circle if and only if they are equal in length.

- The perpendicular bisector of a chord passes through the centre of a circle; equivalent statements stemming from the uniqueness of the perpendicular bisector are:

- A perpendicular line from the centre of a circle bisects the chord.

- The line segment through the centre bisecting a chord is perpendicular to the chord.

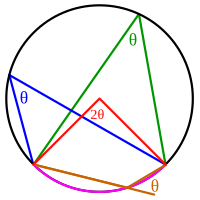

- If a central angle and an inscribed angle of a circle are subtended by the same chord and on the same side of the chord, then the central angle is twice the inscribed angle.

- If two angles are inscribed on the same chord and on the same side of the chord, then they are equal.

- If two angles are inscribed on the same chord and on opposite sides of the chord, then they are supplementary.

- For a cyclic quadrilateral, the exterior angle is equal to the interior opposite angle.

- An inscribed angle subtended by a diameter is a right angle (see Thales' theorem).

- The diameter is the longest chord of the circle.

- Among all the circles with a chord AB in common, the circle with minimal radius is the one with diameter AB.

- If the intersection of any two chords divides one chord into lengths a and b and divides the other chord into lengths c and d, then ab = cd.

- If the intersection of any two perpendicular chords divides one chord into lengths a and b and divides the other chord into lengths c and d, then a + b + c + d equals the square of the diameter.

- The sum of the squared lengths of any two chords intersecting at right angles at a given point is the same as that of any other two perpendicular chords intersecting at the same point and is given by 8r − 4p, where r is the circle radius, and p is the distance from the centre point to the point of intersection.

- The distance from a point on the circle to a given chord times the diameter of the circle equals the product of the distances from the point to the ends of the chord.

Tangent

- A line drawn perpendicular to a radius through the end point of the radius lying on the circle is a tangent to the circle.

- A line drawn perpendicular to a tangent through the point of contact with a circle passes through the centre of the circle.

- Two tangents can always be drawn to a circle from any point outside the circle, and these tangents are equal in length.

- If a tangent at A and a tangent at B intersect at the exterior point P, then denoting the centre as O, the angles ∠BOA and ∠BPA are supplementary.

- If AD is tangent to the circle at A and if AQ is a chord of the circle, then ∠DAQ = 1/2arc(AQ).

Theorems

- The chord theorem states that if two chords, CD and EB, intersect at A, then AC × AD = AB × AE.

- If two secants, AE and AD, also cut the circle at B and C respectively, then AC × AD = AB × AE (corollary of the chord theorem).

- A tangent can be considered a limiting case of a secant whose ends are coincident. If a tangent from an external point A meets the circle at F and a secant from the external point A meets the circle at C and D respectively, then AF = AC × AD (tangent–secant theorem).

- The angle between a chord and the tangent at one of its endpoints is equal to one half the angle subtended at the centre of the circle, on the opposite side of the chord (tangent chord angle).

- If the angle subtended by the chord at the centre is 90°, then ℓ = r √2, where ℓ is the length of the chord, and r is the radius of the circle.

- If two secants are inscribed in the circle as shown at right, then the measurement of angle A is equal to one half the difference of the measurements of the enclosed arcs ( and ). That is, , where O is the centre of the circle (secant–secant theorem).

Inscribed angles

See also: Inscribed angle theorem

An inscribed angle (examples are the blue and green angles in the figure) is exactly half the corresponding central angle (red). Hence, all inscribed angles that subtend the same arc (pink) are equal. Angles inscribed on the arc (brown) are supplementary. In particular, every inscribed angle that subtends a diameter is a right angle (since the central angle is 180°).

Sagitta

The sagitta (also known as the versine) is a line segment drawn perpendicular to a chord, between the midpoint of that chord and the arc of the circle.

Given the length y of a chord and the length x of the sagitta, the Pythagorean theorem can be used to calculate the radius of the unique circle that will fit around the two lines:

Another proof of this result, which relies only on two chord properties given above, is as follows. Given a chord of length y and with sagitta of length x, since the sagitta intersects the midpoint of the chord, we know that it is a part of a diameter of the circle. Since the diameter is twice the radius, the "missing" part of the diameter is (2r − x) in length. Using the fact that one part of one chord times the other part is equal to the same product taken along a chord intersecting the first chord, we find that (2r − x)x = (y / 2). Solving for r, we find the required result.

Compass and straightedge constructions

There are many compass-and-straightedge constructions resulting in circles.

The simplest and most basic is the construction given the centre of the circle and a point on the circle. Place the fixed leg of the compass on the centre point, the movable leg on the point on the circle and rotate the compass.

Construction with given diameter

- Construct the midpoint M of the diameter.

- Construct the circle with centre M passing through one of the endpoints of the diameter (it will also pass through the other endpoint).

Construction through three noncollinear points

- Name the points P, Q and R,

- Construct the perpendicular bisector of the segment PQ.

- Construct the perpendicular bisector of the segment PR.

- Label the point of intersection of these two perpendicular bisectors M. (They meet because the points are not collinear).

- Construct the circle with centre M passing through one of the points P, Q or R (it will also pass through the other two points).

Circle of Apollonius

See also: Circles of Apollonius

Apollonius of Perga showed that a circle may also be defined as the set of points in a plane having a constant ratio (other than 1) of distances to two fixed foci, A and B. (The set of points where the distances are equal is the perpendicular bisector of segment AB, a line.) That circle is sometimes said to be drawn about two points.

The proof is in two parts. First, one must prove that, given two foci A and B and a ratio of distances, any point P satisfying the ratio of distances must fall on a particular circle. Let C be another point, also satisfying the ratio and lying on segment AB. By the angle bisector theorem the line segment PC will bisect the interior angle APB, since the segments are similar:

Analogously, a line segment PD through some point D on AB extended bisects the corresponding exterior angle BPQ where Q is on AP extended. Since the interior and exterior angles sum to 180 degrees, the angle CPD is exactly 90 degrees; that is, a right angle. The set of points P such that angle CPD is a right angle forms a circle, of which CD is a diameter.

Second, see for a proof that every point on the indicated circle satisfies the given ratio.

Cross-ratios

A closely related property of circles involves the geometry of the cross-ratio of points in the complex plane. If A, B, and C are as above, then the circle of Apollonius for these three points is the collection of points P for which the absolute value of the cross-ratio is equal to one:

Stated another way, P is a point on the circle of Apollonius if and only if the cross-ratio is on the unit circle in the complex plane.

Generalised circles

See also: Generalised circleIf C is the midpoint of the segment AB, then the collection of points P satisfying the Apollonius condition is not a circle, but rather a line.

Thus, if A, B, and C are given distinct points in the plane, then the locus of points P satisfying the above equation is called a "generalised circle." It may either be a true circle or a line. In this sense a line is a generalised circle of infinite radius.

Inscription in or circumscription about other figures

In every triangle a unique circle, called the incircle, can be inscribed such that it is tangent to each of the three sides of the triangle.

About every triangle a unique circle, called the circumcircle, can be circumscribed such that it goes through each of the triangle's three vertices.

A tangential polygon, such as a tangential quadrilateral, is any convex polygon within which a circle can be inscribed that is tangent to each side of the polygon. Every regular polygon and every triangle is a tangential polygon.

A cyclic polygon is any convex polygon about which a circle can be circumscribed, passing through each vertex. A well-studied example is the cyclic quadrilateral. Every regular polygon and every triangle is a cyclic polygon. A polygon that is both cyclic and tangential is called a bicentric polygon.

A hypocycloid is a curve that is inscribed in a given circle by tracing a fixed point on a smaller circle that rolls within and tangent to the given circle.

Limiting case of other figures

The circle can be viewed as a limiting case of various other figures:

- The series of regular polygons with n sides has the circle as its limit as n approaches infinity. This fact was applied by Archimedes to approximate π.

- A Cartesian oval is a set of points such that a weighted sum of the distances from any of its points to two fixed points (foci) is a constant. An ellipse is the case in which the weights are equal. A circle is an ellipse with an eccentricity of zero, meaning that the two foci coincide with each other as the centre of the circle. A circle is also a different special case of a Cartesian oval in which one of the weights is zero.

- A superellipse has an equation of the form for positive a, b, and n. A supercircle has b = a. A circle is the special case of a supercircle in which n = 2.

- A Cassini oval is a set of points such that the product of the distances from any of its points to two fixed points is a constant. When the two fixed points coincide, a circle results.

- A curve of constant width is a figure whose width, defined as the perpendicular distance between two distinct parallel lines each intersecting its boundary in a single point, is the same regardless of the direction of those two parallel lines. The circle is the simplest example of this type of figure.

Locus of constant sum

Consider a finite set of points in the plane. The locus of points such that the sum of the squares of the distances to the given points is constant is a circle, whose centre is at the centroid of the given points. A generalisation for higher powers of distances is obtained if under points the vertices of the regular polygon are taken. The locus of points such that the sum of the -th power of distances to the vertices of a given regular polygon with circumradius is constant is a circle, if whose centre is the centroid of the .

In the case of the equilateral triangle, the loci of the constant sums of the second and fourth powers are circles, whereas for the square, the loci are circles for the constant sums of the second, fourth, and sixth powers. For the regular pentagon the constant sum of the eighth powers of the distances will be added and so forth.

Squaring the circle

Main article: Squaring the circleSquaring the circle is the problem, proposed by ancient geometers, of constructing a square with the same area as a given circle by using only a finite number of steps with compass and straightedge.

In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible, as a consequence of the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem, which proves that pi (π) is a transcendental number, rather than an algebraic irrational number; that is, it is not the root of any polynomial with rational coefficients. Despite the impossibility, this topic continues to be of interest for pseudomath enthusiasts.

Generalisations

In other p-norms

Defining a circle as the set of points with a fixed distance from a point, different shapes can be considered circles under different definitions of distance. In p-norm, distance is determined by In Euclidean geometry, p = 2, giving the familiar

In taxicab geometry, p = 1. Taxicab circles are squares with sides oriented at a 45° angle to the coordinate axes. While each side would have length using a Euclidean metric, where r is the circle's radius, its length in taxicab geometry is 2r. Thus, a circle's circumference is 8r. Thus, the value of a geometric analog to is 4 in this geometry. The formula for the unit circle in taxicab geometry is in Cartesian coordinates and in polar coordinates.

A circle of radius 1 (using this distance) is the von Neumann neighborhood of its centre.

A circle of radius r for the Chebyshev distance (L∞ metric) on a plane is also a square with side length 2r parallel to the coordinate axes, so planar Chebyshev distance can be viewed as equivalent by rotation and scaling to planar taxicab distance. However, this equivalence between L1 and L∞ metrics does not generalise to higher dimensions.

Topological definition

The circle is the one-dimensional hypersphere (the 1-sphere).

In topology, a circle is not limited to the geometric concept, but to all of its homeomorphisms. Two topological circles are equivalent if one can be transformed into the other via a deformation of R upon itself (known as an ambient isotopy).

Specially named circles

|

Of a triangle

|

Of certain quadrilaterals

Of a conic sectionOf a torus

|

See also

- Affine sphere

- Apeirogon

- Circle fitting

- Distance

- Gauss circle problem

- Inversion in a circle

- Line–circle intersection

- List of circle topics

- Sphere

- Three points determine a circle

- Translation of axes

Notes

- Also known as 𝜏 (tau).

References

- krikos Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Simek, Jan F.; Cressler, Alan; Herrmann, Nicholas P.; Sherwood, Sarah C. (1 June 2013). "Sacred landscapes of the south-eastern USA: prehistoric rock and cave art in Tennessee". Antiquity. 87 (336): 430–446. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00049048. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 130296519.

- Chronology for 30000 BC to 500 BC Archived 2008-03-22 at the Wayback Machine. History.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2012-05-03.

- OL 7227282M

- Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe (1959)

- Proclus, The Six Books of Proclus, the Platonic Successor, on the Theology of Plato Archived 2017-01-23 at the Wayback Machine Tr. Thomas Taylor (1816) Vol. 2, Ch. 2, "Of Plato"

- Squaring the circle Archived 2008-06-24 at the Wayback Machine. History.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2012-05-03.

- "Circles in a Circle". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- Lesso, Rosie (15 June 2022). "Why Did Wassily Kandinsky Paint Circles?". TheCollector. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- Abdullahi, Yahya (29 October 2019). "The Circle from East to West". In Charnier, Jean-François (ed.). The Louvre Abu Dhabi: A World Vision of Art. Rizzoli International Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 9782370741004.

- Katz, Victor J. (1998). A History of Mathematics / An Introduction (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley Longman. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-321-01618-8.

- Richeson, David (2015). "Circular reasoning: who first proved that C divided by d is a constant?". The College Mathematics Journal. 46 (3): 162–171. arXiv:1303.0904. doi:10.4169/college.math.j.46.3.162. MR 3413900.

- Posamentier and Salkind, Challenging Problems in Geometry, Dover, 2nd edition, 1996: pp. 104–105, #4–23.

- College Mathematics Journal 29(4), September 1998, p. 331, problem 635.

- Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007.

- Harkness, James (1898). "Introduction to the theory of analytic functions". Nature. 59 (1530): 30. Bibcode:1899Natur..59..386B. doi:10.1038/059386a0. S2CID 4030420. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008.

- Ogilvy, C. Stanley, Excursions in Geometry, Dover, 1969, 14–17.

- Altshiller-Court, Nathan, College Geometry, Dover, 2007 (orig. 1952).

- Incircle – from Wolfram MathWorld Archived 2012-01-21 at the Wayback Machine. Mathworld.wolfram.com (2012-04-26). Retrieved on 2012-05-03.

- Circumcircle – from Wolfram MathWorld Archived 2012-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. Mathworld.wolfram.com (2012-04-26). Retrieved on 2012-05-03.

- Tangential Polygon – from Wolfram MathWorld Archived 2013-09-03 at the Wayback Machine. Mathworld.wolfram.com (2012-04-26). Retrieved on 2012-05-03.

- Apostol, Tom; Mnatsakanian, Mamikon (2003). "Sums of squares of distances in m-space". American Mathematical Monthly. 110 (6): 516–526. doi:10.1080/00029890.2003.11919989. S2CID 12641658.

- Meskhishvili, Mamuka (2020). "Cyclic Averages of Regular Polygons and Platonic Solids". Communications in Mathematics and Applications. 11: 335–355. arXiv:2010.12340. doi:10.26713/cma.v11i3.1420 (inactive 1 November 2024). Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Gamelin, Theodore (1999). Introduction to topology. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486406806.

Further reading

- Pedoe, Dan (1988). Geometry: a comprehensive course. Dover. ISBN 9780486658124.

External links

- "Circle". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press. 2001 .

- Circle at PlanetMath.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Circle". MathWorld.

- "Interactive Java applets".

for the properties of and elementary constructions involving circles

- "Interactive Standard Form Equation of Circle".

Click and drag points to see standard form equation in action

- "Munching on Circles". Cut-the-Knot.

and required to be a positive number. A circle with

and required to be a positive number. A circle with  is a

is a

that is, approximately 79% of the

that is, approximately 79% of the

in the

in the  –

– plane can be broken into two semicircles each of which is the

plane can be broken into two semicircles each of which is the  and

and  , respectively:

, respectively:

for values of

for values of  to

to  .

.

where t is a

where t is a

not on a line is obtained by a conversion of the

not on a line is obtained by a conversion of the

are the polar coordinates of a generic point on the circle, and

are the polar coordinates of a generic point on the circle, and  are the polar coordinates of the centre of the circle (i.e., r0 is the distance from the origin to the centre of the circle, and φ is the anticlockwise angle from the positive x axis to the line connecting the origin to the centre of the circle). For a circle centred on the origin, i.e. r0 = 0, this reduces to r = a. When r0 = a, or when the origin lies on the circle, the equation becomes

are the polar coordinates of the centre of the circle (i.e., r0 is the distance from the origin to the centre of the circle, and φ is the anticlockwise angle from the positive x axis to the line connecting the origin to the centre of the circle). For a circle centred on the origin, i.e. r0 = 0, this reduces to r = a. When r0 = a, or when the origin lies on the circle, the equation becomes

Without the ± sign, the equation would in some cases describe only half a circle.

Without the ± sign, the equation would in some cases describe only half a circle.

, since

, since  . Not all generalised circles are actually circles: a generalised circle is either a (true) circle or a

. Not all generalised circles are actually circles: a generalised circle is either a (true) circle or a  or

or

and its slope is

and its slope is

and

and  ). That is,

). That is,  , where O is the centre of the circle (secant–secant theorem).

, where O is the centre of the circle (secant–secant theorem).

is not a circle, but rather a line.

is not a circle, but rather a line.

for positive a, b, and n. A supercircle has b = a. A circle is the special case of a supercircle in which n = 2.

for positive a, b, and n. A supercircle has b = a. A circle is the special case of a supercircle in which n = 2. points in the plane. The locus of points such that the sum of the squares of the distances to the given points is constant is a circle, whose centre is at the centroid of the given points.

A generalisation for higher powers of distances is obtained if under

points in the plane. The locus of points such that the sum of the squares of the distances to the given points is constant is a circle, whose centre is at the centroid of the given points.

A generalisation for higher powers of distances is obtained if under  are taken. The locus of points such that the sum of the

are taken. The locus of points such that the sum of the  -th power of distances

-th power of distances  to the vertices of a given regular polygon with circumradius

to the vertices of a given regular polygon with circumradius  is constant is a circle, if

is constant is a circle, if

whose centre is the centroid of the

whose centre is the centroid of the  In Euclidean geometry, p = 2, giving the familiar

In Euclidean geometry, p = 2, giving the familiar

using a

using a  is 4 in this geometry. The formula for the unit circle in taxicab geometry is

is 4 in this geometry. The formula for the unit circle in taxicab geometry is  in Cartesian coordinates and

in Cartesian coordinates and

in polar coordinates.

in polar coordinates.