| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

| Campaigns against corporal punishment |

School corporal punishment is the deliberate infliction of physical pain as a response to undesired behavior by students. The term corporal punishment derives from the Latin word for the "body", corpus. In schools it may involve striking the student on the buttocks or on the palms of their hands with an implement such as a rattan cane, wooden paddle, slipper, leather strap, belt, or wooden yardstick. Less commonly, it could also include spanking or smacking the student with an open hand, especially at the kindergarten, primary school, or other more junior levels.

Much of the traditional culture that surrounds corporal punishment in school, at any rate in the English-speaking world, derives largely from British practice in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly as regards the caning of teenage boys. There is a vast amount of literature on this, in both popular and serious culture.

In the English-speaking world, the use of corporal punishment in schools has historically been justified by the common-law doctrine in loco parentis, whereby teachers are considered authority figures granted the same rights as parents to discipline and punish children in their care if they do not adhere to the set rules. A similar justification exists in Chinese-speaking countries. It lets school officials stand in for parents as comparable authority figures. The doctrine has its origins in an English common-law precedent of 1770.

According to General Social Survey, 84 percent of American adults in 1986 believed that "children sometimes need a good spanking". There is hardly any evidence that corporal punishment improved a child's behavior as time goes by. On the other hand, substantial evidence is found that it puts children "at risk for negative outcomes," for it may result in increased aggression, antisocial behavior, mental health problems, and physical injury.

Poland was the first nation to outlaw corporal punishment in schools in 1783. School corporal punishment is no longer legal in European countries except for Belarus, Vatican City (however, there are no primary or secondary schools in Vatican City) and unrecognized Transnistria. By 2016, an estimated 128 countries had prohibited corporal punishment in schools, including nearly all of Europe and most of South America and East Asia. Approximately 69 countries still allow corporal punishment in schools, including parts of the United States and many countries in Africa and Asia.

Definitions

Corporal punishment in the context of schools in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has been variously defined as: causing deliberate pain to a child in response to the child's undesired behavior and/or language, "purposeful infliction of bodily pain or discomfort by an official in the educational system upon a student as a penalty for unacceptable behavior", and "intentional application of physical pain as a means of changing behavior" (not the occasional use of physical restraint to protect student or others from immediate harm).

Prevalence

Corporal punishment used to be prevalent in schools in many parts of the world, but in recent decades it has been outlawed in 128 countries including all of Europe and most of South America, as well as in Canada, Japan, South Africa, New Zealand and several other countries. It remains commonplace in a number of countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East (see list of countries, below).

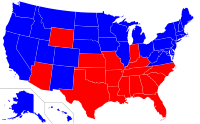

While most U.S. states have outlawed corporal punishment in state schools, it continues to be allowed mostly in the Southern states. According to the United States Department of Education, more than 216,000 students were subjected to corporal punishment during the 2008–09 school year.

Britain itself outlawed the practice in 1987 for state schools and more recently, in 1998, for all private schools.

In most of continental Europe, school corporal punishment has been banned for several decades or longer, depending on the country (see the list of countries below).

From the 1917 Russian revolution onwards, corporal punishment was outlawed in the Soviet Union, because it was deemed contrary to communist ideology. Communists in other countries such as Britain took the lead in campaigning against school corporal punishment, which they viewed as a symptom of the decadence of capitalist education systems. In the 1960s, Soviet visitors to western schools expressed shock at the canings witnessed there. Other communist regimes followed suit: for instance, corporal punishment was "unknown" by students in North Korea in 2007. In mainland China, corporal punishment in schools was outlawed in 1986, although the practice remains common, especially in rural areas.

Many schools in Singapore and Malaysia use caning for boys as a routine official punishment for misconduct, as also some African countries. In some Middle Eastern countries whipping is used. (See list of countries, below.)

In many countries, like Thailand, where the corporal punishment of students is technically illegal, it remains widespread and accepted in practice (for both boys and girls).

Effects on students

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), there are three broad rationales for the use of corporal punishment in schools: beliefs, based in traditional religion, that adults have a right, if not a duty, to physically punish misbehaving children; a disciplinary philosophy that corporal punishment builds character, being necessary for the development of a child's conscience and their respect for adult authority figures; and beliefs concerning the needs and rights of teachers, specifically that corporal punishment is essential for maintaining order and control in the classroom.

School teachers and policymakers often rely on personal anecdotes to argue that school corporal punishment improves students' behavior and achievements. However, there is a lack of empirical evidence showing that corporal punishment leads to better control in the classrooms. In particular, evidence does not suggest that it enhances moral character development, increases students' respect for teachers or other authority figures, or offers greater security for teachers.

A number of medical, pediatric or psychological societies have issued statements opposing all forms of corporal punishment in schools, citing such outcomes as poorer academic achievements, increases in antisocial behaviours, injuries to students, and an unwelcoming learning environment. They include the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the AAP, the Society for Adolescent Medicine, the American Psychological Association, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the Canadian Paediatric Society and the Australian Psychological Society, as well as the United States' National Association of Secondary School Principals.

According to the AAP, research shows that corporal punishment is less effective than other methods of behaviour management in schools, and "praise, discussions regarding values, and positive role models do more to develop character, respect, and values than does corporal punishment". They say that evidence links corporal punishment of students to a number of adverse outcomes, including: "increased aggressive and destructive behaviour, increased disruptive classroom behaviour, vandalism, poor school achievement, poor attention span, increased drop-out rate, school avoidance and school phobia, low self-esteem, anxiety, somatic complaints, depression, suicide and retaliation against teachers". The AAP recommends a number of alternatives to corporal punishment including various nonviolent behaviour-management strategies, modifications to the school environment, and increased support for teachers.

Injuries to students

An estimated 1 to 2 percent of physically punished students in the United States are seriously injured, to the point of needing medical attention. According to the AAP and the Society for Adolescent Medicine, these injuries have included bruises, abrasions, broken bones, whiplash injury, muscle damage, brain injury, and even death. Other reported injuries to students include "sciatic nerve damage", "extensive hematomas", and "life-threatening fat hemorrhage".

Promotion of violence

The AAP cautions that there is a risk of corporal punishment in schools fostering the impression among students that violence is an appropriate means for managing others' behaviour. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, "Corporal punishment signals to the child that a way to settle interpersonal conflicts is to use physical force and inflict pain". And according to the Society for Adolescent Medicine, "The use of corporal punishment in schools promotes a very precarious message: that violence is an acceptable phenomenon in our society. It sanctions the notion that it is meritorious to be violent toward our children, thereby devaluing them in society's eyes. It encourages children to resort to violence because they see their authority figures or substitute parents doing it ... Violence is not acceptable and we must not support it by sanctioning its use by such authority figures as school officials".

Alternatives

The Society for Adolescent Medicine recommends developing "a milieu of effective communication, in which the teacher displays an attitude of respect for the students", as well as instruction that is stimulating and appropriate to student's abilities, various nonviolent behaviour modification techniques, and involving students and parents in making decisions about school matters such as rules and educational goals. They suggest that student self-governance can be an effective alternative for managing disruptive classroom behaviour, while stressing the importance of adequate training and support for teachers.

The AAP remarks that there has been "no reported increase in disciplinary problems in schools following the elimination of corporal punishment" according to evidence.

Student rights

A number of international human-rights organizations including the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights have stated that physical punishment of any kind is a violation of children's human rights.

According to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, "Children do not lose their human rights by virtue of passing through the school gates ... the use of corporal punishment does not respect the inherent dignity of the child nor the strict limits on school discipline". The Committee interprets Article 19 of the Convention on the rights of the child, which obliges member states to "take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse … while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child", to imply a prohibition on all forms of corporal punishment.

Other international human-rights bodies supporting prohibition of corporal punishment of children in all settings, including schools, include the European Committee of Social Rights and the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. In addition, the obligation of member states to prohibit corporal punishment in schools and elsewhere was affirmed in the 2009 Cairo Declaration on the Convention on the Rights of the Child and Islamic Jurisprudence.

By country

School corporal punishment in the United States

School corporal punishment in the United StatesCorporal punishment of minors in the United States

Legality of corporal punishment of minors in Europe

Legality of corporal punishment of minors in Europe

Corporal punishment illegal in both schools and the home Corporal punishment illegal in schools only Corporal punishment legal in schools and in the home

According to the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, all forms of corporal punishment in schools are outlawed in 128 countries as of 2023. (65 of these countries also prohibited corporal punishment of children in the home as of October 2023).

Abkhazia and South Ossetia

In Abkazia and South Ossetia, two partially recognized states that are considered by most countries the occupied territories of Georgia, corporal punishment in schools is legal and common in practice. Both countries have nearly identical school corporal punishment laws. It can be inflicted on male students only. Both caning and belting methods are allowed, and the practice has sometimes been described as "cruel", with some South Ossetian boys caned or belted for more than 15 times as a result of minor school discipline violations, such like being late to classes or not wearing full uniform.

Argentina

Banned in 1813, corporal punishment was re-legalised in 1815 and physical punishments lasted legally until 1884, when their usage was banned (with the exception of court ordered punishments). Punishments include hitting with rebenques and slapping in the face. Corporal punishment of children has been prohibited unilaterally within the country since 2016.

Australia

In Australia, caning used to be common in schools for both boys and girls but has been effectively banned since the late 80's, with the practice gradually abandoned up to a decade earlier as cultural and social norms shifted. Laws on corporal punishment in schools are determined at individual state or territory level.

Legislation also varies among states and territories with regard to corporal punishment meted out to children in other care settings. According to the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, "Prohibition is still to be achieved in the home in all states/territories and in alternative care settings, day care, schools and penal institutions in some states/territories".

| State | Government schools | Non-government schools |

|---|---|---|

| Victoria | Banned in 1983. | Banned in 2006. |

| Queensland | Banned in 1994. | Not banned. |

| New South Wales | First banned in 1987. Ban repealed in 1989 but was in disuse. Banned again in 1995. |

Banned in 1997. |

| Tasmania | Banned in 1999. | Banned in 1999. |

| Australian Capital Territory | Banned in 1988. | Banned in 1997. |

| Northern Territory | Banned in 2015. | Banned in 2015. |

| South Australia | Banned in 1991. | Banned in 2019. |

| Western Australia | Banned in 1999. (Effectively abolished by Education Department policy in 1987.) |

Banned in 2015. |

Austria

Corporal punishment in schools was banned in Austria in 1974.

Bolivia

Corporal punishment in all settings, including schools, was prohibited in Bolivia in 2014. According to the Children and Adolescents Code, "The child and adolescent has the right to good treatment, comprising a non-violent upbringing and education... Any physical, violent and humiliating punishment is prohibited".

Brazil

Corporal punishment in all settings, including schools, was prohibited in Brazil in 2014. According to an amendment to the Code on Children and Adolescents 1990, "Children and Adolescents are entitled to be educated and cared for without the use of physical punishment or cruel or degrading treatment as forms of correction, discipline, education or any other pretext".

Canada

In many parts of Canada, 'the strap' had not been used in public schools since the 1970s or even earlier: thus, it has been claimed that it had not been used in Quebec since the 1960s, and in Toronto it was banned in 1971. However, some schools in Alberta had been using the strap up until the ban in 2004.

In public schools, the usual implement was a rubber/canvas/leather strap applied to the hands or sometimes, legs, while private schools sometimes used a paddle or cane administered to the student's posterior. This was used on boys and girls alike.

In 2004 (Canadian Foundation for Children, Youth and the Law v. Canada), the Supreme Court of Canada outlawed corporal punishment in all schools, public or private. The practice itself had largely been abandoned in the 1970s when parents placed greater scrutiny on the treatment of children at school. The subject received extensive media coverage, and corporal punishment became obsolete as the practice was widely seen as degrading and inhumane. Even though the tradition had been forgone for nearly 30 years, legislation banning the practice entirely by law was not implemented until 2004.

Some Canadian provinces banned corporal punishment in public schools prior to the national ban in 2004. They are, in chronological order by year of provincial ban:

- British Columbia - 1973

- Nova Scotia - 1989

- New Brunswick - 1990

- Yukon - 1990

- Prince Edward Island - 1993

- Northwest Territories - 1995

- Nunavut - 1995* (banned while Nunavut was still part of Northwest Territories. Remained banned in Nunavut when it became a separate Territory in 1999.)

- Newfoundland and Labrador - 1997

- Quebec - 1998

China

Corporal punishment in China was officially banned after the Communist Revolution in 1949. The Compulsory Education Law of 1986 states: "It shall be forbidden to inflict physical punishment on students". In practice, beatings by schoolteachers are quite common, especially in rural areas.

Colombia

Colombian private and public schools were banned from using "penalties involving physical or psychological abuse" through the Children and Adolescents Code 2006, though it is not clear whether this also applies to indigenous communities.

Costa Rica

All corporal punishment, both in school and in the home, has been banned since 2008.

Czech Republic

Corporal punishment is outlawed under Article 31 of the Education Act.

Denmark

Corporal punishment was prohibited in the public schools in Copenhagen Municipality in 1951 and by law in all schools of Denmark on 14 June 1967.

Egypt

A 1998 study found that random physical punishment (not proper formal corporal punishment) was being used extensively by teachers in Egypt to punish behavior they regarded as unacceptable. Around 80% of the boys and 60% of the girls were punished by teachers using their hands, sticks, straps, shoes, punches, and kicks as most common methods of administration. The most common reported injuries were bumps and contusions.

Finland

Corporal punishment in public schools was banned in 1914, but remained de facto commonplace until 1984, when a law banning all corporal punishment of minors, whether in schools or in the home, was introduced.

France

Caning was not unknown for French students in the 19th century, but they were described as "extremely sensitive" to corporal punishment and tended to make a "fuss" about its imposition. The systematic use of corporal punishment has been absent from French schools since the 19th century. Corporal punishment is considered unlawful in schools under article 371-1 of the Civil Code. There was no explicit legal ban on it, but in 2008 a teacher was fined €500 for what some people describe as slapping a student. In 2019, the Law on the Prohibition of Ordinary Educational Violence eventually banned all corporal punishment in France, including schools and the home.

Germany

School corporal punishment, historically widespread, was outlawed in different states via their administrative law at different times. It was not completely abolished everywhere until 1983. Since 1993, use of corporal punishment by a teacher has been a criminal offence. In that year a sentence by the Federal Court of Justice of Germany (Bundesgerichtshof, case number NStZ 1993.591) was published which overruled the previous powers enshrined in unofficial customary law (Gewohnheitsrecht) and upheld by some regional appeal courts (Oberlandesgericht, Superior State Court) even in the 1970s. They assumed a right of chastisement was a defense of justification against the accusation of "causing bodily harm" per Paragraph (=Section) 223 Strafgesetzbuch (Federal Penal Code).

Greece

Corporal punishment in Greek primary schools was banned in 1998, and in secondary schools in 2005.

India

See also: Education in IndiaIn India, corporal punishment is banned in schools, daycare and alternative child care institutions. However, there are no prohibitions of it at home. The National Policy for Children 2013 states that in education, the state shall "ensure no child is subjected to any physical punishment or mental harassment" and "promote positive engagement to impart discipline so as to provide children with a good learning experience". Corporal punishment is also prohibited by the Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009 (RTE Act). Article 17 states: "(1) No child shall be subjected to physical punishment or mental harassment. (2) Whoever contravenes the provisions of sub-section (1) shall be liable to disciplinary action under the service rules applicable to such person." The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Rules 2010 provide for implementation of the Act, including awareness raising about the rights in the Act, procedures for monitoring implementation, and complaints mechanisms when the rights are violated. In 2014, the Ministry of Human Resources Development issued guidance ("Advisory for Eliminating Corporal Punishment in Schools under Section 35(1) of the RTE Act 2009") which sets out the national law relevant to corporal punishment in schools, the international human rights standards, steps that may be taken to promote positive child development and not resorting to corporal punishment, and the role of national bodies in implementing the RTE Act, stating: "This advisory should be used by the State Governments/UT Administrations to ensure that appropriate State/school level guidelines on prevention of corporate punishment and appropriate redressal of any complaints, are framed, disseminated, acted upon and monitored."

However, corporal punishment is still widely prevalent in schools in Indian rural communities.

Iran

On 10 August 2000, Iran "Supreme Council of Education" (شورای عالی آموزش وپرورش) (under supervision of Ministry of Education (Iran)(وزارت آموزش و پرورش)) approved an executive regulations for Iranian schools that any verbal and physical punishment for students are forbidden under the article no. 77. Iran parliament Islamic Consultative Assembly (مجلس شورای اسلامی) approved "Child and Adolescent Protection Law" (قانون حمایت از کودکان و نوجوانان) on 16 December 2002 citing that any harassment for children and teenager (under 18 years old) that is causing any physical/mental/moral damages is forbidden under article no.2.

Ireland

In the law of the Republic of Ireland, corporal punishment was prohibited in 1982 by an administrative decision of John Boland, the Minister for Education, which applied to national schools (most primary schools) and to secondary schools receiving public funding (practically all of them). Teachers were not liable to criminal prosecution until 1997, when the rule of law allowing "physical chastisement" was explicitly abolished.

Israel

A 1994 Supreme Court ruling in The State of Israel v Alagani declared that "corporal punishment cannot constitute a legitimate tool in the hands of teachers or other educators", applicable to both state and private schools.

On 25 January 2000, the Supreme Court of Israel issued the landmark Plonit decision ruling that "corporal punishment of children by their parents is never educational", "always causes serious harm to the children" and "is indefensible". This decision repealed section 7 of article 27 of the Civil Wrongs Ordinance 1944, which provided a defence for the use of corporal punishment in childrearing, and stated that "the law imposes an obligation on state authorities to intervene in the family unit and to protect the child when necessary, including from his parents." Soon after, a new Pupils' Rights Law, 5760-2000 established (art. 10) that "it is the right of every pupil that discipline be maintained in the educational institution in conformity with human dignity and, in that regard, he has the right not to be subjected to corporal or degrading disciplinary measures."

Italy

Corporal punishment in Italian schools has a long history but was officially banned in 1928. Despite the official ban, instances of corporal punishment have occasionally been reported in Italian schools, albeit infrequently and usually in rural or underfunded areas. Such cases are typically met with strong public condemnation and legal repercussions for the perpetrators.

Japan

Although banned in 1947, corporal punishment was still commonly found in schools in the 2010s and particularly widespread in school sports clubs. In late 1987, about 60% of junior high school teachers felt it was necessary, with 7% believing it was necessary in all conditions, 59% believing it should be applied sometimes and 32% disapproving of it in all circumstances; while at elementary (primary) schools, 2% supported it unconditionally, 47% felt it was necessary and 49% disapproved. As recently as December 2012, a high school student died by suicide after being physically punished by his coach. An education ministry survey found that more than 10,000 students received illegal corporal punishment from more than 5,000 teachers across Japan in 2012 fiscal year alone. Corporal punishment has been banned in all settings in Japan since April 2020.

Luxembourg

Corporal punishment in schools was banned in 1845 and became a criminal offence in 1974 (Aggravated Assault on Minors under Authority).

Malaysia

Caning, usually applied to the palm or clothed bottom, is a common form of discipline in Malaysian schools. Although it is legally permitted for boys only, in practice the illegal caning of girls is not unknown. There have been reports of students being caned in front of the class/school for lateness, poor grades, being unable to answer questions correctly or forgetting to bring a textbook. In November 2007, in response to a perceived increase in indiscipline among female students, the National Seminar on Education Regulations (Student Discipline) passed a resolution recommending allowing the caning of girls at school.

Moldova

The Education Act of 2008 prohibits all corporal punishment in schools.

Myanmar

Caning is commonly used by teachers as a punishment in schools. The cane is applied on the students' buttocks, calves or palms of the hands in front of the class. Sit-ups with ears pulled and arms crossed, kneeling, and standing on the bench in the classroom are other forms of punishment used in schools. Common reasons for punishment include talking in class, not finishing homework, mistakes made with classwork, fighting, and truancy.

Nepal

All corporal punishment, both in school and in the home, has been banned since 2018.

Netherlands

Caning and other forms of corporal punishment in schools was abolished in 1920.

New Zealand

In New Zealand's schools, corporal punishment was used commonly on both girls and boys. This was abolished in practice in 1987. However, teachers in New Zealand schools had the right to use what the law called reasonable force to discipline students, mainly with a strap, cane or ruler, on the bottom or the hand.

This was criminalised on 23 July 1990, when Section 139A of the Education Act 1989 was inserted by the Education Amendment Act 1990. Section 139A prohibits anyone employed by a school or early childhood education (ECE) provider, or anyone supervising or controlling students on the school's behalf, from using force by way of correction or punishment towards any student at or in relation to the school or the student under their supervision or control. Teachers who administer corporal punishment can be found guilty of physical assault, resulting in termination and cancellation of teacher registration, and possibly criminal charges, with a maximum penalty of five years' imprisonment.

As enacted, the law had a loophole: parents, provided they were not school staff, could still discipline their children on school grounds. In early 2007, a southern Auckland Christian school was found to be using this loophole to discipline students by corporal punishment, by making the student's parents administer the punishment. This loophole was closed in May 2007 by the Crimes (Substituted Section 59) Amendment Act 2007, which enacted a blanket ban on parents administering corporal punishment to their children.

Norway

Corporal punishment in Norwegian schools was strongly restricted in 1889, and was banned outright in 1936. Nowadays, it is explicitly prohibited in sections 2.9 and 3.7 of the Education Act 1998,2 amended 2008: "Corporal punishment or other humiliating forms of treatment must not be used."

Pakistan

Article 89 of the Pakistan Penal Code does not prohibit actions, such as corporal punishment, subject to certain conditions (that no "grievous hurt" be caused, that the act should be done in "good faith", the recipient must be under 12 etc.). In 2013, the Pakistan National Assembly unanimously passed a bill that would override article 89 and ban all corporal punishment; however the bill did not pass in the senate. On the provincial level, corporal punishment was partially banned in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa by two laws in 2010 and 2012, and banned by Sindh in schools in 2013. Balochistan tried to ban the practice in 2011 and Punjab tried to ban it in 2012, but neither bill passed the respective provincial assembly.

School corporal punishment in Pakistan is not very common in modern educational institutions although it is still used in schools across the rural parts of the country as a means of enforcing student discipline. The method has been criticised by some children's rights activists who claim that many cases of corporal punishment in schools have resulted in physical and mental abuse of schoolchildren. According to one report, corporal punishment is a key reason for school dropouts and subsequently, street children, in Pakistan; as many as 35,000 high school pupils are said to drop out of the education system each year because they have been punished or abused in school.

Philippines

Corporal punishment has been prohibited in Filipino private and public schools since 1987. Although, many households in the country still use it to punish their children for misbehavior.

Poland

In 1783, Poland became the first country in the world to prohibit corporal punishment. Peter Newell assumes that perhaps the most influential writer on the subject was the English philosopher John Locke, whose Some Thoughts Concerning Education explicitly criticised the central role of corporal punishment in education. Locke's work was highly influential, and may have helped influence Polish legislators to ban corporal punishment from Poland's schools in 1783. Today, the ban of corporal punishment in all forms, whether in schools or in the home, is vested in the Constitution of Poland.

Russia

Corporal punishment was banned in Soviet (and hence Russian) schools immediately after the 1917 Russian Revolution. In addition, the Article 336 (since 2006) of the Labor Code of the Russian Federation states that "the use, including a single occurrence, of educational methods involving physical and/or psychological violence against a student or pupil" shall constitute grounds for dismissal of any teaching professional. Article 34 of the Law on Education 2012 states that students have the right to "(9) respect for human dignity, protection from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury personality, the protection of life and health"; article 43(3) states that "discipline in educational activities is provided on the basis of respect for human dignity of students and teachers" and "application of physical and mental violence to students is not allowed."

Serbia

Corporal punishment was first explicitly prohibited in schools in article 67 of the Public Schools Act 1929, passed in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, of which Serbia was then a part. In Serbia, corporal punishment in schools is now unlawful under the Secondary Schools Act 1992, the Elementary Schools Act 1992 and the Foundations of Education and Upbringing Act 2003/2009.

Sierra Leone

Corporal punishment of children remains legal in schools, homes, alternative care and day-care centres. Harsh caning of girls and boys remains very common in schools.

Singapore

Main article: Caning in Singapore § School caningCorporal punishment is legal in Singapore schools, for male students only (it is illegal to inflict it on female students) and fully encouraged by the government in order to maintain discipline. Only a light rattan cane may be used. This is administered in a formal ceremony by the school management after due deliberation, not by classroom teachers. Most secondary schools (whether independent, autonomous or government-controlled), and also some primary schools, use caning to deal with misconduct by boys. At the secondary level, the rattan strokes are nearly always delivered to the student's clothed buttocks. The Ministry of Education has stipulated a maximum of three strokes per occasion. In some cases, the punishment is carried out in front of the rest of the school instead of in private.

South Africa

The use of corporal punishment in schools was prohibited by the South African Schools Act, 1996. According to section 10 of the act:

(1) No person may administer corporal punishment at a school to a learner. (2) Any person who contravenes subsection (1) is guilty of an offence and liable on conviction to a sentence which could be imposed for assault.

In the case of Christian Education South Africa v Minister of Education the Constitutional Court rejected a claim that the constitutional right to religious freedom entitles private Christian schools to impose corporal punishment.

South Korea

Liberal regions in South Korea have completely banned all forms of caning beginning with Gyeonggi Province in 2010, followed by Seoul Metropolitan City, Gangwon Province, Gwangju Metropolitan City and North Jeolla Province in 2011. Other more conservative regions are governed by a national law enacted in 2011 which states that while caning is generally forbidden, it can be used indirectly to maintain school discipline.

However, caning was still known to be practised indiscriminately on both boys and girls as of 2015. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the caning of girls is not particularly unusual, and that they might be as likely to be caned as boys. Mass punishments in front of the class are common, and the large number of corporal punishment scenes in films suggest that caning is an accepted cultural norm in education.

All corporal punishment of children in South Korea has been prohibited since March 2021.

Spain

Spain banned school corporal punishment in 1985 under article 6 of the Right to Education (Organization) Act 8/1985. Those who broke this law risked losing job and career; as a result, this historically well-entrenched practice soon disappeared. Eventually, all forms of corporal punishment were banned in Spain in 2007.

Sweden

Corporal punishment at school has been prohibited in folkskolestadgan (the elementary school ordinance) since 1 January 1958. Its use by ordinary teachers in grammar schools had been outlawed in 1928. All forms of corporal punishment of children have been outlawed in Sweden since 1966, and have been strongly enforced since 1979.

Taiwan

Main article: Corporal punishment in TaiwanIn 2006, Taiwan made corporal punishment in the school system illegal.

Tanzania

In Tanzania, corporal punishment in schools is widely practised and has led to lasting damage, including the death of a punished pupil. The Education Act of 2002 authorizes the minister in charge of education to issue regulations concerning corporal punishment. The Education (Corporal Punishment) Regulation G.N. 294 of 2002 gives the authority to order corporal punishment to the headmaster of a school, who can delegate to any teacher on a case-by-case basis. The number of strikes must not be more than four for each occurrence. The school should have a register where date, reason, name of pupil and of administering teacher, together with the number of strikes, is to be recorded.

Thailand

Corporal punishment in schools is officially illegal under the Ministry of Education Regulation on Student Punishment 2005.

The proverb "If you love your cow, tie it up; if you love your child, beat him" is still considered "wisdom" and is held by many Thai parents and teachers. Corporal punishment (especially caning) on students of both genders remains common and accepted in practice. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the caning of girls is not particularly unusual, and that they are just as likely to be caned as boys.

Uganda

In Uganda, it is common practice for teachers to attempt to control large, overcrowded classes by corporal punishment. There is some movement of changing negative disciplining methods to positive ones (non-corporal), such as teaching students how to improve when they perform badly via verbal positive reinforcement.

Ukraine

Corporal punishment was banned in Soviet (and hence, Ukrainian) schools in 1917. In Ukraine, "physical or mental violence" against children is forbidden by the Constitution (Art.52.2) and the Law on Education (Art.51.1, since 1991) which states that students and other learners have the right "to the protection from any form of exploitation, physical and psychological violence, actions of pedagogical and other employees who violate the rights or humiliate their honour and dignity". Standard instructions for teachers provided by the Ministry of Science and Education state that a teacher who has used corporal punishment to a pupil (even once), shall be dismissed.

United Arab Emirates

A federal law was implemented in 1998 which banned school corporal punishment. The law applied to all schools, both public and private. Any teacher who engages in the practice would not only lose their job and teaching license, but will also face criminal prosecution for engaging in violence against minors and will also face child abuse charges.

United Kingdom

In state-run schools, and in private schools where at least part of the funding came from government, corporal punishment was outlawed by the British Parliament on 22 July 1986, following a 1982 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights that such punishment could no longer be administered without parental consent, and that a child's "right to education" could not be infringed by suspending children who, with parental approval, refused to submit to corporal punishment. In other private schools, it was banned in 1998 (England and Wales), 2000 (Scotland) and 2003 (Northern Ireland).

In 19th-century France, caning was dubbed "The English Vice", probably because of its widespread use in British schools. The regular depiction of caning in British novels about school life from the 19th century onwards, as well as movies such as If...., which includes a dramatic scene of boys caned by prefects, contributed to the French perception of caning as being central to the British educational system.

The implement used in many state and private schools in England and Wales was often a rattan cane, struck either across the student's hands, legs, or the clothed buttocks. It had been regularly used on boys and girls in certain schools for centuries prior to the ban.

Sometimes, a long ruler was used on the bare legs or hands instead of a cane. Striking the buttocks with a rubber-soled gym shoe, or plimsoll shoe (called slippering), was also widely used.

In Scotland, a leather strap, the tawse (sometimes called a belt), administered to the palms of the hands, was universal in state schools, but some private schools used the cane. This was wielded in primary as well as secondary schools for both trivial and serious offences, and girls were belted as well as boys. In a few English cities, a strap was used instead of the cane.

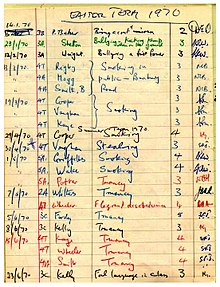

Schools had to keep a record of punishments inflicted, and there are occasional press reports of examples of these "punishment books" having survived.

By the 1970s, in the wake of the protest about school corporal punishment by thousands of school pupils who walked out of school to protest outside the Houses Of Parliament on 17 May 1972, corporal punishment was toned down in many state-run schools, and whilst many only used it as a last resort for misbehaving pupils, some state-run schools banned corporal punishment completely, most notably, London's Primary Schools, which had already began phasing out corporal punishment in the late 1960s.

Prior to the ban in private schools in England, the slippering of a student at an independent boarding school was challenged in 1993 before the European Court of Human Rights. The Court ruled 5–4 in that case that the punishment was not severe enough to infringe the student's "freedom from degrading punishment" under article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The dissenting judges argued that the ritualised nature of the punishment, given after several days and without parental consent, should qualify it as "degrading punishment".

R (Williamson) v Secretary of State for Education and Employment (2005) was an unsuccessful challenge to the prohibition of corporal punishment contained in the Education Act 1996, by several headmasters of private Christian schools who argued that it was a breach of their religious freedom.

In response to a 2008 poll of 6,162 UK teachers by the Times Educational Supplement, 22% of secondary school teachers and 16% of primary school teachers supported "the right to use corporal punishment in extreme cases". The National Union of Teachers said that it "could not support the views expressed by those in favour of hitting children".

United States

Main article: School corporal punishment in the United StatesThere is no federal law addressing corporal punishment in public or private schools. In 1977, the Supreme Court ruling in Ingraham v. Wright held that the Eighth Amendment clause prohibiting "cruel and unusual punishments" did not apply to school students, and that teachers could punish children without parental permission. In some cases, the parents are notified after, and at each punishment a witness is present. However, a lot of schools today send a waiver home stating to the parent if they agree to the corporal punishment as a disciplinary action for the school. If the parent declines, the school will not use it on the child.

As of 2024, 33 states and the District of Columbia have banned corporal punishment in public schools, though in some of these there is no explicit prohibition. Corporal punishment is also unlawful in private schools in Illinois, Iowa, New Jersey, Maryland and New York. In the remaining 17 U.S. states, corporal punishment is lawful in both public and private schools. It is still common in some schools in the South, and more than 167,000 students were paddled in the 2011–2012 school year in American public schools. Students can be physically punished from kindergarten to the end of high school, meaning that even legal adults who have reached the age of majority are sometimes spanked by school officials. Some American legal scholars have argued that school paddling is unconstitutional and can cause lasting physical, emotional, and cognitive harm.

Venezuela

Corporal punishment in all settings, including schools, was prohibited in Venezuela in 2007. According to the Law for the Protection of Children and Adolescents, "All children and young people have a right to be treated well. This right includes a non-violent education and upbringing... Consequently, all forms of physical and humiliating punishment are prohibited".

Vietnam

Corporal punishment is technically unlawful in schools under article 75 of the Education Law 2005, but there is no clear statement that corporal punishment is prohibited. Such punishment continues to be used, and there are frequent media reports of excessive corporal punishment in schools. The caning of girls is not particularly unusual, and girls are as likely to be caned at school as boys.

See also

- Corporal punishment in the home

- Campaigns against corporal punishment

- Child corporal punishment laws

- Blab school

- School bullying

- School discipline

- Boot camp and WWASP

Further reading

- Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (2017). "School corporal punishment in global perspective: prevalence, outcomes, and efforts at intervention". Psychology, Health & Medicine. 22: 224–239. – Includes a dataset on the legal status of school corporal punishment across the world.

References

- "Corporal Punishment in Schools". American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. September 2014.

- ^ Lind, Loren (23 July 1971). "Toronto abolishes the strap". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- https://brainly.in/question/18453211

- "United Kingdom: Corporal punishment in schools". World Corporal Punishment Research.

- Quigly, Isabel (1984). The Heirs of Tom Brown: The English School Story. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-281404-4

- Chandos, John (1984). Boys Together: English Public Schools 1800-1864. London: Hutchinson, esp. chapter 11. ISBN 0-09-139240-3

- Lu, Joy (27 May 2006). "Spare the rod and spoil the child?". China Daily. Beijing. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Poole, Steven R.; et al. (July 1991). "The role of the pediatrician in abolishing corporal punishment in schools". Pediatrics. 88 (1): 162–7. doi:10.1542/peds.88.1.162. PMID 2057255. S2CID 41234145.

- ^ Greydanus, D.E.; Pratt, H.D.; Spates, Richard C.; Blake-Dreher, A.E.; Greydanus-Gearhart, M.A.; Patel, D.R. (May 2003). "Corporal punishment in schools: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine" (PDF). J Adolesc Health. 32 (5): 385–93. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00042-9. PMID 12729988. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009.

- Gershoff, E.T.; Font, S.A. (2016). "Corporal punishment in U.S. public schools: Prevalence, disparities in use, and status in state and federal policy" (PDF). Social Policy Report. 30: 1–26. doi:10.1002/j.2379-3988.2016.tb00086.x. PMC 5766273. PMID 29333055.

- ^ Gershoff, Elizabeth (2017). "School corporal punishment in global perspective: prevalence, outcomes, and efforts at intervention". Psychology, Health & Medicine. 22 (sup1): sup1, 224–239. doi:10.1080/13548506.2016.1271955. PMC 5560991. PMID 28064515.

- ^ "Corporal Punishment in Schools". American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. September 2014.

- "Spanking Lives On In Rural Florida Schools".

- "Spare the rod". The Economist. London. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- "Education (No. 2) Act 1986", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1986 c. 61 Section 47 for England and Wales and section 48 for Scotland, brought into force in 1987.

- "The Education (Corporal Punishment) (Northern Ireland) Order 1987".

- Gould, Mark (9 January 2007). "Sparing the rod". The Guardian. London.

- "School Standards and Framework Act 1998", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1998 c. 31 Section 131, for England and Wales, brought into force in 1999.

- ^ Teitelbaum, Salomon M. (1945). "Parental Authority in the Soviet Union". The American Slavic and East European Review. 4 (3/4): 54–69. doi:10.2307/2491761. ISSN 1049-7544.

- Linehan, Thomas P. (2007). Communism in Britain, 1920-39: From the cradle to the grave, Manchester University Press. pp. 32 ff. ISBN 0-7190-7140-2

- "North Korean Defectors Face Huge Challenges". Radio Free Asia. 21 March 2007.

- ^ "Country report for China". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

- ^ Paul Wiseman, "Chinese schools try to unlearn brutality". USA Today. Washington D.C. 9 May 2000.

- Gershoff, Elizabeth T. (Spring 2010). "More Harm Than Good: A Summary of Scientific Research on the Intended and Unintended Effects of Corporal Punishment on Children". Law & Contemporary Problems. 73 (2): 31–56.

- "Corporal Punishment in Schools and its Effect on Academic Success: Testimony by Donald E. Greydanus MD" (PDF). Healthy Families and Communities Subcommittee, United States House of Representatives. 15 April 2010.

- "H-515.995 Corporal Punishment in Schools". American Medical Association.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on School Health (February 1984). "Corporal punishment in schools". Pediatrics. 73 (2): 258. doi:10.1542/peds.73.2.258. PMID 6599942. S2CID 245213800.

- Stein, M.T.; Perrin, E.L. (April 1998). "Guidance for effective discipline. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health". Pediatrics. 101 (4 Pt 1): 723–8. doi:10.1542/peds.101.4.723. PMID 9521967. S2CID 79545678.

- Corporal Punishment, Committee Ad Hoc; Greydanus, Donald E.; Pratt, Helen D.; Greydanus, Samuel E.; Hofmann, Adele D.; Tsegaye-Spates, C. Richard (May 1992). "Corporal punishment in schools. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine". J Adolesc Health. 13 (3): 240–6. doi:10.1016/1054-139X(92)90097-U. PMID 1498122.

- "Corporal Punishment". Council Policy Manual. American Psychological Association. 1975.

- "Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Position Statement on corporal punishment" (PDF). November 2009.

- Lynch, M. (September 2003). "Community pediatrics: role of physicians and organizations". Pediatrics. 112 (3 Part 2): 732–4. doi:10.1542/peds.112.S3.732. PMID 12949335. S2CID 35761650.

- "Memorandum on the Use of Corporal Punishment in Schools". Psychiatric Bulletin. 2 (4): 62–64. 1978. doi:10.1192/pb.2.4.62.

- Psychosocial Paediatrics Committee; Canadian Paediatric Society (2004). "Effective discipline for children". Paediatrics & Child Health. 9 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1093/pch/9.1.37. PMC 2719514. PMID 19654979.

- "Legislative assembly questions #0293 - Australian Psychological Society: Punishment and Behaviour Change". Parliament of New South Wales. 20 October 1996. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- "Corporal punishment". National Association of Secondary School Principals. February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010.

- "General comment No. 8 (2006): The right of the child to protection from corporal punishment and or cruel or degrading forms of punishment (articles 1, 28(2), and 37, inter alia)". United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 42nd Sess., U.N. Doc. CRC/C/GC/8. 2 March 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Europe-Wide Ban on Corporal Punishment of Children, Recommendation 1666". Parliamentary Assembly, Council of Europe (21st Sitting). 23 June 2004. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Report on Corporal Punishment and Human Rights of Children and Adolescents". Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Rapporteurship on the Rights of the Child, Organization of American States. 5 August 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (2001). General Comment No. 1, The Aims of Education. U.N. Doc. CRC/GC/2001/1.

- ^ Towards Non-violent Schools: Prohibiting All Corporal Punishment: Global Report 2015 (PDF), London: Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children; Save the Children, May 2015

- "Diálogo, premios y penitencias: cómo poner límites sin violencia" Archived 23 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. El Clarín (Buenos Aires). 17 December 2005. (in Spanish)

- "En Argentina, del golpe a la convivencia". El Clarín (Buenos Aires). 10 February 1999. (in Spanish)

- "Country report for Argentina". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

- Tarica, Elisabeth (8 May 2009). "Sparing the rod". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Murree, Erica (24 June 2015). "Laughter as alumni share stories about getting the cane". Queensland Times. Ipswich QLD. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Child Family Community Australia (March 2014), Corporal punishment: Key issues - Resource Sheet, Australian Government, archived from the original on 11 September 2015

- "Federal Government rules out return of corporal punishment, after curriculum adviser says it can be 'very effective'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014.

- "Corporal punishment: Key issues". Child Family Community Australia. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Australia". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. 24 October 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Ruff, Marcia (19 December 1985). "Senator keeps up fight against cane in schools". The Canberra Times. p. 2.

- Holzer, Prue. "Corporal punishment: Key issues" (PDF). corporalpunishment.pdf. National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- Criminal Code Act (Qld), s280.

- "Qld schools consign cane to history". The Canberra Times. 27 May 1992. p. 20.

Corporal punishment will be phased out by the end of the 1994 school year

- Pavey, Ainsley (11 November 2009). "Teachers given the cane go-ahead in some Queensland schools". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015.

- Education Act 1960 (NSW), s47(h), s3 and s 35 (2A)

- "Caning gets the cut from 1987". The Canberra Times. 13 December 1985. p. 18.

- "WA to decide on caning of girls". The Canberra Times. 24 May 1987. p. 3.

Following the decision, the NSW State Government banned the use of canes in all schools in that state.

- "NSW schools say no to use of the cane". The Canberra Times. 20 June 1989. p. 11.

The Fair Discipline Code... reversed the NSW Labor Government's two-year-old ban on the cane for the state's 2300 schools

- ^ "NSW vetoes school cane". The Canberra Times. 6 December 1995. p. 8.

NSW Education Minister John Aquilina said corporal punishment would be outlawed in public schools from today, and in non-government schools from 1997

- "Cane ban no bar to discipline: Carr". The Canberra Times. 17 December 1995. p. 2.

- Education Act 1994 (Tas), s82A.

- ^ Haley, Martine (8 April 2001). "Spank curb Bid for child punishment laws". Sunday Tasmanian. p. 1.

- Habel, Bernadette (2 June 2014). "Leaders against return to corporal punishment". The Examiner. Launceston, Tasmania. p. 6.

- Education Act 2004 (ACT), s7(4).

- Zakharov, Jeannie (20 November 1987). "ACT Schools Authority decides to abolish cane". The Canberra Times. p. 14.

- Hobson, Karen (13 July 1991). "Libs push for discipline codes, including corporal punishment, in ACT schools". The Canberra Times. p. 1.

- Criminal Code Act (NT), s11.

- ^ Corbett, Alan (27 June 2016). "The Last Hold-Out Caves: The Slow Death Of Corporal Punishment In Our Schools". New Matilda. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Education and Children's Services Act 2019 - SECT 32". Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII). Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- School Education Regulations, s40, cf Criminal Code Act, s257.

- "School Education Bill - Committee". Hansard. Parliament of Western Australia. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Last WA school using corporal punishment forced to end practice from next term". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015.

- Burrell, Andrew (8 January 2015). "Corporal punishment ban widened". The Australian. p. 3.

- Austria State Report Archived 20 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC.

- "Prohibition of all corporal punishment in Bolivia (2014)". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

- "Brazil Prohibits All Corporal Punishment". Save the Children. 2 July 2014.

- ^ Block, Irwin (23 February 2005). "Spanking still legal in Canada". The Gazette. Montreal.

- "Peace Wapiti scraps strap". Daily Herald-Tribune. Grande Prairie, Alberta. 19 November 2004.

- ^ "strap". www3.sympatico.ca. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Moyers school supplies catalogue", 1971.

- FitzGerald, James (1994).Old Boys: The Powerful Legacy of Upper Canada College. Toronto: Macfarlane Walter & Ross. ISBN 0-921912-74-9

- Byfield, Ted (21 October 1996). "Do our new-found ideas on children maybe explain the fact we can't control them?". Alberta Report. Edmonton.

- "Web links: Corporal punishment in schools". World Corporal Punishment Research. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Naylor, Cornelia (30 October 2015). "Oh my god, this is the strap!". Burnaby Now. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Supreme Court takes strap out of teachers' hands". Edmonton Journal. 1 February 2004.

- "Corporal Punishment ~ Canada's Human Rights History". 23 February 2015.

- "New measures taken in schools to improve teacher-student relations", People's Daily, Beijing, 31 July 2005.

- "Colombia country report - Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children". www.endcorporalpunishment.org. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Gillers, Gillian (27 June 2008). "Costa Rica lawmakers ban spanking". The Tico Times. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Czech Republic State Report Archived 8 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC, June 2011.

- Danish School History 1814-2014, Danmarkshistorien.dk, 2014.

- Danish School History, Den Store Danske Encyklopædi.

- Illegal corporal punishment, Folkeskolen, 3 October 2002.

- Youssef RM, Attia MS, Kamel MI; Attia; Kamel (October 1998). "Children experiencing violence. II: Prevalence and determinants of corporal punishment in schools". Child Abuse Negl. 22 (10): 975–85. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00084-2. PMID 9793720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kolsi, Eeva-Kaarina (11 June 2016). "Kansakoulun perustamisesta 150 vuotta – lukemisen pelättiin laiskistavan". Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Autio, Raisa (9 April 2014). "Lasten ruumiillinen kuritus kiellettiin 30 vuotta sitten – vielä joka neljäs tukistaa". YLE Uutiset (in Finnish). Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Hope, Ascott Robert (1882). A book of boyhoods. London: J. Hogg. p. 154. OCLC 559876116.

- "The punishments in French schools are impositions and confinements."-- Matthew Arnold (1861) cited in Robert McCole Wilson, A Study of Attitudes Towards Corporal Punishment as an Educational Procedure From the Earliest Times to the Present Archived 10 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Nijmegen University, 1999, 4.3.

- France State Report February 2008 Archived 20 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC.

- "Teacher Fined, Praised for Slap", Time (New York), 14 August 2008.

- Desnos, Marie (13 August 2008). "Une gifle à 500 euros". Le Journal du Dimanche (Paris).

- Rosenczveig, Jean-Pierre (1 February 2008)."Violences non retenues au collège".

- France Report June 2020 Archived 2021-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, Global Initiative to End all Corporal Punishment of Children.

- "It's 40 years since corporal punishment got a general boot", translated from Saarbrücker Zeitung, 19 June 1987.

- Greece State Report Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC, November 2006.

- "Corporal punishment of children in India" (PDF). Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. July 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- "Corporal punishment against children and the law". The Times of India. 22 February 2019.

- "Teacher suspended over video of beating boy". The Times of India. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- Varandani, Suman (2 November 2021). "15-Year-Old Dies By Suicide After Being Beaten Up By Teacher, Suspended From School". International Business Times. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- Executive regulations for schools approved by the Supreme Council of Education. "Executive regulations for schools approved by the Supreme Council of Education-Meeting 652". Supreme Council of Education. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- Child and Adolescent Protection Law. "Child and Adolescent Protection Law". ekhtebar. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- Child and Adolescent Protection Law. "Child and Adolescent Protection Law". majlis. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

-

- "Children First Bill 2014: Report". Seanad debates. KildareStreet.com. 21 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Primary Branch (January 1982). "R.R. 144329 / Circular 9/82 / Re: The Abolition of Corporal Punishment in National Schools" (PDF). Circulars. Department of Education. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Post-Primary Branch (January 1982). "Circular M5/82 / Abolition of Corporal Punishment in Schools in respect of Financial Aid from the Department of Education" (PDF). Circulars. Department of Education. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

-

- "Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Act, 1997, Section 24". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- "Non-Fatal Offences Against the Person Bill, 1997: Second Stage". Seanad Éireann Debates. 7 May 1997. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

The use of force by teachers, following the enactment of the Bill, will be governed, as in the case of other people, by the rules set out in sections 18 and 19.

- ^ Corporal punishment of children in Israel (PDF) (Report). GITEACPOC. February 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Izenberg, Dan (26 January 2000). "Israel Bans Spanking". The Natural Child Project. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Ezer, Tamar (January 2003). "Children's Rights in Israel: An End to Corporal Punishment?". Oregon Review of International Law. 5: 139. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Italy State Report Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC.

- "Many Japanese Teachers Favor Corporal Punishment". Nichi Bei Times. San Francisco. 21 November 1987.

- "Student commits suicide after being beaten by school basketball coach". Japan Today. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Corporal punishment rife in schools in 2012: survey". The Japan Times. 10 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Country Report for Japan". End Corporal Punishment of Children - End Corporal Punishment of Children End Violence Against Children. End Corporal Punishment. November 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- "Japan prohibits all corporal punishment of children". endcorporalpunishment.org. End Corporal Punishment. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, Report of corporal punishment of children in Luxembourg 2013

- Legilux, Législation sur les mesures de discipline dans les écoles 2015

- Chew, Victor (26 July 2008). "Use the cane only as a last resort, teachers". The Star. Kuala Lumpur. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Girls should be caned too but do it right - Letters". The Star. Kuala Lumpur. 29 November 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Jamil, Syauqi (24 June 2019). "Secondary schoolgirl left with red welts on arms and legs after caning". The Star. Kuala Lumpur. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Girls should be caned too". News24. South Africa. 28 November 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- "Corporal punishment of children in the Republic of Moldova" (PDF). GITEACPOC. June 2020.

- Shwe Gaung, Juliet (26 January 2009). "Corporal punishment 'common practice': author". The Myanmar Times. Yangon. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014.

- Kyaw, Aung (28 June 2004). "Getting the cane". Myanmar Times. Yangon. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Mudditt, Jessica (13 May 2013). "Against the cane: corporal punishment in Myanmar". The Myanmar Times. Yangon. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014.

- Ohmar, Ma (23 April 2002). "Slate & Slate Pencil - Computer & Keyboard". The New Light of Myanmar. Archived from the original on 25 April 2005.

- Ram Kumar Kamat (6 November 2018). "Nepal, first S Asian country to criminalise corporal punishment of children". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu.

- Netherlands State Report Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC.

- "Caning Girls". The Star. Christchurch. 24 February 1890. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "A Sensational School Incident". Evening Post. Wellington. United Press Association. 22 February 1890.

- "Caning a Schoolgirl". New Zealand Herald. Auckland. 19 February 1916. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Caning girls under 12". Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, NSW. 19 June 1930. p. 1. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- Haines, Leah (21 May 2005). "Corporal punishment: stern discipline or abuse?". New Zealand Herald. Auckland. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "The Strap". Radio New Zealand. 29 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Flashback: Corporal punishment in school was lawful until 1990". Stuff. 28 September 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Brown, Russell (31 July 2007). "The cane and the strap • Hard News • Public Address". publicaddress.net. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Long, Jessica (29 September 2016). "Flashback: Corporal punishment in school was lawful until 1990". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "Education Act 1989 - New Zealand Legislation". New Zealand Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- "§202C: Assault with weapon - Crimes Act 1961 No 43 as of 18 April 2012 - New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office (New Zealand). 18 April 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "School in corporal punishment spotlight". Television New Zealand. 18 February 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- Corporal punishment of children in Norway (PDF) (Report). GITEACPOC. June 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- "Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860)". www.pakistani.org.

- ^ George W. Holden, Rose Ashraf. "Children's Right to Safety: The Problem of Corporal Punishment in Pakistan". Child Safety, Welfare and Well-being: Issues and Challenges. p. 69,71.

- "PAKISTAN: Corporal punishment key reason for school dropouts". IRIN Asia. 18 May 2008.

- Philippines State Report Archived 11 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC.

- Abolishing corporal punishment of children : questions and answers (PDF). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. December 2007. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-9-287-16310-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014.

- Newell, Peter (ed.). A Last Resort? Corporal Punishment in Schools, Penguin, London, 1972, p. 9. ISBN 0-14-080698-9

- Article 40th of the Constitution of Poland, 1997,

- Corporal punishment of children in the Russian Federation (PDF) (Report). GITEACPOC. July 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- "Country Report for Serbia". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. June 2020.

- "DCI Sierra Leone urges the Government to prohibit: "all corporal punishment of children"". Defence for Children. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "Sierra Leone | Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children". 20 November 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Vanguard, The Patriotic (4 December 2007). "To hit or not to hit: The use of the cane in schools in Sierra Leone". The Patriotic Vanguard. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "SCHOOL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: Video clip: Sierra Leone". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "WORLD CORPORAL PUNISHMENT WEB LINKS: corporal punishment in schools". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Acting Minister for Education" (Press release). 14 May 2004. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009.

- "Singapore: School caning regulations". World Corporal Punishment Research. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Singapore school handbooks on line. World Corporal Punishment Research.

- Farrell, C. (June 2014). "Singapore: Corporal punishment in schools". World Corporal Punishment Research. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "South African Schools Act, 1996, Chapter 2: Learners, Section 10: Prohibition of corporal punishment". Archived from the original on 27 August 2013.

- "'간접체벌' 시행령에 4개 교육청 거부의사". news.naver.com.

- 진보교육감들 “학생 간접체벌 불허”, 《한겨레》, 2011.3.23

- 학교 체벌 일상화,hankukilbosouth korea,2014.06.27

- "韩国学校体罚大观" (in Chinese (Malaysia)). Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: video clips: schoolgirl canings in South Korea". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "SCHOOL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT IN SOUTH KOREA". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Republic of Korea prohibits all corporal punishment of children". end-violence.org. The Global Partnership and Fund to End Violence Against Children. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- "Republic of Korea prohibits all corporal punishment of children". endcorporalpunishment.org. End Corporal Punishment. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Global Initiative to End Corporal Punishment - Spain State Report Archived 3 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, GITEACPOC.

- "Changing concepts of Grammar School teacher authority in Sweden 1927-1965". Australian Association for Research in Education. 1997.

- "Taiwan corporal punishment banned", BBC News On Line, London, 29 December 2006.

- Ijue sheria ya viboko vya wanafunzi, Mwananchi newspaper 2 September 2018

- "Corporal punishment of children in Thailand" (PDF). GITEACPOC. January 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020.

- "Proverbs | Southeast Asia Program". 19 October 2023.

- "WORLD CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: COUNTRY FILES, INCLUDING REGULATIONS, DESCRIPTIONS AND OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS - page 3: countries T to Z". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "To cane or not to cane?". The ASEAN Post. 29 December 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Beech, Hannah (24 September 2020). "In Thailand, Students Take on the Military (and 'Death Eaters')". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Strict discipline at Thai schools by Richard McCully". www.ajarn.com. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Many Thais favour use of cane for unruly youths: poll". www.asiaone.com. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Leppard, Matt (4 April 2006). "Spare the rod... spoil the child?". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "SCHOOL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: video clips: Thailand 3". World Corporal Punishment Research. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Teacher in hot water for caning students 100 to 300 times". ThaiResidents.com - Thai Local News. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Intathep, Lamphai (5 June 2011). "Video clip prompts caning probe". Bangkok Post. Alt URL

- "男老师爱鞭学生屁股·向女学生索性爱". www.sinchew.com.my. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- "End pupils' fear of teachers' canes (2018)" in D+C Vol. 45 05-06/2018.

- Ukraine. DETAILED COUNTRY REPORT Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Last updated: February 2011.

- http://www.khda.gov.ae/pages/en/commonQuestionssch.aspx Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Corporal punishment ban makes discipline 'almost impossible' say UAE teachers". 9 January 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "UAE teacher banned after forcing child to remove shirt in class". 23 October 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- Ghandhi, Sandy (1984). "Spare the Rod: Corporal Punishment in Schools and the European Convention on Human Rights". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 33 (2): 488–494. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/33.2.488. JSTOR 759074.

- "On this day: 25 February 1982: Parents can stop school beatings". BBC News. 25 February 1982. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Country report for UK". Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children. June 2015.

- Gibson, Ian (1978). The English vice: Beating, sex, and shame in Victorian England and after. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1264-6.

- Blackwood's Magazine. 328. Edinburgh: William Blackwood: 522. 1980. ISSN 0006-436X.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "From the Archive - Caning 'scandal' in London". Tes. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "2 Occasional Paper No 7: Discipline, Rules and Punishments in Schools" (PDF). www.christs-hospital.lincs.sch.uk. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Schools whilst I was at the NCH". www.theirhistory.co.uk. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Kettering, David. "Behave or bend over for the slipper: UK Grammar School life in the 1960s". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Rise and fall of the belt", Sunday Standard, Glasgow, 28 February 1982.

- "Sex discrimination laws prevented ban on the belt for girls, reveal archives". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Ahmed, Kamal (27 April 2003). "He could talk his way out of things". The Observer. London.

- "Parents praise head who admitted caning girl pupils". HeraldScotland. Glasgow. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- "Scottish Review: Carol Craig". www.scottishreview.net. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Jack, Ian (24 March 2018). "I was belted at school. It felt unfair, but was it harmful?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "Scotland on Film - Forum". BBC Scotland. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Guide to LEAs' Corporal Punishment Regulations in England and Wales, Society of Teachers Opposed to Physical Punishment, Croydon, 1979.

- Department of Education, Administrative Memorandum 531, 1956

- Merry, Sam (3 October 1996). "The good old days, eh?". The Independent. London.

- Emmerson, owen (27 October 2017). "No To The Cane". Jacobin. UK.

- "Corporal punishment in British schools, Nov 1971 - CORPUN ARCHIVE uksc7111".

- "School corporal punishment news, UK, Oct 1974 - CORPUN ARCHIVE uksc7410".

- "A History of Corporal Punishment". 14 March 2021.

- Sage, Adam (26 March 1993). "Private schools 'can beat pupils': European Court of Human Rights expresses misgivings on corporal punishment". The Independent. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Ying Hui Tan (26 March 1993). "Law Report: 'Slippering' pupil is not degrading punishment: Costello-Roberts v The United Kingdom. European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg, 25 March 1993". The Independent. London. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "A 'fifth of teachers back caning'". BBC News Online. 3 October 2008.

- Bloom, Adi (10 October 2008). "Survey whips up debate on caning", Times Educational Supplement (London).

- "Country report for USA" (November 2015). 'Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

- Anderson, Melinda D. (15 December 2015). "The States Where Teachers Can Still Spank Students". The Atlantic. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- C. Farrell (October 2016). "Corporal punishment in US schools". www.corpun.com.

- See, e.g., Deana A. Pollard, Banning Corporal Punishment: A Constitutional Analysis, 52 Am. U. L. Rev. 447 (2002); Deana A. Pollard, Banning Child Corporal Punishment, 77 Tul. L. Rev. 575 (2003).

- "Prohibition of all corporal punishment in Venezuela (2007)" Global Initiative to End All Corporal school Punishment of Children.

- "Promoting positive discipline in school". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- Peter Newell, Coordinator, Global Initiative. VIET NAM BRIEFING FOR THE HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW – 5th session, 2008 (PDF) (Report).

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - VnExpress. "Hanoi in shock after teacher beats primary school students for being late - VnExpress International". VnExpress International – Latest news, business, travel and analysis from Vietnam. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "The Heavy Hand". Oi. 12 September 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "SCHOOL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: video clips: Vietnam - caning of schoolgirls". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "SCHOOL CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: video clips: Vietnam - caning of secondary boys and girls". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- "WORLD CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: COUNTRY FILES, INCLUDING REGULATIONS, DESCRIPTIONS AND OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS - page 3: countries T to Z". www.corpun.com. Retrieved 17 November 2019.