This article is about the disease. For the organism, see Echinococcus.

Medical condition

| Echinococcosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hydatid disease, hydatidosis, echinococcal disease, hydatid cyst |

| |

| Echinococcus granulosa life cycle (click to enlarge) | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Variable |

| Causes | Tapeworm of the Echinococcus type |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging, blood tests |

| Prevention | Vaccination of sheep, treating infected dogs |

| Treatment | Conservative, medications, surgery |

| Medication | Albendazole |

| Frequency | 1.4 million (cystic form, 2015) |

| Deaths | 1,200 (cystic form, 2015) |

Echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by tapeworms of the Echinococcus type. The two main types of the disease are cystic echinococcosis and alveolar echinococcosis. Less common forms include polycystic echinococcosis and unicystic echinococcosis.

The disease often starts without symptoms and this may last for years. The symptoms and signs that occur depend on the cyst's location and size. Alveolar disease usually begins in the liver, but can spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs or brain. When the liver is affected, the patient may experience abdominal pain, weight loss, along with yellow-toned skin discoloration from developed jaundice. Lung disease may cause pain in the chest, shortness of breath, and coughing.

The infection is spread when food or water that contains the eggs of the parasite is ingested or by close contact with an infected animal. The eggs are released in the stool of meat-eating animals that are infected by the parasite. Commonly infected animals include dogs, foxes, and wolves. For these animals to become infected they must eat the organs of an animal that contains the cysts such as sheep or rodents. The type of disease that occurs in human patients depends on the type of Echinococcus causing the infection. Diagnosis is usually by ultrasound though computer tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used. Blood tests looking for antibodies against the parasite may be helpful as may biopsy.

Prevention of cystic disease is by treating dogs that may carry the disease and vaccination of sheep. Treatment is often difficult. The cystic disease may be drained through the skin, followed by medication. Sometimes this type of disease is just watched. The alveolar form often requires surgical intervention, followed by medications. The medication used is albendazole, which may be needed for years. The alveolar disease may result in death.

The disease occurs in most areas of the world and currently affects about one million people. In some areas of South America, Africa, and Asia, up to 10% of the certain populations are affected. In 2015, the cystic form caused about 1,200 deaths; down from 2,000 in 1990. The economic cost of the disease is estimated to be around US$3 billion a year. It is classified as a neglected tropical disease (NTD) and belongs to the group of diseases known as helminthiases (worm infections). It can affect other animals such as pigs, cows and horses.

Terminology used in this field is crucial, since echinococcosis requires the involvement of specialists from nearly all disciplines. In 2020, an international effort of scientists, from 16 countries, led to a detailed consensus on terms to be used or rejected for the genetics, epidemiology, biology, immunology, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis.

Signs and symptoms

In the human manifestation of the disease, E. granulosus, E. multilocularis, E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli are localized in the liver (in 75% of cases), the lungs (in 5–15% of cases) and other organs in the body such as the spleen, brain, heart, and kidneys (in 10–20% of cases). In people who are infected with E. granulosus and therefore have cystic echinococcosis, the disease develops as a slow-growing mass in the body. These slow-growing masses, often called cysts, are also found in people that are infected with alveolar and polycystic echinococcosis.

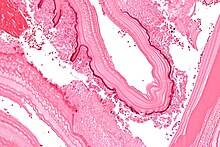

The cysts found in those with cystic echinococcosis are usually filled with a clear fluid called hydatid fluid, are spherical, and typically consist of one compartment and are usually only found in one area of the body. While the cysts found in those with alveolar and polycystic echinococcosis are similar to those found in those with cystic echinococcosis, the alveolar and polycystic echinococcosis cysts usually have multiple compartments and have infiltrative as opposed to expansive growth.

Depending on the location of the cyst in the body, the person could be asymptomatic even though the cysts have grown to be very large, or be symptomatic even if the cysts are absolutely tiny. If the person is symptomatic, the symptoms will depend largely on where the cysts are located. For instance, if the person has cysts in the lungs and is symptomatic, they will have a cough, shortness of breath and/or pain in the chest.

On the other hand, if the person has cysts in the liver and is symptomatic, they will experience abdominal pain, abnormal abdominal tenderness, hepatomegaly with an abdominal mass, jaundice, fever and/or anaphylactic reaction. In addition, if the cysts were to rupture while in the body, whether during surgical extraction of the cysts or by trauma to the body, the person would most likely go into anaphylactic shock and have high fever, pruritus (itching), edema (swelling) of the lips and eyelids, dyspnea, stridor and rhinorrhea.

Unlike intermediate hosts, definitive hosts are usually not hurt very much by the infection. Sometimes, a lack of certain vitamins and minerals can be caused in the host by the very high demand of the parasite.

The incubation period for all species of Echinococcus can be months to years, or even decades. It largely depends on the location of the cyst in the body and how fast the cyst is growing.

Cause

Like many other parasite infections, the course of Echinococcus infection is complex. The worm has a life cycle that requires definitive hosts and intermediate hosts. Definitive hosts are normally carnivores such as dogs, while intermediate hosts are usually herbivores such as sheep and cattle. Humans function as accidental hosts, because they are usually a dead end for the parasitic infection cycle, unless eaten by dogs or wolves after death.

Hosts

| Organism | Definitive Hosts | Intermediate Hosts |

|---|---|---|

| E. granulosus | dogs and other canidae | sheep, goats, cattle, camel, buffalo, swine, kangaroos, and other wild herbivores |

| E. multilocularis | foxes, dogs, other canidae and cats | small rodents |

| E. vogeli | bush dogs and dogs | rodents |

| E. oligarthrus | wild felids | small rodents |

Life cycle

An adult worm resides in the small intestine of a definitive host. A single gravid proglottid releases eggs that are passed in the feces of the definitive host. The egg is then ingested by an intermediate host. The egg then hatches in the small intestine of the intermediate host and releases an oncosphere that penetrates the intestinal wall and moves through the circulatory system into different organs, in particular the liver and lungs. Once it has invaded these organs, the oncosphere develops into a cyst. The cyst then slowly enlarges, creating protoscolices (juvenile scolices), and daughter cysts within the cyst. The definitive host then becomes infected after ingesting the cyst-containing organs of the infected intermediate host. After ingestion, the protoscolices attach to the intestine. They then develop into adult worms and the cycle starts all over again.

Eggs

Echinococcus eggs contain an embryo that is called an oncosphere or hexcanth. The name of this embryo stems from the fact that these embryos have six hooklets. The eggs are passed through the feces of the definitive host and it is the ingestion of these eggs that lead to infection in the intermediate host.

Larval/hydatid cyst stage

From the embryo released from an egg develops a hydatid cyst, which grows to about 5–10 cm within the first year and is able to survive within organs for years. Cysts sometimes grow to be so large that by the end of several years or even decades, they can contain several liters of fluid. Once a cyst has reached a diameter of 1 cm, its wall differentiates into a thick outer, non-cellular membrane, which covers the thin germinal epithelium. From this epithelium, cells begin to grow within the cyst. These cells then become vacuolated, and are known as brood capsules, which are the parts of the parasite from which protoscolices bud. Often, daughter cysts also form within cysts.

Adult worm

Echinococcus adult worms develop from protoscolices and are typically 6 mm or less in length and have a scolex, neck and typically three proglottids, one of which is immature, another of which is mature and the third of which is gravid (or containing eggs). The scolex of the adult worm contains four suckers and a rostellum that has about 25–50 hooks.

Morphological differences

The major morphological difference among different species of Echinococcus is the length of the tapeworm. E. granulosus is approximately 2 to 7 mm while E. multilocularis is often smaller and is 4 mm or less. On the other hand, E. vogeli is found to be up to 5.6 mm long and E. oligarthrus is found to be up to 2.9 mm long. In addition to the difference in length, there are also differences in the hydatid cysts of the different species. For instance, in E. multilocularis, the cysts have an ultra thin limiting membrane and the germinal epithelium may bud externally. Furthermore, E. granulosus cysts are unilocular and full of fluid while E. multilocularis cysts contain little fluid and are multilocular. For E. vogeli, its hydatid cysts are large and are actually polycystic since the germinal membrane of the hydatid cyst actually proliferates both inward, to create septa that divide the hydatid into sections, and outward, to create new cysts. Like E. granulosus cysts, E. vogeli cysts are filled with fluid.

Transmission

As one can see from the life cycles illustrated above, all disease-causing species of Echinococcus are transmitted to intermediate hosts via the ingestion of eggs and are transmitted to definitive hosts by means of eating infected, cyst-containing organs. Humans are accidental intermediate hosts that become infected by handling soil, dirt or animal hair that contains eggs.

While there are no biological or mechanical vectors for the adult or larval form of any Echinococcus species, coprophagic flies, carrion birds and arthropods can act as mechanical vectors for the eggs.

Aberrant cases

There are a few aberrant cases in which carnivores play the role of the intermediate hosts. Examples are domestic cats with hydatid cysts of E. granulosus.

Diagnosis

Classification

The most common form found in humans is cystic echinococcosis (also known as unilocular echinococcosis), which is caused by Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato. The second most common form is alveolar echinococcosis (also known as alveolar colloid of the liver, alveolar hydatid disease, alveolococcosis, multilocular echinococcosis, "small fox tapeworm"), which is caused by Echinococcus multilocularis and the third is polycystic echinococcosis (also known as human polycystic hydatid disease, neotropical echinococcosis), which is caused by Echinococcus vogeli and very rarely, Echinococcus oligarthrus. Alveolar and polycystic echinococcosis are rarely diagnosed in humans and are not as widespread as cystic echinococcosis, but polycystic echinococcosis is relatively new on the medical scene and is often left out of conversations dealing with echinococcosis, and alveolar echinococcosis is a serious disease that has a significantly high fatality rate, and may have the potential to become an emerging disease in many countries.

Cystic

A formal diagnosis of any type of echinococcosis requires a combination of tools that involve imaging techniques, histopathology, or nucleic acid detection and serology. For cystic echinococcosis diagnosis, imaging is the main method—while serology tests (such as indirect hemagglutination, ELISA (enzyme linked immunosorbent assay), immunoblots or latex agglutination) that use antigens specific for E. granulosus verify the imaging results. The imaging technique of choice for cystic echinococcosis is ultrasonography, since it is not only able to visualize the cysts in the body's organs, but it is also inexpensive, non-invasive and gives instant results. In addition to ultrasonography, both MRI and CT scans can and are often used although an MRI is often preferred to CT scans when diagnosing cystic echinococcosis since it gives better visualization of liquid areas within the tissue.

Alveolar

As with cystic echinococcosis, ultrasonography is the imaging technique of choice for alveolar echinococcosis and is usually complemented by CT scans since CT scans are able to detect the largest number of lesions and calcifications that are characteristic of alveolar echinococcosis. MRIs are also used in combination with ultrasonography though CT scans are preferred. Like cystic echinococcosis, imaging is the major method used for the diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis while the same types of serologic tests (except now specific for E. multilocularis antigens) are used to verify the imaging results. It is also important to note that serologic tests are more valuable for the diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis than for cystic echinococcosis since they tend to be more reliable for alveolar echinococcosis since more antigens specific for E. multilocularis are available. In addition to imaging and serology, identification of E. multilocularis infection via PCR or a histological examination of a tissue biopsy from the person is another way to diagnose alveolar echinococcosis.

Polycystic

Similar to the diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis and cystic echinococcosis, the diagnosis of polycystic echinococcosis uses imaging techniques, in particular ultrasonography and CT scans, to detect polycystic structures within the person's body. However, imaging is not the preferred method of diagnosis since the method that is currently considered the standard is the isolation of protoscoleces during surgery or after the person's death and the identification of definitive features of E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli in these isolated protoscoleces. This is the main way that PE is diagnosed, but some current studies show that PCR may identify E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli in people's tissues. The only drawback of using PCR to diagnose polycystic echinococcosis is that there aren't many genetic sequences that can be used for PCR that are specific only E. oligarthrus or E. vogeli.

Prevention

Cystic echinococcosis

There are several different strategies that are currently being used to prevent and control cystic echinococcosis (CE). Most of these various methods try to prevent and control CE by targeting the major risk factors for the disease and the way it is transmitted. For instance, health education programs focused on cystic echinococcosis and its agents, and improved water sanitation attempt to target poor education and poor drinking water sources, which are both risk factors for contracting echinococcosis. Furthermore, since humans often come into contact with Echinococcus eggs via touching contaminated soil, animal feces and animal hair, another prevention strategy is improved hygiene. In addition to targeting risk factors and transmission, control and prevention strategies of cystic echinococcosis also aim at intervening at certain points of the parasite's life cycle, in particular, the infection of hosts (especially dogs) that reside with or near humans. For example, many countries endemic to echinococcosis have researched programs geared at de-worming dogs and vaccinating dogs and other livestock, such as sheep, that also act as hosts for E. granulosus.

Proper disposal of carcasses and offal after home slaughter is difficult in poor and remote communities and therefore dogs readily have access to offal from livestock, thus completing the parasite cycle of Echinococcus granulosus and putting communities at risk of cystic echinococcosis. Boiling livers and lungs that contain hydatid cysts for 30 minutes has been proposed as a simple, efficient and energy- and time-saving way to kill the infectious larvae.

Alveolar echinococcosis

A number of strategies are geared towards prevention and control of alveolar echinococcosis—most of which are similar to those for cystic echinococcosis. For instance, health education programs, improved water sanitation, improved hygiene and de-worming of hosts (particularly red foxes) are all effective to prevent and control the spread of alveolar echinococcosis. Unlike cystic echinococcosis, however, where there is a vaccine against E. granulosus, there is currently no canidae or livestock vaccine against E. multilocularis.

Polycystic echinococcosis

While a number of control and prevention strategies deal with cystic and alveolar echinococcosis, there are few methods to control and prevent polycystic echinococcosis. This is probably due to the fact that polycystic echinococcosis is restricted to Central and South America, and that the way that humans become accidental hosts of E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli is still not completely understood.

Human vaccines

Currently there are no human vaccines against any form of echinococcosis. However, there are studies being conducted that are looking at possible vaccine candidates for an effective human vaccine against echinococcosis.

Treatment

Cystic

A number of therapy options are presently available. Treatment with albendazole, whether combined or not with praziquantel, is useful for smaller, uncomplicated cysts (< 5 cm). Only 30% of cysts disappear with medical treatment alone. Albendazole is preferred twice a day for 1–5 months. An alternative to albendazole is mebendazole for at least 3 to 6 months.

Surgery is indicated for bigger liver cysts (> 10 cm), cysts at risk of rupture and/or complicated cysts. A laparoscopic approach provides excellent cure rates with minimal morbidity and mortality. The radical technique (total cystopericystectomy) is preferable because of its lower risk for postoperative abdominal infection, biliary fistula, and overall morbidity. Conservative techniques are appropriate in endemic areas where surgery is performed by nonspecialist surgeons.

PAIR (puncture-aspiration-injection-reaspiration) is an innovative technique representing an alternative to surgery. PAIR is a minimally invasive procedure that involves three steps: puncture and needle aspiration of the cyst, injection of a scolicidal solution for 20–30 min, and cyst-re-aspiration and final irrigation. People who undergo PAIR typically take albendazole or mebendazole from 7 days before the procedure until 28 days after the procedure. It is indicated for inoperable cases and/or patients who reject surgery, for recurrence after surgery, and for lack of response to medical treatment. There have been a number of studies that suggest that PAIR with medical therapy is more effective than surgery in terms of disease recurrence, and morbidity and mortality.

There is currently research and studies looking at new treatment involving percutaneous thermal ablation (PTA) of the germinal layer in the cyst by means of a radiofrequency ablation device. This form of treatment is still relatively new and requires much more testing before being widely used.

Alveolar

For alveolar echinococcosis, surgical removal of cysts combined with chemotherapy (using albendazole and/or mebendazole) for up to two years after surgery is the only sure way to completely cure the disease. However, in inoperable cases, chemotherapy by itself can also be used. In treatment using just chemotherapy, one could use either mebendazole in three doses or albendazole in two doses. Since chemotherapy on its own is not guaranteed to completely rid of the disease, people are often kept on the drugs for extended periods of times (i.e. more than 6 months, years). In addition to surgery and chemotherapy, liver transplants are being looked into as a form of treatment for alveolar echinococcosis although it is seen as incredibly risky since it often leads to echinococcosis re-infection in the person afterwards.

Polycystic

Since polycystic echinococcosis is constrained to such a particular area of the world and is not well described or found in many people, treatment of polycystic echinococcosis is less defined than that of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. While surgical removal of cysts was the treatment of choice for the previous two types of echinococcosis, chemotherapy is the recommended treatment approach for polycystic echinococcosis. While albendazole is the preferred drug, mebendazole can also be used if the treatment is to be for an extended period of time. Only if chemotherapy fails or if the lesions are very small is surgery advised.

Epidemiology

Regions

Very few countries are considered to be completely free of E. granulosus. Areas of the world where there is a high rate of infection often coincide with rural, grazing areas where dogs are able to ingest organs from infected animals.

E. multilocularis mainly occurs in the Northern hemisphere, including central Europe and the northern parts of Europe, Asia, and North America. However, its distribution was not always like this. For instance, until the end of the 1980s, E. multilocularis endemic areas in Europe were known to exist only in France, Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. But during the 1990s and early 2000s, there was a shift in the distribution of E. multilocularis as the infection rate of foxes escalated in certain parts of France and Germany.

As a result, several new endemic areas were found in Switzerland, Germany, and Austria and surrounding countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Poland, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, and Italy. There is also evidence showing that the Baltic Countries are endemic areas.

While alveolar echinococcosis is not extremely common, it is believed that in the coming years it will be an emerging or re-emerging disease in certain countries as a result of E. multilocularis’ ability to spread.

Unlike the previous two species of Echinococcus, E. vogeli and E. oligarthrus are limited to Central and South America. Furthermore, infections by E. vogeli and E. oligarthrus (polycystic echinococcosis) are considered to be the rarest form of echinococcosis.

Deaths

As of 2010 it caused about 1,200 deaths, down from 2,000 in 1990.

History

Echinococcosis is a disease that has been recognized by humans for centuries. There has been mention of it in the Talmud. It was also recognized by ancient scholars such as Hippocrates, Aretaeus, Galen and Rhazes. The recommended treatments were based on herbs like thymus vulgaris and raw garlic. Although echinococcosis has been well known for the past two thousand years, it was not until the past couple of hundred years that real progress was made in determining and describing its parasitic origin. The first step towards figuring out the cause of echinococcosis occurred during the 17th century when Francesco Redi illustrated that the hydatid cysts of echinococcosis were of "animal" origin. Then, in 1766, Pierre Simon Pallas predicted that these hydatid cysts found in infected humans were actually larval stages of tapeworms.

A few decades afterwards, in 1782, Goeze accurately described the cysts and the tapeworm heads, while in 1786 E. granulosus was accurately described by Batsch. Half a century later, during the 1850s, Karl von Siebold showed through a series of experiments that Echinococcus cysts do cause adult tapeworms in dogs. Shortly after this, in 1863, E. multilocularis was identified by Rudolf Leuckart. Then, during the early to mid 1900s, the more distinct features of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis, their life cycles and how they cause disease were more fully described as more and more people began researching and performing experiments and studies. While E. granulosus and E. multilocularis were both linked to human echinococcosis before or shortly after the 20th century, it was not until the mid-1900s that E. oligarthrus and E. vogeli were identified as and shown as being causes of human echinococcosis.

Two calcified objects recovered from a 3rd- to 4th-century grave of an adolescent in Amiens (Northern France) were interpreted as probable hydatid cysts. A study of remains from two 8,000-year-old cemeteries in Siberia showed presence of echinococcosis.

References

- ^ "Echinococcosis Fact sheet N°377". World Health Organization. March 2014. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Echinococcosis Treatment Information". CDC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. 8 October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. 8 October 2016. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ "Echinococcosis [Echinococcus granulosus] [Echinococcus multilocularis] [Echinococcus oligarthrus] [Echinococcus vogeli]". CDC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ Lozano R (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMC 10790329. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Vuitton DA, McManus DP, Rogan MT, Romig T, Gottstein B, Naidich A, Tuxun T, Wen H, Menezes da Silva A, Vuitton DA, McManus DP, Romig T, Rogan MR, Gottstein B, Menezes da Silva A, Wen H, Naidich A, Tuxun T, Avcioglu A, Boufana B, Budke C, Casulli A, Güven E, Hillenbrand A, Jalousian F, Jemli MH, Knapp J, Laatamna A, Lahmar S, Naidich A, Rogan MT, Sadjjadi SM, Schmidberger J, Amri M, Bellanger AP, Benazzouz S, Brehm K, Hillenbrand A, Jalousian F, Kachani M, Labsi M, Masala G, Menezes da Silva A, Sadjjadi Seyed M, Soufli I, Touil-Boukoffa C, Wang J, Zeyhle E, Aji T, Akhan O, Bresson-Hadni S, Dziri C, Gräter T, Grüner B, Haïf A, Hillenbrand A, Koch S, Rogan MT, Tamarozzi F, Tuxun T, Giraudoux P, Torgerson P, Vizcaychipi K, Xiao N, Altintas N, Lin R, Millon L, Zhang W, Achour K, Fan H, Junghanss T, Mantion GA (2020). "International consensus on terminology to be used in the field of echinococcoses". Parasite. 27: 41. doi:10.1051/parasite/2020024. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 7273836. PMID 32500855.

- Prevention CC (16 July 2019). "CDC - Echinococcosis - Biology". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- "Echinococcosis - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Tappe D, Stich A, Frosch M (February 2008). "Emergence of polycystic neotropical echinococcosis". Emerging Infect. Dis. 14 (2): 292–7. doi:10.3201/eid1402.070742. PMC 2600197. PMID 18258123.

- Canda MS, Canda T, Astarcioglu H, Güray M (2003). "The Pathology of Echinococcosis and the Current Echinococcosis Problem in Western Turkey" (PDF). Turk J Med Sci. 33: 369–374. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2011.

- Eckert J, Deplazes P (2004). "Biological, Epidemiological, and Clinical Aspects of Echinococcosis, a Zoonosis of Increasing Concern - PMC". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 17 (1): 107–135. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.1.107-135.2004. PMC 321468. PMID 14726458.

- "Echinococcosis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Bitton M, Kleiner-Baumgarten A, Peiser J, Barki Y, Sukenik S (February 1992). "Anaphylactic shock after traumatic rupture of a splenic echinococcal cyst". Harefuah (in Hebrew). 122 (4): 226–8. PMID 1563683.

- "Echinococcus". parasite.org.au. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Overstreet RM, Lotz JM (2016). "Host–Symbiont Relationships: Understanding the Change from Guest to Pest". The Rasputin Effect: When Commensals and Symbionts Become Parasitic. Advances in Environmental Microbiology. Vol. 3. pp. 27–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28170-4_2. ISBN 978-3-319-28168-1. PMC 7123458.

- Kemp C, Roberts A (August 2001). "Infectious diseases: echinococcosis (hydatid disease)". Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 13 (8): 346–7. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2001.tb00047.x. PMID 11930567.

- ^ Eckert J, Deplazes P (January 2004). "Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17 (1): 107–35. doi:10.1128/cmr.17.1.107-135.2004. PMC 321468. PMID 14726458.

- Cox FE (2002). "History of Human Parasitology - PMC". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 15 (4): 595–612. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.4.595-612.2002. PMC 126866. PMID 12364371.

- ^ CDC (2010). "Parasites and Health: Echinococcosis". CDC. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- ^ Sréter T, Széll Z, Egyed Z, Varga I (2003). "Echinococcus multilocularis: an Emerging Pathogen in Hungary and Central Eastern Europe". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (3): 384–6. doi:10.3201/eid0903.020320. PMC 2958538. PMID 12643838.

- "Echinococcosis (Dog Tapeworm Infection) - Infections". Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ John DT, William Petri WA, Markell EK, Voge M (January 2006). "7: The Cestodes: Echinococcus granulosus, E. multiloularis and E. vogeli (Hyatid Disease)". Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology (9th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 224–231. ISBN 978-0-7216-4793-7. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. (2010). "Ch. 290". Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (7th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0443068393.

- "Echinococcosis". DPDx. Parasite Image Library. CDC. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- "Echinococcus granulosus". Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS). Public Healthy Agency of Canada. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010.

- Bonelli P, Masu G, Giudici SD, Pintus D, Peruzzu A, Piseddu T, Santucciu C, Cossu A, Demurtas N, Masala G (2018). "Cystic echinococcosis in a domestic cat (Felis catus) in Italy". Parasite. 25: 25. doi:10.1051/parasite/2018027. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 5935470. PMID 29727269.

- Baumann S, Shi R, Liu W, Bao H, Schmidberger J, Kratzer W, Li W, Barth TF, Baumann S, Bloehdorn J, Fischer I, Graeter T, Graf N, Gruener B, Henne-Bruns D, Hillenbrand A, Kaltenbach T, Kern P, Kern P, Klein K, Kratzer W, Ehteshami N, Schlingeloff P, Schmidberger J, Shi R, Staehelin Y, Theis F, Verbitskiy D, Zarour G (1 October 2019). "Worldwide literature on epidemiology of human alveolar echinococcosis: a systematic review of research published in the twenty-first century". Infection. 47 (5): 703–727. doi:10.1007/s15010-019-01325-2. PMC 8505309. PMID 31147846 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA (April 2010). "Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans". Acta Trop. 114 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001. PMID 19931502.

- Macpherson CN, Milner R (February 2003). "Performance characteristics and quality control of community based ultrasound surveys for cystic and alveolar echinococcosis". Acta Trop. 85 (2): 203–9. doi:10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00224-3. PMID 12606098.

- Rizi FR. "Hydatid cyst | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. doi:10.53347/rid-152545. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- Knapp J, Chirica M, Simonnet C, et al. (December 2009). "Echinococcus vogeli infection in a hunter, French Guiana". Emerging Infect. Dis. 15 (12): 2029–31. doi:10.3201/eid1512.090940. PMC 3044547. PMID 19961693.

- ^ Li J, Wu C, Wang H, Liu H, Vuitton DA, Wen H, Zhang W (2014). "Boiling sheep liver or lung for 30 minutes is necessary and sufficient to kill Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces in hydatid cysts". Parasite. 21: 64. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014064. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 4251422. PMID 25456565.

- Lightowlers MW, Heath DD (5 June 2004). "Immunity and vaccine control of Echinococcus granulosus infection in animal intermediate hosts". Parassitologia. 46 (1–2): 27–31. PMID 15305682. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2022 – via PubMed.

- Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, et al. (June 2007). "Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis". Lancet Infect Dis. 7 (6): 385–94. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70134-2. PMID 17521591.

- Dang Z, Yagi K, Oku Y, et al. (December 2009). "Evaluation of Echinococcus multilocularis tetraspanins as vaccine candidates against primary alveolar echinococcosis". Vaccine. 27 (52): 7339–45. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.539.7799. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.045. PMID 19782112.

- ^ Ferrer Inaebnit E, Molina Romero FX, Segura Sampedro JJ, González Argenté X, Morón Canis JM (January 2022). "A review of the diagnosis and management of liver hydatid cyst". Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas. 114 (1): 35–41. doi:10.17235/reed.2021.7896/2021. ISSN 1130-0108. PMID 34034501. S2CID 235200924.

- ^ "The Medical Letter (Drugs for Parasitic Infections)" (PDF). DPDx, CDC. 20 July 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2010.

- Jani K (July 2014). "Spillage-free laparoscopic management of hepatic hydatid disease using the hydatid trocar canula". J Minim Access Surg. 10 (3): 113–8. doi:10.4103/0972-9941.134873. PMC 4083542. PMID 25013326.

- "PAIR: Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re-aspiration An option for the treatment of cystic echinococcosis". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Park KH, Jung SI, Jang HC, Shin JH (October 2009). "First successful puncture, aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration of hydatid cyst in the liver presenting with anaphylactic shock in Korea". Yonsei Med. J. 50 (5): 717–20. doi:10.3349/ymj.2009.50.5.717. PMC 2768250. PMID 19881979.

- Budke CM, Deplazes P, Torgerson PR (February 2006). "Global socioeconomic impact of cystic echinococcosis". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (2): 296–303. doi:10.3201/eid1202.050499. PMC 3373106. PMID 16494758.

- Gessese AT (2020). "Review on Epidemiology and Public Health Significance of Hydatidosis - PMC". Veterinary Medicine International. 2020: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2020/8859116. PMC 7735834. PMID 33354312.

- Massolo A, Liccioli S, Budke C, Klein C (2014). "Echinococcus multilocularis in North America: the great unknown". Parasite. 21: 73. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014069. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 4273702. PMID 25531581.

- Cerda JR, Buttke DE, Ballweber LR (2018). "Echinococcus spp. Tapeworms in North America - PMC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 24 (2): 230–235. doi:10.3201/eid2402.161126. PMC 5782903. PMID 29350139.

- Lassen B, Janson M, Viltrop A, Neare K, Hütt P, Golovljova I, Tummeleht L, Jokelainen P (2016). "Serological Evidence of Exposure to Globally Relevant Zoonotic Parasites in the Estonian Population". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0164142. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1164142L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164142. PMC 5056716. PMID 27723790.

- Marcinkutė A, Moks E, Saarma U, Jokelainen P, Bagrade G, Laivacuma S, Strupas K, Sokolovas V, Deplazes P (2015). "Echinococcus infections in the Baltic region". Vet Par. 213 (3–4): 121–31. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.07.032. PMID 26324242.

- Wen H, Vuitton L, Tuxun T, Li J, Vuitton DA, Zhang W, McManus DP (2019). "Echinococcosis: Advances in the 21st Century - PMC". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 32 (2): e00075-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00075-18. PMC 6431127. PMID 30760475.

- ^ Mowlavi G, Kacki S, Dupouy-Camet J, Mobedi I, Makki M, Harandi M, Naddaf S (2014). "Probable hepatic capillariosis and hydatidosis in an adolescent from the late Roman period buried in Amiens (France)". Parasite. 21. Article no. 9. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014010. PMC 3936287. PMID 24572211.

- "tapeworms: Topics by Science.gov". www.science.gov. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Egerton FN (5 October 2008). "A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 30: Invertebrate Zoology and Parasitology During the 1700s". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 89 (4): 407–433. doi:10.1890/0012-9623(2008)89[407:AHOTES]2.0.CO;2.

- Howorth MB (July 1945). "Echinococcosis Of Bone". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 27 (3): 401–411. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016.

- Connolly S (2006). "Echinococcosis". Archived from the original on 10 December 2008.

- Viegas, Jennifer "Dogs Were a Prehistoric Woman's Best Friend, Too" Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Discovery Communications, 17 July 2014. Retrieved on 25 November 2014.

Further reading

- Alimuddin I. Zumla, Gordon C. Cook, Patrick Manson (2003). "Section 10: Helminthic Infections 83. Echinococcosis/Hydatidosis". Manson's tropical diseases. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7020-2640-9.

- Vuitton DA, Millon L, Gottstein B, Giraudoux P (2014). "Proceedings of the international symposium — innovation for the management of echinococcosis. Besançon, March 27–29, 2014". Parasite. 21: 28. doi:10.1051/parasite/2014024. PMC 4071351.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |