Medical condition

| Carbon monoxide poisoning | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Carbon monoxide intoxication, carbon monoxide toxicity, carbon monoxide overdose |

| |

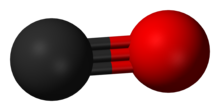

| Carbon monoxide | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, confusion |

| Complications | Loss of consciousness, arrhythmias, seizures |

| Causes | Breathing in carbon monoxide |

| Diagnostic method | Carboxyhemoglobin level: 3% (nonsmokers) 10% (smokers) |

| Differential diagnosis | Cyanide toxicity, alcoholic ketoacidosis, aspirin poisoning, upper respiratory tract infection |

| Prevention | Carbon monoxide detectors, venting of gas appliances, maintenance of exhaust systems |

| Treatment | Supportive care, 100% oxygen, hyperbaric oxygen therapy |

| Prognosis | Risk of death: 1–31% |

| Frequency | >20,000 emergency visits for non-fire related cases per year (US) |

| Deaths | >400 non-fire related a year (US) |

Carbon monoxide poisoning typically occurs from breathing in carbon monoxide (CO) at excessive levels. Symptoms are often described as "flu-like" and commonly include headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, and confusion. Large exposures can result in loss of consciousness, arrhythmias, seizures, or death. The classically described "cherry red skin" rarely occurs. Long-term complications may include chronic fatigue, trouble with memory, and movement problems.

CO is a colorless and odorless gas which is initially non-irritating. It is produced during incomplete burning of organic matter. This can occur from motor vehicles, heaters, or cooking equipment that run on carbon-based fuels. Carbon monoxide primarily causes adverse effects by combining with hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin (symbol COHb or HbCO) preventing the blood from carrying oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide as carbaminohemoglobin. Additionally, many other hemoproteins such as myoglobin, Cytochrome P450, and mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase are affected, along with other metallic and non-metallic cellular targets.

Diagnosis is typically based on a HbCO level of more than 3% among nonsmokers and more than 10% among smokers. The biological threshold for carboxyhemoglobin tolerance is typically accepted to be 15% COHb, meaning toxicity is consistently observed at levels in excess of this concentration. The FDA has previously set a threshold of 14% COHb in certain clinical trials evaluating the therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide. In general, 30% COHb is considered severe carbon monoxide poisoning. The highest reported non-fatal carboxyhemoglobin level was 73% COHb.

Efforts to prevent poisoning include carbon monoxide detectors, proper venting of gas appliances, keeping chimneys clean, and keeping exhaust systems of vehicles in good repair. Treatment of poisoning generally consists of giving 100% oxygen along with supportive care. This procedure is often carried out until symptoms are absent and the HbCO level is less than 3%/10%.

Carbon monoxide poisoning is relatively common, resulting in more than 20,000 emergency room visits a year in the United States. It is the most common type of fatal poisoning in many countries. In the United States, non-fire related cases result in more than 400 deaths a year. Poisonings occur more often in the winter, particularly from the use of portable generators during power outages. The toxic effects of CO have been known since ancient history. The discovery that hemoglobin is affected by CO emerged with an investigation by James Watt and Thomas Beddoes into the therapeutic potential of hydrocarbonate in 1793, and later confirmed by Claude Bernard between 1846 and 1857.

Background

Carbon monoxide is not toxic to all forms of life, and the toxicity is a classical dose-dependent example of hormesis. Small amounts of carbon monoxide are naturally produced through many enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions across phylogenetic kingdoms where it can serve as an important neurotransmitter (subcategorized as a gasotransmitter) and a potential therapeutic agent. In the case of prokaryotes, some bacteria produce, consume and respond to carbon monoxide whereas certain other microbes are susceptible to its toxicity. Currently, there are no known adverse effects on photosynthesizing plants.

The harmful effects of carbon monoxide are generally considered to be due to tightly binding with the prosthetic heme moiety of hemoproteins that results in interference with cellular operations, for example: carbon monoxide binds with hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin which affects gas exchange and cellular respiration. Inhaling excessive concentrations of the gas can lead to hypoxic injury, nervous system damage, and even death.

As pioneered by Esther Killick, different species and different people across diverse demographics may have different carbon monoxide tolerance levels. The carbon monoxide tolerance level for any person is altered by several factors, including genetics (hemoglobin mutations), behavior such as activity level, rate of ventilation, a pre-existing cerebral or cardiovascular disease, cardiac output, anemia, sickle cell disease and other hematological disorders, geography and barometric pressure, and metabolic rate.

Physiology

Main article: GasotransmittersCarbon monoxide is produced naturally by many physiologically relevant enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions best exemplified by heme oxygenase catalyzing the biotransformation of heme (an iron protoporphyrin) into biliverdin and eventually bilirubin. Aside from physiological signaling, most carbon monoxide is stored as carboxyhemoglobin at non-toxic levels below 3% HbCO.

Therapeutics

Small amounts of CO are beneficial and enzymes exist that produce it at times of oxidative stress. A variety of drugs are being developed to introduce small amounts of CO, these drugs are commonly called carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. Historically, the therapeutic potential of factitious airs, notably carbon monoxide as hydrocarbonate, was investigated by Thomas Beddoes, James Watt, Tiberius Cavallo, James Lind, Humphry Davy, and others in many labs such as the Pneumatic Institution.

Signs and symptoms

On average, exposures at 100 ppm or greater is dangerous to human health. The WHO recommended levels of indoor CO exposure in 24 hours is 4 mg/m. Acute exposure should not exceed 10 mg/m in 8 hours, 35 mg/m in one hour and 100 mg/m in 15 minutes.

| Concentration | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 35 ppm (0.0035%), (0.035‰) | Headache and dizziness within six to eight hours of constant exposure |

| 100 ppm (0.01%), (0.1‰) | Slight headache in two to three hours |

| 200 ppm (0.02%), (0.2‰) | Slight headache within two to three hours; loss of judgment |

| 400 ppm (0.04%), (0.4‰) | Frontal headache within one to two hours |

| 800 ppm (0.08%), (0.8‰) | Dizziness, nausea, and convulsions within 45 min; insensible within 2 hours |

| 1,600 ppm (0.16%), (1.6‰) | Headache, increased heart rate, dizziness, and nausea within 20 min; death in less than 2 hours |

| 3,200 ppm (0.32%), (3.2‰) | Headache, dizziness and nausea in five to ten minutes. Death within 30 minutes. |

| 6,400 ppm (0.64%), (6.4‰) | Headache and dizziness in one to two minutes. Convulsions, respiratory arrest, and death in less than 20 minutes. |

| 12,800 ppm (1.28%), (12.8‰) | Unconsciousness after 2–3 breaths. Death in less than three minutes. |

Acute poisoning

The main manifestations of carbon monoxide poisoning develop in the organ systems most dependent on oxygen use, the central nervous system and the heart. The initial symptoms of acute carbon monoxide poisoning include headache, nausea, malaise, and fatigue. These symptoms are often mistaken for a virus such as influenza or other illnesses such as food poisoning or gastroenteritis. Headache is the most common symptom of acute carbon monoxide poisoning; it is often described as dull, frontal, and continuous. Increasing exposure produces cardiac abnormalities including fast heart rate, low blood pressure, and cardiac arrhythmia; central nervous system symptoms include delirium, hallucinations, dizziness, unsteady gait, confusion, seizures, central nervous system depression, unconsciousness, respiratory arrest, and death. Less common symptoms of acute carbon monoxide poisoning include myocardial ischemia, atrial fibrillation, pneumonia, pulmonary edema, high blood sugar, lactic acidosis, muscle necrosis, acute kidney failure, skin lesions, and visual and auditory problems. Carbon monoxide exposure may lead to a significantly shorter life span due to heart damage.

One of the major concerns following acute carbon monoxide poisoning is the severe delayed neurological manifestations that may occur. Problems may include difficulty with higher intellectual functions, short-term memory loss, dementia, amnesia, psychosis, irritability, a strange gait, speech disturbances, Parkinson's disease-like syndromes, cortical blindness, and a depressed mood. Depression may occur in those who did not have pre-existing depression. These delayed neurological sequelae may occur in up to 50% of poisoned people after 2 to 40 days. It is difficult to predict who will develop delayed sequelae; however, advanced age, loss of consciousness while poisoned, and initial neurological abnormalities may increase the chance of developing delayed symptoms.

Chronic poisoning

Chronic exposure to relatively low levels of carbon monoxide may cause persistent headaches, lightheadedness, depression, confusion, memory loss, nausea, hearing disorders and vomiting. It is unknown whether low-level chronic exposure may cause permanent neurological damage. Typically, upon removal from exposure to carbon monoxide, symptoms usually resolve themselves, unless there has been an episode of severe acute poisoning. However, one case noted permanent memory loss and learning problems after a three-year exposure to relatively low levels of carbon monoxide from a faulty furnace.

Chronic exposure may worsen cardiovascular symptoms in some people. Chronic carbon monoxide exposure might increase the risk of developing atherosclerosis. Long-term exposures to carbon monoxide present the greatest risk to persons with coronary heart disease and in females who are pregnant.

In experimental animals, carbon monoxide appears to worsen noise-induced hearing loss at noise exposure conditions that would have limited effects on hearing otherwise. In humans, hearing loss has been reported following carbon monoxide poisoning. Unlike the findings in animal studies, noise exposure was not a necessary factor for the auditory problems to occur.

Fatal poisoning

One classic sign of carbon monoxide poisoning is more often seen in the dead rather than the living – people have been described as looking red-cheeked and healthy. However, since this "cherry-red" appearance is more common in the dead, it is not considered a useful diagnostic sign in clinical medicine. In autopsy examinations, the appearance of carbon monoxide poisoning is notable because unembalmed dead persons are normally bluish and pale, whereas dead carbon-monoxide poisoned people may appear unusually lifelike in coloration. The colorant effect of carbon monoxide in such postmortem circumstances is thus analogous to its use as a red colorant in the commercial meat-packing industry.

Epidemiology

The true number of cases of carbon monoxide poisoning is unknown, since many non-lethal exposures go undetected. From the available data, carbon monoxide poisoning is the most common cause of injury and death due to poisoning worldwide. Poisoning is typically more common during the winter months. This is due to increased domestic use of gas furnaces, gas or kerosene space heaters, and kitchen stoves during the winter months, which if faulty and/or used without adequate ventilation, may produce excessive carbon monoxide. Carbon monoxide detection and poisoning also increases during power outages, when electric heating and cooking appliances become inoperative and residents may temporarily resort to fuel-burning space heaters, stoves, and grills (some of which are safe only for outdoor use but nonetheless are errantly burned indoors).

It has been estimated that more than 40,000 people per year seek medical attention for carbon monoxide poisoning in the United States. 95% of carbon monoxide poisoning deaths in Australia are due to gas space heaters. In many industrialized countries, carbon monoxide is the cause of more than 50% of fatal poisonings. In the United States, approximately 200 people die each year from carbon monoxide poisoning associated with home fuel-burning heating equipment. Carbon monoxide poisoning contributes to the approximately 5,613 smoke inhalation deaths each year in the United States. The CDC reports, "Each year, more than 500 Americans die from unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning, and more than 2,000 commit suicide by intentionally poisoning themselves." For the 10-year period from 1979 to 1988, 56,133 deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning occurred in the United States, with 25,889 of those being suicides, leaving 30,244 unintentional deaths. A report from New Zealand showed that 206 people died from carbon monoxide poisoning in the years of 2001 and 2002. In total carbon monoxide poisoning was responsible for 43.9% of deaths by poisoning in that country. In South Korea, 1,950 people had been poisoned by carbon monoxide with 254 deaths from 2001 through 2003. A report from Jerusalem showed 3.53 per 100,000 people were poisoned annually from 2001 through 2006. In Hubei, China, 218 deaths from poisoning were reported over a 10-year period with 16.5% being from carbon monoxide exposure.

Causes

| Concentration | Source |

|---|---|

| 0.1 ppm | Natural atmosphere level (MOPITT) |

| 0.5 to 5 ppm | Average level in homes |

| 5 to 15 ppm | Near properly adjusted gas stoves in homes |

| 100 to 200 ppm | Exhaust from automobiles in the Mexico City central area |

| 5,000 ppm | Exhaust from a home wood fire |

| 7,000 ppm | Undiluted warm car exhaust without a catalytic converter |

| 30,000 ppm | Afterdamp following an explosion in a coal mine |

Carbon monoxide is a product of combustion of organic matter under conditions of restricted oxygen supply, which prevents complete oxidation to carbon dioxide (CO2). Sources of carbon monoxide include cigarette smoke, house fires, faulty furnaces, heaters, wood-burning stoves, internal combustion vehicle exhaust, electrical generators, propane-fueled equipment such as portable stoves, and gasoline-powered tools such as leaf blowers, lawn mowers, high-pressure washers, concrete cutting saws, power trowels, and welders. Exposure typically occurs when equipment is used in buildings or semi-enclosed spaces.

Riding in the back of pickup trucks has led to poisoning in children. Idling automobiles with the exhaust pipe blocked by snow has led to the poisoning of car occupants. Any perforation between the exhaust manifold and shroud can result in exhaust gases reaching the cabin. Generators and propulsion engines on boats, especially houseboats, has resulted in fatal carbon monoxide exposures.

Poisoning may also occur following the use of a self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA) due to faulty diving air compressors.

In caves carbon monoxide can build up in enclosed chambers due to the presence of decomposing organic matter. In coal mines incomplete combustion may occur during explosions resulting in the production of afterdamp. The gas is up to 3% CO and may be fatal after just a single breath. Following an explosion in a colliery, adjacent interconnected mines may become dangerous due to the afterdamp leaking from mine to mine. Such an incident followed the Trimdon Grange explosion which killed men in the Kelloe mine.

Another source of poisoning is exposure to the organic solvent dichloromethane, also known as methylene chloride, found in some paint strippers, as the metabolism of dichloromethane produces carbon monoxide. In November 2019, an EPA ban on dichloromethane in paint strippers for consumer use took effect in the United States.

Prevention

Detectors

Prevention remains a vital public health issue, requiring public education on the safe operation of appliances, heaters, fireplaces, and internal-combustion engines, as well as increased emphasis on the installation of carbon monoxide detectors. Carbon monoxide is tasteless, odourless, and colourless, and therefore can not be detected by visual cues or smell.

The United States Consumer Product Safety Commission has stated, "carbon monoxide detectors are as important to home safety as smoke detectors are," and recommends each home have at least one carbon monoxide detector, and preferably one on each level of the building. These devices, which are relatively inexpensive and widely available, are either battery- or AC-powered, with or without battery backup. In buildings, carbon monoxide detectors are usually installed around heaters and other equipment. If a relatively high level of carbon monoxide is detected, the device sounds an alarm, giving people the chance to evacuate and ventilate the building. Unlike smoke detectors, carbon monoxide detectors do not need to be placed near ceiling level.

The use of carbon monoxide detectors has been standardized in many areas. In the US, NFPA 720–2009, the carbon monoxide detector guidelines published by the National Fire Protection Association, mandates the placement of carbon monoxide detectors/alarms on every level of the residence, including the basement, in addition to outside sleeping areas. In new homes, AC-powered detectors must have battery backup and be interconnected to ensure early warning of occupants at all levels. NFPA 720-2009 is the first national carbon monoxide standard to address devices in non-residential buildings. These guidelines, which now pertain to schools, healthcare centers, nursing homes, and other non-residential buildings, include three main points:

- 1. A secondary power supply (battery backup) must operate all carbon monoxide notification appliances for at least 12 hours,

- 2. Detectors must be on the ceiling in the same room as permanently installed fuel-burning appliances, and

- 3. Detectors must be located on every habitable level and in every HVAC zone of the building.

Gas organizations will often recommend getting gas appliances serviced at least once a year.

Legal requirements

The NFPA standard is not necessarily enforced by law. As of April 2006, the US state of Massachusetts requires detectors to be present in all residences with potential CO sources, regardless of building age and whether they are owner-occupied or rented. This is enforced by municipal inspectors and was inspired by the death of 7-year-old Nicole Garofalo in 2005 due to snow blocking a home heating vent. Other jurisdictions may have no requirement or only mandate detectors for new construction or at time of sale.

World Health Organization recommendations

The following guideline values (ppm values rounded) and periods of time-weighted average exposures have been determined in such a way that the carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level of 2.5% is not exceeded, even when a normal subject engages in light or moderate exercise:

- 100 mg/m (87 ppm) for 15 min

- 60 mg/m (52 ppm) for 30 min

- 30 mg/m (26 ppm) for 1 h

- 10 mg/m (9 ppm) for 8 h

- 7 mg/m (6 ppm) for 24 h (for indoor air quality, so as not to exceed 2% COHb for chronic exposure)

Diagnosis

As many symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning also occur with many other types of poisonings and infections (such as the flu), the diagnosis is often difficult. A history of potential carbon monoxide exposure, such as being exposed to a residential fire, may suggest poisoning, but the diagnosis is confirmed by measuring the levels of carbon monoxide in the blood. This can be determined by measuring the amount of carboxyhemoglobin compared to the amount of hemoglobin in the blood.

The ratio of carboxyhemoglobin to hemoglobin molecules in an average person may be up to 5%, although cigarette smokers who smoke two packs per day may have levels up to 9%. In symptomatic poisoned people they are often in the 10–30% range, while persons who die may have postmortem blood levels of 30–90%.

As people may continue to experience significant symptoms of CO poisoning long after their blood carboxyhemoglobin concentration has returned to normal, presenting to examination with a normal carboxyhemoglobin level (which may happen in late states of poisoning) does not rule out poisoning.

Measuring

Carbon monoxide may be quantitated in blood using spectrophotometric methods or chromatographic techniques in order to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in a person or to assist in the forensic investigation of a case of fatal exposure.

A CO-oximeter can be used to determine carboxyhemoglobin levels. Pulse CO-oximeters estimate carboxyhemoglobin with a non-invasive finger clip similar to a pulse oximeter. These devices function by passing various wavelengths of light through the fingertip and measuring the light absorption of the different types of hemoglobin in the capillaries. The use of a regular pulse oximeter is not effective in the diagnosis of carbon monoxide poisoning as these devices may be unable to distinguish carboxyhemoglobin from oxyhemoglobin. Breath CO monitoring offers an alternative to pulse CO-oximetry. Carboxyhemoglobin levels have been shown to have a strong correlation with breath CO concentration. However, many of these devices require the user to inhale deeply and hold their breath to allow the CO in the blood to escape into the lung before the measurement can be made. As this is not possible in people who are unresponsive, these devices may not appropriate for use in on-scene emergency care detection of CO poisoning.

Differential diagnosis

There are many conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis of carbon monoxide poisoning. The earliest symptoms, especially from low level exposures, are often non-specific and readily confused with other illnesses, typically flu-like viral syndromes, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome, chest pain, and migraine or other headaches. Carbon monoxide has been called a "great mimicker" due to the presentation of poisoning being diverse and nonspecific. Other conditions included in the differential diagnosis include acute respiratory distress syndrome, altitude sickness, lactic acidosis, diabetic ketoacidosis, meningitis, methemoglobinemia, or opioid or toxic alcohol poisoning.

Treatment

| Oxygen pressure О2 | Time |

|---|---|

| 21% oxygen at normal atmospheric pressure (fresh air) | 5 hours 20 min |

| 100% oxygen at normal atmospheric pressure (non-rebreather oxygen mask) | 1 hours 20 min |

| 100% hyperbaric oxygen (3 atmospheres absolute) | 23 min |

Initial treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning is to immediately remove the person from the exposure without endangering further people. Those who are unconscious may require CPR on site. Administering oxygen via non-rebreather mask shortens the half-life of carbon monoxide from 320 minutes, when breathing normal air, to only 80 minutes. Oxygen hastens the dissociation of carbon monoxide from carboxyhemoglobin, thus turning it back into hemoglobin. Due to the possible severe effects in the baby, pregnant women are treated with oxygen for longer periods of time than non-pregnant people.

Hyperbaric oxygen

Hyperbaric oxygen is also used in the treatment of carbon monoxide poisoning, as it may hasten dissociation of CO from carboxyhemoglobin and cytochrome oxidase to a greater extent than normal oxygen. Hyperbaric oxygen at three times atmospheric pressure reduces the half life of carbon monoxide to 23 minutes, compared to 80 minutes for oxygen at regular atmospheric pressure. It may also enhance oxygen transport to the tissues by plasma, partially bypassing the normal transfer through hemoglobin. However, it is controversial whether hyperbaric oxygen actually offers any extra benefits over normal high flow oxygen, in terms of increased survival or improved long-term outcomes. There have been randomized controlled trials in which the two treatment options have been compared; of the six performed, four found hyperbaric oxygen improved outcome and two found no benefit for hyperbaric oxygen. Some of these trials have been criticized for apparent flaws in their implementation. A review of all the literature concluded that the role of hyperbaric oxygen is unclear and the available evidence neither confirms nor denies a medically meaningful benefit. The authors suggested a large, well designed, externally audited, multicentre trial to compare normal oxygen with hyperbaric oxygen. While hyperbaric oxygen therapy is used for severe poisonings, the benefit over standard oxygen delivery is unclear.

Other

Further treatment for other complications such as seizure, hypotension, cardiac abnormalities, pulmonary edema, and acidosis may be required. Hypotension requires treatment with intravenous fluids; vasopressors may be required to treat myocardial depression. Cardiac dysrhythmias are treated with standard advanced cardiac life support protocols. If severe, metabolic acidosis is treated with sodium bicarbonate. Treatment with sodium bicarbonate is controversial as acidosis may increase tissue oxygen availability. Treatment of acidosis may only need to consist of oxygen therapy. The delayed development of neuropsychiatric impairment is one of the most serious complications of carbon monoxide poisoning. Brain damage is confirmed following MRI or CAT scans. Extensive follow up and supportive treatment is often required for delayed neurological damage. Outcomes are often difficult to predict following poisoning, especially people who have symptoms of cardiac arrest, coma, metabolic acidosis, or have high carboxyhemoglobin levels. One study reported that approximately 30% of people with severe carbon monoxide poisoning will have a fatal outcome. It has been reported that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may increase the likelihood of delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae (DNS) after carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning. A device that also provides some carbon dioxide to stimulate faster breathing (sold under the brand name ClearMate) may also be used.

Pathophysiology

The precise mechanisms by which the effects of carbon monoxide are induced upon bodily systems are complex and not yet fully understood. Known mechanisms include carbon monoxide binding to hemoglobin, myoglobin and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase and restricting oxygen supply, and carbon monoxide causing brain lipid peroxidation.

Hemoglobin

Main article: CarboxyhemoglobinCarbon monoxide has a higher diffusion coefficient compared to oxygen, and the main enzyme in the human body that produces carbon monoxide is heme oxygenase, which is located in nearly all cells and platelets. Most endogenously produced CO is stored bound to hemoglobin as carboxyhemoglobin. The simplistic understanding for the mechanism of carbon monoxide toxicity is based on excess carboxyhemoglobin decreasing the oxygen-delivery capacity of the blood to tissues throughout the body. In humans, the affinity between hemoglobin and carbon monoxide is approximately 240 times stronger than the affinity between hemoglobin and oxygen. However, certain mutations such as the Hb-Kirklareli mutation has a relative 80,000 times greater affinity for carbon monoxide than oxygen resulting in systemic carboxyhemoglobin reaching a sustained level of 16% COHb.

Hemoglobin is a tetramer with four prosthetic heme groups to serve as oxygen binding sites. The average red blood cell contains 250 million hemoglobin molecules, therefore 1 billion heme sites capable of binding gas. The binding of carbon monoxide at any one of these sites increases the oxygen affinity of the remaining three sites, which causes the hemoglobin molecule to retain oxygen that would otherwise be delivered to the tissue; therefore carbon monoxide binding at any site may be as dangerous as carbon monoxide binding to all sites. Delivery of oxygen is largely driven by the Bohr effect and Haldane effect. To provide a simplified synopsis of the molecular mechanism of systemic gas exchange in layman's terms, upon inhalation of air it was widely thought oxygen binding to any of the heme sites triggers a conformational change in the globin/protein unit of hemoglobin which then enables the binding of additional oxygen to each of the other vacant heme sites. Upon arrival to the cell/tissues, oxygen release into the tissue is driven by "acidification" of the local pH (meaning a relatively higher concentration of 'acidic' protons/hydrogen ions) caused by an increase in the biotransformation of carbon dioxide waste into carbonic acid via carbonic anhydrase. In other words, oxygenated arterial blood arrives at cells in the "hemoglobin R-state" which has deprotonated/unionized amino acid residues (regarding nitrogen/amines) due to the less-acidic arterial pH environment (arterial blood averages pH 7.407 whereas venous blood is slightly more acidic at pH 7.371). The "T-state" of hemoglobin is deoxygenated in venous blood partially due to protonation/ionization caused by the acidic environment hence causing a conformation unsuited for oxygen-binding (in other words, oxygen is 'ejected' upon arrival to the cell because acid "attacks" the amines of hemoglobin causing ionization/protonation of the amine residues resulting in a conformation change unsuited for retaining oxygen). Furthermore, the mechanism for formation of carbaminohemoglobin generates additional 'acidic' hydrogen ions that may further stabilize the protonated/ionized deoxygenated hemoglobin. Upon return of venous blood into the lung and subsequent exhalation of carbon dioxide, the blood is "de-acidified" (see also: hyperventilation) allowing for the deprotonation/unionization of hemoglobin to then re-enable oxygen-binding as part of the transition to arterial blood (note this process is complex due to involvement of chemoreceptors and other physiological functionalities). Carbon monoxide is not 'ejected' due to acid, therefore carbon monoxide poisoning disturbs this physiological process hence the venous blood of poisoning patients is bright red akin to arterial blood since the carbonyl/carbon monoxide is retained. Hemoglobin is dark in deoxygenated venous blood, but it has a bright red color when carrying blood in oxygenated arterial blood and when converted into carboxyhemoglobin in both arterial and venous blood, so poisoned cadavers and even commercial meats treated with carbon monoxide acquire an unnatural lively reddish hue.

At toxic concentrations, carbon monoxide as carboxyhemoglobin significantly interferes with respiration and gas exchange by simultaneously inhibiting acquisition and delivery of oxygen to cells and preventing formation of carbaminohemoglobin which accounts for approximately 30% of carbon dioxide exportation. Therefore, a patient with carbon monoxide poisoning may experience severe hypoxia and acidosis (potentially both respiratory acidosis and metabolic acidosis) in addition to the toxicities of excess carbon monoxide inhibiting numerous hemoproteins, metallic and non-metallic targets which affect cellular machinery.

Myoglobin

Carbon monoxide also binds to the hemeprotein myoglobin. It has a high affinity for myoglobin, about 60 times greater than that of oxygen. Carbon monoxide bound to myoglobin may impair its ability to utilize oxygen. This causes reduced cardiac output and hypotension, which may result in brain ischemia. A delayed return of symptoms have been reported. This results following a recurrence of increased carboxyhemoglobin levels; this effect may be due to a late release of carbon monoxide from myoglobin, which subsequently binds to hemoglobin.

Cytochrome oxidase

Another mechanism involves effects on the mitochondrial respiratory enzyme chain that is responsible for effective tissue utilization of oxygen. Carbon monoxide binds to cytochrome oxidase with less affinity than oxygen, so it is possible that it requires significant intracellular hypoxia before binding. This binding interferes with aerobic metabolism and efficient adenosine triphosphate synthesis. Cells respond by switching to anaerobic metabolism, causing anoxia, lactic acidosis, and eventual cell death. The rate of dissociation between carbon monoxide and cytochrome oxidase is slow, causing a relatively prolonged impairment of oxidative metabolism.

Central nervous system effects

The mechanism that is thought to have a significant influence on delayed effects involves formed blood cells and chemical mediators, which cause brain lipid peroxidation (degradation of unsaturated fatty acids). Carbon monoxide causes endothelial cell and platelet release of nitric oxide, and the formation of oxygen free radicals including peroxynitrite. In the brain this causes further mitochondrial dysfunction, capillary leakage, leukocyte sequestration, and apoptosis. The result of these effects is lipid peroxidation, which causes delayed reversible demyelination of white matter in the central nervous system known as Grinker myelinopathy, which can lead to edema and necrosis within the brain. This brain damage occurs mainly during the recovery period. This may result in cognitive defects, especially affecting memory and learning, and movement disorders. These disorders are typically related to damage to the cerebral white matter and basal ganglia. Hallmark pathological changes following poisoning are bilateral necrosis of the white matter, globus pallidus, cerebellum, hippocampus and the cerebral cortex.

Pregnancy

Carbon monoxide poisoning in pregnant women may cause severe adverse fetal effects. Poisoning causes fetal tissue hypoxia by decreasing the release of maternal oxygen to the fetus. Carbon monoxide also crosses the placenta and combines with fetal hemoglobin, causing more direct fetal tissue hypoxia. Additionally, fetal hemoglobin has a 10 to 15% higher affinity for carbon monoxide than adult hemoglobin, causing more severe poisoning in the fetus than in the adult. Elimination of carbon monoxide is slower in the fetus, leading to an accumulation of the toxic chemical. The level of fetal morbidity and mortality in acute carbon monoxide poisoning is significant, so despite mild maternal poisoning or following maternal recovery, severe fetal poisoning or death may still occur.

History

Humans have maintained a complex relationship with carbon monoxide since first learning to control fire circa 800,000 BC. Primitive cavemen probably discovered the toxicity of carbon monoxide upon introducing fire into their dwellings. The early development of metallurgy and smelting technologies emerging circa 6,000 BC through the Bronze Age likewise plagued humankind with carbon monoxide exposure. Apart from the toxicity of carbon monoxide, indigenous Native Americans may have experienced the neuroactive properties of carbon monoxide through shamanistic fireside rituals.

Early civilizations developed mythological tales to explain the origin of fire, such as Vulcan, Pkharmat, and Prometheus from Greek mythology who shared fire with humans. Aristotle (384–322 BC) first recorded that burning coals produced toxic fumes. Greek physician Galen (129–199 AD) speculated that there was a change in the composition of the air that caused harm when inhaled, and symptoms of CO poisoning appeared in Cassius Iatrosophista's Quaestiones Medicae et Problemata Naturalia circa 130 AD. Julian the Apostate, Caelius Aurelianus, and several others similarly documented early knowledge of the toxicity symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning as caused by coal fumes in the ancient era.

Documented cases by Livy and Cicero allude to carbon monoxide being used as a method of suicide in ancient Rome. Emperor Lucius Verus used smoke to execute prisoners. Many deaths have been linked to carbon monoxide poisoning including Emperor Jovian, Empress Fausta, and Seneca. The most high-profile death by carbon monoxide poisoning may possibly have been Cleopatra or Edgar Allan Poe.

In the fifteenth century, coal miners believed sudden death was caused by evil spirits; carbon monoxide poisoning has been linked to supernatural and paranormal experiences, witchcraft, etc. throughout the following centuries including in the modern present day exemplified by Carrie Poppy's investigations.

Georg Ernst Stahl mentioned carbonarii halitus in 1697 in reference to toxic vapors thought to be carbon monoxide. Friedrich Hoffmann conducted the first modern scientific investigation into carbon monoxide poisoning from coal in 1716, notably rejecting villagers attributing death to demonic superstition. Herman Boerhaave conducted the first scientific experiments on the effect of carbon monoxide (coal fumes) on animals in the 1730s. Joseph Priestley is credited with first synthesizing carbon monoxide in 1772 which he had called heavy inflammable air, and Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated carbon monoxide from coal in 1773 suggesting it to be the toxic entity.

The dose-dependent risk of carbon monoxide poisoning as hydrocarbonate was investigated in the late 1790s by Thomas Beddoes, James Watt, Tiberius Cavallo, James Lind, Humphry Davy, and many others in the context of inhalation of factitious airs, much of which occurred at the Pneumatic Institution.

William Cruickshank discovered carbon monoxide as a molecule containing one carbon and one oxygen atom in 1800, thereby initiating the modern era of research exclusively focused on carbon monoxide. The mechanism for toxicity was first suggested by James Watt in 1793, followed by Adrien Chenot in 1854 and finally demonstrated by Claude Bernard after 1846 as published in 1857 and also independently published by Felix Hoppe-Seyler in the same year.

The first controlled clinical trial studying the toxicity of carbon monoxide occurred in 1973.

Historical detection

Carbon monoxide poisoning has plagued coal miners for many centuries. In the context of mining, carbon monoxide is widely known as whitedamp. John Scott Haldane identified carbon monoxide as the lethal constituent of afterdamp, the gas created by combustion, after examining many bodies of miners killed in pit explosions. By 1911, Haldane introduced the use of small animals for miners to detect dangerous levels of carbon monoxide underground, either white mice or canaries which have little tolerance for carbon monoxide thereby offering an early warning, i.e. canary in a coal mine. The canary in British pits was replaced in 1986 by the electronic gas detector.

The first qualitative analytical method to detect carboxyhemoglobin emerged in 1858 with a colorimetric method developed by Felix Hoppe-Seyler, and the first quantitative analysis method emerged in 1880 with Josef von Fodor.

Historical treatment

The use of oxygen emerged with anecdotal reports such as Humphry Davy having been treated with oxygen in 1799 upon inhaling three quarts of hydrocarbonate (water gas). Samuel Witter developed an oxygen inhalation protocol in response to carbon monoxide poisoning in 1814. Similarly, an oxygen inhalation protocol was recommend for malaria (literally translated to "bad air") in 1830 based on malaria symptoms aligning with carbon monoxide poisoning. Other oxygen protocols emerged in the late 1800s. The use of hyperbaric oxygen in rats following poisoning was studied by Haldane in 1895 while its use in humans began in the 1960s.

Incidents

See also the categories Deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning and Deaths by smoke inhalationSee also: Charcoal-burning suicideThe worst accidental mass poisoning from carbon monoxide was the Balvano train disaster which occurred on 3 March 1944 in Italy, when a freight train with many illegal passengers stalled in a tunnel, leading to the death of over 500 people.

Over 50 people are suspected to have died from smoke inhalation as a result of the Branch Davidian Massacre during the Waco siege in 1993.

Weaponization

Main article: Gas chamberIn ancient history, Hannibal executed Roman prisoners with coal fumes during the Second Punic War.

The extermination of stray dogs by a carbon monoxide gas chamber was described in 1874. In 1884, an article appeared in Scientific American describing the use of a carbon monoxide gas chamber for slaughterhouse operations as well as euthanizing a variety of animals.

As part of the Holocaust during World War II, the Nazis used gas vans at Chelmno extermination camp and elsewhere to murder an estimated 700,000 or more people by carbon monoxide poisoning. This method was also used in the gas chambers of several death camps such as Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec. Gassing with carbon monoxide started in Action T4. The gas was supplied by IG Farben in pressurized cylinders and fed by tubes into the gas chambers built at various mental hospitals, such as Hartheim Euthanasia Centre. Exhaust fumes from tank engines, for example, were used to supply the gas to the chambers.

References

- ^ National Center for Environmental Health (30 December 2015). "Carbon Monoxide Poisoning – Frequently Asked Questions". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Guzman JA (October 2012). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Critical Care Clinics. 28 (4): 537–48. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.007. PMID 22998990.

- ^ Schottke D (2016). Emergency Medical Responder: Your First Response in Emergency Care. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 224. ISBN 978-1284107272. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Caterino JM, Kahan S (2003). In a Page: Emergency medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 309. ISBN 978-1405103572. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Bleecker ML (2015). "Carbon monoxide intoxication". Occupational Neurology. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 131. pp. 191–203. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-62627-1.00024-X. ISBN 978-0444626271. PMID 26563790.

- ^ Hopper CP, De La Cruz LK, Lyles KV, Wareham LK, Gilbert JA, Eichenbaum Z, et al. (December 2020). "Role of Carbon Monoxide in Host-Gut Microbiome Communication". Chemical Reviews. 120 (24): 13273–13311. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00586. PMID 33089988. S2CID 224824871.

- Motterlini R, Foresti R (March 2017). "Biological signaling by carbon monoxide and carbon monoxide-releasing molecules". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 312 (3): C302–C313. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00360.2016. PMID 28077358.

- Yang X, de Caestecker M, Otterbein LE, Wang B (July 2020). "Carbon monoxide: An emerging therapy for acute kidney injury". Medicinal Research Reviews. 40 (4): 1147–1177. doi:10.1002/med.21650. PMC 7280078. PMID 31820474.

- ^ Hopper CP, Zambrana PN, Goebel U, Wollborn J (June 2021). "A brief history of carbon monoxide and its therapeutic origins". Nitric Oxide. 111–112: 45–63. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2021.04.001. PMID 33838343.

- ^ Penney DG (2007). Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. CRC Press. p. 569. ISBN 978-0849384189. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ Omaye ST (November 2002). "Metabolic modulation of carbon monoxide toxicity". Toxicology. 180 (2): 139–50. Bibcode:2002Toxgy.180..139O. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00387-6. PMID 12324190.

- Ferri FF (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 227–28. ISBN 978-0323448383. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- Blumenthal I (June 2001). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 94 (6): 270–2. doi:10.1177/014107680109400604. PMC 1281520. PMID 11387414.

- ^ Motterlini R, Otterbein LE (September 2010). "The therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 9 (9): 728–43. doi:10.1038/nrd3228. PMID 20811383. S2CID 205477130.

- "Carbon monoxide". ernet.in. Archived from the original on 2014-04-14.

- ^ Raub JA, Mathieu-Nolf M, Hampson NB, Thom SR (April 2000). "Carbon monoxide poisoning--a public health perspective". Toxicology. 145 (1): 1–14. Bibcode:2000Toxgy.145....1R. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(99)00217-6. PMID 10771127.

- "Carbon Monoxide". American Lung Association. Archived from the original on 2008-05-28. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Lipman GS (2006). "Carbon monoxide toxicity at high altitude". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 17 (2): 144–5. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2006)17[144:CMTAHA]2.0.CO;2. PMID 16805152.

- Raub J (1999). Environmental Health Criteria 213 (Carbon Monoxide). Geneva: International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization. ISBN 978-9241572132.

- ^ Campbell NK, Fitzgerald HK, Dunne A (January 2021). "Regulation of inflammation by the antioxidant haem oxygenase 1". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 21 (7): 411–425. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-00491-x. PMID 33514947. S2CID 231762031.

- ^ Goldfrank L, Flomenbaum N, Lewin N, Howland MA, Hoffman R, Nelson L (2002). "Carbon Monoxide". Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1689–1704. ISBN 978-0071360012.

- Foresti R, Bani-Hani MG, Motterlini R (April 2008). "Use of carbon monoxide as a therapeutic agent: promises and challenges". Intensive Care Medicine. 34 (4): 649–58. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1011-1. PMID 18286265. S2CID 6982787.

- ^ Prockop LD, Chichkova RI (November 2007). "Carbon monoxide intoxication: an updated review". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 262 (1–2): 122–30. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.037. PMID 17720201. S2CID 23892477.

- WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. World Health Organization. 2021. hdl:10665/345329. ISBN 978-92-4-003422-8.

- ^ Penney, David; Benignus, Vernon; Kephalopoulos, Stylianos; Kotzias, Dimitrios; Kleinman, Michael; Verrier, Agnes (2010). "Carbon monoxide". WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants. World Health Organization.

- Goldstein M (December 2008). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of Emergency Nursing. 34 (6): 538–42. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2007.11.014. PMID 19022078.

- Struttmann T, Scheerer A, Prince TS, Goldstein LA (Nov 1998). "Unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning from an unlikely source". The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 11 (6): 481–4. doi:10.3122/jabfm.11.6.481. PMID 9876005.

- ^ Kao LW, Nañagas KA (March 2006). "Toxicity associated with carbon monoxide". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 26 (1): 99–125. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2006.01.005. PMID 16567227.

- ^ Hardy KR, Thom SR (1994). "Pathophysiology and treatment of carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 32 (6): 613–29. doi:10.3109/15563659409017973. PMID 7966524.

- Hampson NB, Hampson LA (March 2002). "Characteristics of headache associated with acute carbon monoxide poisoning". Headache. 42 (3): 220–3. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02055.x. PMID 11903546. S2CID 8773611.

- ^ Choi IS (June 2001). "Carbon monoxide poisoning: systemic manifestations and complications". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 16 (3): 253–61. doi:10.3346/jkms.2001.16.3.253. PMC 3054741. PMID 11410684.

- Tritapepe L, Macchiarelli G, Rocco M, Scopinaro F, Schillaci O, Martuscelli E, Motta PM (April 1998). "Functional and ultrastructural evidence of myocardial stunning after acute carbon monoxide poisoning". Critical Care Medicine. 26 (4): 797–801. doi:10.1097/00003246-199804000-00034. PMID 9559621.

- ^ Weaver LK (March 2009). "Clinical practice. Carbon monoxide poisoning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (12): 1217–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0808891. PMID 19297574.

- ^ Carbon Monoxide Toxicity at eMedicine

- Marius-Nunez AL (February 1990). "Myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries after acute exposure to carbon monoxide". Chest. 97 (2): 491–4. doi:10.1378/chest.97.2.491. PMID 2298080.

- Gandini C, Castoldi AF, Candura SM, Locatelli C, Butera R, Priori S, Manzo L (2001). "Carbon monoxide cardiotoxicity". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 39 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1081/CLT-100102878. PMID 11327225. S2CID 46035819.

- Sokal JA (December 1985). "The effect of exposure duration on the blood level of glucose, pyruvate and lactate in acute carbon monoxide intoxication in man". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 5 (6): 395–7. doi:10.1002/jat.2550050611. PMID 4078220. S2CID 35144795.

- Henry CR, Satran D, Lindgren B, Adkinson C, Nicholson CI, Henry TD (January 2006). "Myocardial injury and long-term mortality following moderate to severe carbon monoxide poisoning". JAMA. 295 (4): 398–402. doi:10.1001/jama.295.4.398. PMID 16434630.

- Choi IS (July 1983). "Delayed neurologic sequelae in carbon monoxide intoxication". Archives of Neurology. 40 (7): 433–5. doi:10.1001/archneur.1983.04050070063016. PMID 6860181.

- Roohi F, Kula RW, Mehta N (July 2001). "Twenty-nine years after carbon monoxide intoxication". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 103 (2): 92–5. doi:10.1016/S0303-8467(01)00119-6. PMID 11516551. S2CID 1280793.

- Myers RA, Snyder SK, Emhoff TA (December 1985). "Subacute sequelae of carbon monoxide poisoning". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 14 (12): 1163–7. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(85)81022-2. PMID 4061987.

- ^ Fawcett TA, Moon RE, Fracica PJ, Mebane GY, Theil DR, Piantadosi CA (January 1992). "Warehouse workers' headache. Carbon monoxide poisoning from propane-fueled forklifts". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 34 (1): 12–5. PMID 1552375.

- ^ Johnson AC (2009). The Nordic Expert Group for criteria documentation of health risks from chemicals. 142, Occupational exposure to chemicals and hearing impairment. Morata, Thais C. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg. ISBN 978-9185971213. OCLC 939229378.

- Ryan CM (1990). "Memory disturbances following chronic, low-level carbon monoxide exposure". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 5 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1016/0887-6177(90)90007-C. PMID 14589544.

- Davutoglu V, Zengin S, Sari I, Yildirim C, Al B, Yuce M, Ercan S (November 2009). "Chronic carbon monoxide exposure is associated with the increases in carotid intima-media thickness and C-reactive protein level". The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 219 (3): 201–6. doi:10.1620/tjem.219.201. PMID 19851048.

- Shephard R (1983). Carbon Monoxide The Silent Killer. Springfield Illinois: Charles C Thomas. pp. 93–96.

- Allred EN, Bleecker ER, Chaitman BR, Dahms TE, Gottlieb SO, Hackney JD, et al. (November 1989). "Short-term effects of carbon monoxide exposure on the exercise performance of subjects with coronary artery disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (21): 1426–32. doi:10.1056/NEJM198911233212102. PMID 2682242.

- Fechter LD (2004). "Promotion of noise-induced hearing loss by chemical contaminants". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part A. 67 (8–10): 727–40. Bibcode:2004JTEHA..67..727F. doi:10.1080/15287390490428206. PMID 15192865. S2CID 5731842.

- ^ Bateman DN (October 2003). "Carbon Monoxide". Medicine. 31 (10): 233. doi:10.1383/medc.31.10.41.27810.

- Simini B (October 1998). "Cherry-red discolouration in carbon monoxide poisoning". Lancet. 352 (9134): 1154. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79807-X. PMID 9798630. S2CID 40041894.

- Brooks DE, Lin E, Ahktar J (February 2002). "What is cherry red, and who cares?". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 22 (2): 213–4. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(01)00469-3. PMID 11858933.

- ^ Varon J, Marik PE, Fromm RE, Gueler A (1999). "Carbon monoxide poisoning: a review for clinicians". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 17 (1): 87–93. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00128-0. PMID 9950394.

- Thom SR (October 2002). "Hyperbaric-oxygen therapy for acute carbon monoxide poisoning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (14): 1105–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMe020103. PMID 12362013.

- ^ Ernst A, Zibrak JD (November 1998). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (22): 1603–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811263392206. PMID 9828249.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (November 1996). "Deaths from motor-vehicle-related unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning--Colorado, 1996, New Mexico, 1980-1995, and United States, 1979-1992". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 45 (47): 1029–32. PMID 8965803. Archived from the original on 2017-06-24.

- Partrick M, Fiesseler F, Shih R, Riggs R, Hung O (2009). "Monthly variations in the diagnosis of carbon monoxide exposures in the emergency department". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 36 (3): 161–7. PMID 19860138.

- Heckerling PS (May 1987). "Occult carbon monoxide poisoning: a cause of winter headache". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 5 (3): 201–4. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(87)90320-2. PMID 3580051.

- "Department of Public Health Warns of Dangers of Carbon Monoxide Poisoning During Power Outages". Tower Generator. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- "Avoiding Carbon Monoxide poisoning during a power outage". CDC. Archived from the original on 2011-12-12. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- Klein KR, Herzog P, Smolinske S, White SR (2007). "Demand for poison control center services "surged" during the 2003 blackout". Clinical Toxicology. 45 (3): 248–54. doi:10.1080/15563650601031676. PMID 17453875. S2CID 29853571.

- Hampson NB (September 1998). "Emergency department visits for carbon monoxide poisoning in the Pacific Northwest". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16 (5): 695–8. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00080-8. PMID 9752939.

- "2004 Addendum to Overseas and Australian Statistics and Benchmarks for Customer Gas Safety Incidents" (PDF). Office of Gas Safety, Victoria. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24.

- "The risk of carbon monoxide poisoning from domestic gas appliances" (PDF). Report to the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism. Feb 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-12.

- ^ "Carbon Monoxide Detectors Can Save Lives: CPSC Document #5010". US Consumer Product Safety Commission. Archived from the original on 2009-04-09. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ^ Cobb N, Etzel RA (August 1991). "Unintentional carbon monoxide-related deaths in the United States, 1979 through 1988". JAMA. 266 (5): 659–63. doi:10.1001/jama.266.5.659. PMID 1712865.

- "Carbon Monoxide poisoning fact sheet" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- McDowell R, Fowles J, Phillips D (November 2005). "Deaths from poisoning in New Zealand: 2001-2002". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 118 (1225): U1725. PMID 16286939.

- Song KJ, Shin SD, Cone DC (September 2009). "Socioeconomic status and severity-based incidence of poisoning: a nationwide cohort study". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (8): 818–26. doi:10.1080/15563650903158870. PMID 19640232. S2CID 22203132.

- Salameh S, Amitai Y, Antopolsky M, Rott D, Stalnicowicz R (February 2009). "Carbon monoxide poisoning in Jerusalem: epidemiology and risk factors". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (2): 137–41. doi:10.1080/15563650801986711. PMID 18720104. S2CID 44624059.

- Liu Q, Zhou L, Zheng N, Zhuo L, Liu Y, Liu L (December 2009). "Poisoning deaths in China: type and prevalence detected at the Tongji Forensic Medical Center in Hubei". Forensic Science International. 193 (1–3): 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.09.013. PMID 19854011.

- Committee on Medical and Biological Effects of Environmental Pollutants (1977). Carbon Monoxide. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. p. 29. ISBN 978-0309026314.

- ^ Green W. "An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality: Carbon Monoxide (CO)". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- Singer SF. The Changing Global Environment. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 90.

- ^ Gosink T (1983-01-28). "What Do Carbon Monoxide Levels Mean?". Alaska Science Forum. Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Archived from the original on 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Roberts HC (September 1952), Report on the causes of, and circumstances attending, the explosion which occurred at Easington Colliery, County Durham, on the 29th May, 1951., Cmd 8646, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, p. 39, hdl:1842/5365

- "Man died from carbon monoxide poisoning after using 'heat beads' in Greystanes home". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2015-07-18. Archived from the original on 2015-07-19.

- Marc B, Bouchez-Buvry A, Wepierre JL, Boniol L, Vaquero P, Garnier M (June 2001). "Carbon-monoxide poisoning in young drug addicts due to indoor use of a gasoline-powered generator". Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 8 (2): 54–6. doi:10.1054/jcfm.2001.0474. PMID 16083675.

- Johnson CJ, Moran JC, Paine SC, Anderson HW, Breysse PA (October 1975). "Abatement of toxic levels of carbon monoxide in Seattle ice-skating rinks". American Journal of Public Health. 65 (10): 1087–90. doi:10.2105/AJPH.65.10.1087. PMC 1776025. PMID 1163706.

- "NIOSH Carbon Monoxide Hazards from Small Gasoline Powered Engines". United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Fife CE, Smith LA, Maus EA, McCarthy JJ, Koehler MZ, Hawkins T, Hampson NB (June 2009). "Dying to play video games: carbon monoxide poisoning from electrical generators used after hurricane Ike". Pediatrics. 123 (6): e1035-8. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3273. PMID 19482736. S2CID 6375808.

- Emmerich SJ (July 2011). Measured CO Concentrations at NIST IAQ Test House from Operation of Portable Electric Generators in Attached Garage – Interim Report (Report). United States National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- Hampson NB, Norkool DM (January 1992). "Carbon monoxide poisoning in children riding in the back of pickup trucks". JAMA. 267 (4): 538–40. doi:10.1001/jama.267.4.538. PMID 1370334.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (January 1996). "Carbon monoxide poisonings associated with snow-obstructed vehicle exhaust systems--Philadelphia and New York City, January 1996". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 45 (1): 1–3. PMID 8531914. Archived from the original on 2017-06-24.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (December 2000). "Houseboat-associated carbon monoxide poisonings on Lake Powell--Arizona and Utah, 2000". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 49 (49): 1105–8. PMID 11917924.

- "NIOSH Carbon Monoxide Dangers in Boating". United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Austin CC, Ecobichon DJ, Dussault G, Tirado C (December 1997). "Carbon monoxide and water vapor contamination of compressed breathing air for firefighters and divers". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 52 (5): 403–23. Bibcode:1997JTEHA..52..403A. doi:10.1080/00984109708984073. PMID 9388533.

- Dart RC (2004). Medical toxicology. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins. p. 1169. ISBN 978-0781728454.

- Trimdon Grange, Durham, 16 February 1882, archived from the original on 30 March 2017, retrieved 22 May 2012

- van Veen MP, Fortezza F, Spaans E, Mensinga TT (June 2002). "Non-professional paint stripping, model prediction and experimental validation of indoor dichloromethane levels". Indoor Air. 12 (2): 92–7. Bibcode:2002InAir..12...92V. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0668.2002.01109.x. PMID 12216472. S2CID 13941392.

- Kubic VL, Anders MW (March 1975). "Metabolism of dihalomethanes to carbon monoxide. II. In vitro studies". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 3 (2): 104–12. PMID 236156.

- Dueñas A, Felipe S, Ruiz-Mambrilla M, Martín-Escudero JC, García-Calvo C (January 2000). "CO poisoning caused by inhalation of CH3Cl contained in personal defense spray". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18 (1): 120–1. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(00)90070-6. PMID 10674554.

- US EPA, OCSPP (22 August 2019). "Final Rule on Regulation of Methylene Chloride in Paint and Coating Removal for Consumer Use". US EPA.

- Millar IL, Mouldey PG (June 2008). "Compressed breathing air - the potential for evil from within". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 38 (2): 145–51. PMID 22692708. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Krenzelok EP, Roth R, Full R (September 1996). "Carbon monoxide ... the silent killer with an audible solution". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 14 (5): 484–6. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90159-X. PMID 8765117.

- Lipinski ER (February 14, 1999). "Keeping Watch on Carbon Monoxide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- Yoon SS, Macdonald SC, Parrish RG (March 1998). "Deaths from unintentional carbon monoxide poisoning and potential for prevention with carbon monoxide detectors". JAMA. 279 (9): 685–7. doi:10.1001/jama.279.9.685. PMID 9496987.

- ^ NFPA 720: Standard for the Installation of Carbon Monoxide (CO) Detection and Warning Equipment. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Agency. 2009.

- "Gas Safety in the Home". UK Gas Safe Register. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- "MGL Ch. 148 §28F1/2 – Nicole's Law, effective March 31, 2006". malegislature.gov. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012.

- "Massachusetts Law About Carbon Monoxide Detectors". Trial Court Law Libraries. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2013-03-05. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- Bennetto L, Powter L, Scolding NJ (April 2008). "Accidental carbon monoxide poisoning presenting without a history of exposure: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2 (1): 118. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-118. PMC 2390579. PMID 18430228.

- Ford MD, Delaney KA, Ling LJ, Erickson T, eds. (2001). Clinical Toxicology. WB Saunders Company. p. 1046. ISBN 978-0721654850.

- Sato, Keizo; Tamaki, Keiji; Hattori, Hideki; Moore, Christine Mary; Tsutsumi, Hajime; Okajima, Hiroshi; Katsumata, Yoshinao (November 1990). "Determination of total hemoglobin in forensic blood samples with special reference to carboxyhemoglobin analysis". Forensic Science International. 48 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(90)90275-4. PMID 2279722.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 237–41.

- Keleş A, Demircan A, Kurtoğlu G (June 2008). "Carbon monoxide poisoning: how many patients do we miss?". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 15 (3): 154–7. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3282efd519. PMID 18460956. S2CID 20998393.

- Rodkey FL, Hill TA, Pitts LL, Robertson RF (August 1979). "Spectrophotometric measurement of carboxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin in blood". Clinical Chemistry. 25 (8): 1388–93. doi:10.1093/clinchem/25.8.1388. PMID 455674.

- Rees PJ, Chilvers C, Clark TJ (January 1980). "Evaluation of methods used to estimate inhaled dose of carbon monoxide". Thorax. 35 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1136/thx.35.1.47. PMC 471219. PMID 7361284.

- Coulange M, Barthelemy A, Hug F, Thierry AL, De Haro L (March 2008). "Reliability of new pulse CO-oximeter in victims of carbon monoxide poisoning". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 35 (2): 107–11. PMID 18500075.

- Maisel WH, Lewis RJ (October 2010). "Noninvasive measurement of carboxyhemoglobin: how accurate is accurate enough?". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 56 (4): 389–91. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.05.025. PMID 20646785.

- Vegfors M, Lennmarken C (May 1991). "Carboxyhaemoglobinaemia and pulse oximetry". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 66 (5): 625–6. doi:10.1093/bja/66.5.625. PMID 2031826.

- Barker SJ, Tremper KK (May 1987). "The effect of carbon monoxide inhalation on pulse oximetry and transcutaneous PO2". Anesthesiology. 66 (5): 677–9. doi:10.1097/00000542-198705000-00014. PMID 3578881.

- Jarvis MJ, Belcher M, Vesey C, Hutchison DC (November 1986). "Low cost carbon monoxide monitors in smoking assessment". Thorax. 41 (11): 886–7. doi:10.1136/thx.41.11.886. PMC 460516. PMID 3824275.

- Wald NJ, Idle M, Boreham J, Bailey A (May 1981). "Carbon monoxide in breath in relation to smoking and carboxyhaemoglobin levels". Thorax. 36 (5): 366–9. doi:10.1136/thx.36.5.366. PMC 471511. PMID 7314006.

- Ilano AL, Raffin TA (January 1990). "Management of carbon monoxide poisoning". Chest. 97 (1): 165–9. doi:10.1378/chest.97.1.165. PMID 2403894.

- Mathieu D (2006). Handbook on Hyperbaric Medicine (Online-Ausg. ed.). : Springer. ISBN 978-1402043765.

- ^ Olson KR (1984). "Carbon monoxide poisoning: mechanisms, presentation, and controversies in management". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 1 (3): 233–43. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(84)90078-7. PMID 6491241.

- Margulies JL (November 1986). "Acute carbon monoxide poisoning during pregnancy". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 4 (6): 516–9. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(86)80008-0. PMID 3778597.

- Brown DB, Mueller GL, Golich FC (November 1992). "Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for carbon monoxide poisoning in pregnancy: a case report". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 63 (11): 1011–4. PMID 1445151.

- ^ Buckley NA, Isbister GK, Stokes B, Juurlink DN (2005). "Hyperbaric oxygen for carbon monoxide poisoning : a systematic review and critical analysis of the evidence". Toxicological Reviews. 24 (2): 75–92. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524020-00002. hdl:1959.13/936317. PMID 16180928. S2CID 30011914.

- ^ Buckley NA, Juurlink DN, Isbister G, Bennett MH, Lavonas EJ (April 2011). "Hyperbaric oxygen for carbon monoxide poisoning". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (4): CD002041. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002041.pub3. PMC 7066484. PMID 21491385.

- Henry JA (2005). "Hyperbaric therapy for carbon monoxide poisoning : to treat or not to treat, that is the question". Toxicological Reviews. 24 (3): 149–50, discussion 159–60. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00002. PMID 16390211. S2CID 70992548.

- Olson KR (2005). "Hyperbaric oxygen or normobaric oxygen?". Toxicological Reviews. 24 (3): 151, discussion 159–60. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00003. PMID 16390212. S2CID 41578807.

- Seger D (2005). "The myth". Toxicological Reviews. 24 (3): 155–6, discussion 159–60. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00005. PMID 16390214. S2CID 40639134.

- Thom SR (2005). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for carbon monoxide poisoning : is it time to end the debates?". Toxicological Reviews. 24 (3): 157–8, discussion 159–60. doi:10.2165/00139709-200524030-00006. PMID 16390215. S2CID 71227659.

- Scheinkestel CD, Bailey M, Myles PS, Jones K, Cooper DJ, Millar IL, Tuxen DV (March 1999). "Hyperbaric or normobaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning: a randomised controlled clinical trial". The Medical Journal of Australia. 170 (5): 203–10. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb140318.x. PMID 10092916.

- Thom SR, Taber RL, Mendiguren II, Clark JM, Hardy KR, Fisher AB (April 1995). "Delayed neuropsychologic sequelae after carbon monoxide poisoning: prevention by treatment with hyperbaric oxygen". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 25 (4): 474–80. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70261-X. PMID 7710151.

- Raphael JC, Elkharrat D, Jars-Guincestre MC, Chastang C, Chasles V, Vercken JB, Gajdos P (August 1989). "Trial of normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide intoxication". Lancet. 2 (8660): 414–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90592-8. PMID 2569600. S2CID 26710636.

- Ducassé JL, Celsis P, Marc-Vergnes JP (March 1995). "Non-comatose patients with acute carbon monoxide poisoning: hyperbaric or normobaric oxygenation?". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 22 (1): 9–15. PMID 7742714. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Mathieu D, Mathieu-Nolf M, Durak C, Wattel F, Tempe JP, Bouachour G, Sainty JM (1996). "Randomized prospective study comparing the effect of HBO vs 12 hours NBO in non-comatose CO-poisoned patients: results of the preliminary analysis". Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine. 23: 7. Archived from the original on 2011-07-02. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Weaver LK, Hopkins RO, Chan KJ, Churchill S, Elliott CG, Clemmer TP, et al. (October 2002). "Hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (14): 1057–67. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013121. PMID 12362006.

- Gorman DF (June 1999). "Hyperbaric or normobaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Unfortunate methodological flaws". The Medical Journal of Australia. 170 (11): 563, author reply 564–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb127887.x. PMID 10397050. S2CID 28464628.

- Scheinkestel CD, Jones K, Myles PS, Cooper DJ, Millar IL, Tuxen DV (April 2004). "Where to now with carbon monoxide poisoning?". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 16 (2): 151–4. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2004.00567.x. PMID 15239731.

- Isbister GK, McGettigan P, Harris I (February 2003). "Hyperbaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (6): 557–60, author reply 557–60. doi:10.1056/NEJM200302063480615. PMID 12572577.

- Buckley NA, Juurlink DN (June 2013). "Carbon monoxide treatment guidelines must acknowledge the limitations of the existing evidence". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 187 (12): 1390. doi:10.1164/rccm.201212-2262LE. PMID 23767905.

- Tomaszewski C (January 1999). "Carbon monoxide poisoning. Early awareness and intervention can save lives". Postgraduate Medicine. 105 (1): 39–40, 43–8, 50. doi:10.3810/pgm.1999.01.496. PMID 9924492.

- Peirce EC (1986). "Treating acidemia in carbon monoxide poisoning may be dangerous". Journal of Hyperbaric Medicine. 1 (2): 87–97. Archived from the original on 2011-07-03. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Devine SA, Kirkley SM, Palumbo CL, White RF (October 2002). "MRI and neuropsychological correlates of carbon monoxide exposure: a case report". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (10): 1051–5. doi:10.1289/ehp.021101051. PMC 1241033. PMID 12361932.

- O'Donnell P, Buxton PJ, Pitkin A, Jarvis LJ (April 2000). "The magnetic resonance imaging appearances of the brain in acute carbon monoxide poisoning". Clinical Radiology. 55 (4): 273–80. doi:10.1053/crad.1999.0369. PMID 10767186.

- Seger D, Welch L (August 1994). "Carbon monoxide controversies: neuropsychologic testing, mechanism of toxicity, and hyperbaric oxygen". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 24 (2): 242–8. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70136-9. PMID 8037390.

- Chiang CL, Tseng MC (27 September 2011). "Safe use of electroconvulsive therapy in a highly suicidal survivor of carbon monoxide poisoning". General Hospital Psychiatry. 34 (1): 103.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.08.017. PMID 21958445.

- "Press Announcements - FDA allows marketing of new device to help treat carbon monoxide poisoning". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Gorman D, Drewry A, Huang YL, Sames C (May 2003). "The clinical toxicology of carbon monoxide". Toxicology. 187 (1): 25–38. Bibcode:2003Toxgy.187...25G. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00005-2. PMID 12679050.

- Townsend CL, Maynard RL (October 2002). "Effects on health of prolonged exposure to low concentrations of carbon monoxide". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 59 (10): 708–11. doi:10.1136/oem.59.10.708. PMC 1740215. PMID 12356933.

- Haldane J (November 1895). "The Action of Carbonic Oxide on Man". The Journal of Physiology. 18 (5–6): 430–62. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1895.sp000578. PMC 1514663. PMID 16992272.

- Stryer L, Berg J, Tymoczko J, Gatto G (2019-03-12). Biochemistry. Macmillan Learning. ISBN 978-1-319-11467-1.

- Gorman DF, Runciman WB (November 1991). "Carbon monoxide poisoning". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 19 (4): 506–11. doi:10.1177/0310057X9101900403. PMID 1750629.

- Alonso JR, Cardellach F, López S, Casademont J, Miró O (September 2003). "Carbon monoxide specifically inhibits cytochrome c oxidase of human mitochondrial respiratory chain". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 93 (3): 142–6. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.930306.x. PMID 12969439.

- ^ Blumenthal I (June 2001). "Carbon monoxide poisoning" (Free full text). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 94 (6): 270–2. doi:10.1177/014107680109400604. PMC 1281520. PMID 11387414.

- Fan HC, Wang AC, Lo CP, Chang KP, Chen SJ (July 2009). "Damage of cerebellar white matter due to carbon monoxide poisoning: a case report". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 27 (6): 757.e5–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.10.021. PMID 19751650.

- Fukuhara M, Abe I, Matsumura K, Kaseda S, Yamashita Y, Shida K, et al. (April 1996). "Circadian variations of blood pressure in patients with sequelae of carbon monoxide poisoning". American Journal of Hypertension. 9 (4 Pt 1): 300–5. doi:10.1016/0895-7061(95)00342-8. PMID 8722431.

- Greingor JL, Tosi JM, Ruhlmann S, Aussedat M (September 2001). "Acute carbon monoxide intoxication during pregnancy. One case report and review of the literature". Emergency Medicine Journal. 18 (5): 399–401. doi:10.1136/emj.18.5.399. PMC 1725677. PMID 11559621.

- Farrow JR, Davis GJ, Roy TM, McCloud LC, Nichols GR (November 1990). "Fetal death due to nonlethal maternal carbon monoxide poisoning". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 35 (6): 1448–52. doi:10.1520/JFS12982J. PMID 2262778.

- ^ Penney DG (2007). Carbon Monoxide Poisoning. CRC Press. p. 754. ISBN 978-0849384189. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Geiling N. "The (Still) Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- A scientific approach to the paranormal | Carrie Poppy. 27 March 2017. Event occurs at 4:01. Retrieved 2021-05-27 – via YouTube.

- Haine EA (1993). Railroad Wrecks. Associated University Presses. pp. 169–170. ISBN 0-8453-4844-2.

- "10 Things You May Not Know About Waco". FRONTLINE. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- "Killing food animals without pain". Scientific American. 51. Munn & Company: 148. 6 September 1884.

- Totten S, Bartrop P, Markusen E (2007). Dictionary of Genocide. Greenwood. pp. 129, 156. ISBN 978-0313346422. Archived from the original on 2013-05-26.

External links

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Carbon Monoxide – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (1999). Carbon Monoxide, Environmental Health Criteria 213, Geneva: WHO

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Inorganic |

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic |

| ||||||||||||

| Pharmaceutical |

| ||||||||||||

| Biological |

| ||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||