| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (June 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Melanocytic nevus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lentiginous melanocytic naevus | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

A melanocytic nevus (also known as nevocytic nevus, nevus-cell nevus, and commonly as a mole) is usually a noncancerous condition of pigment-producing skin cells. It is a type of melanocytic tumor that contains nevus cells. A mole can be either subdermal (under the skin) or a pigmented growth on the skin, formed mostly of a type of cell known as a melanocyte. The high concentration of the body's pigmenting agent, melanin, is responsible for their dark color. Moles are a member of the family of skin lesions known as nevi (singular "nevus"), occurring commonly in humans. Some sources equate the term "mole" with "melanocytic nevus", but there are also sources that equate the term "mole" with any nevus form.

The majority of moles appear during the first 2 decades of a person's life, with about 1 in every 100 babies being born with moles. Acquired moles are a form of benign neoplasm, while congenital moles, or congenital nevi, are considered a minor malformation or hamartoma and may be at a higher risk for melanoma.

Signs and symptoms

According to the American Academy of Dermatology, the most common types of moles are skin tags, raised moles, and flat moles. Benign moles are usually brown, tan, pink, or black (the latter especially on dark-colored skin). They are circular or oval and are usually small (commonly between 1–3 mm), though some can be larger than the size of a typical pencil eraser (>5 mm). Some moles produce dark, coarse hair. Common mole hair removal procedures include plucking, cosmetic waxing, electrolysis, threading, and cauterization.

Aging

Moles tend to appear during early childhood and during the first 30 years of life. They may change slowly, becoming raised, changing color, or gradually fading. Most people have between 30 and 40 moles, but some have as many as 600.

The number of moles a person has was found to have a correlation with telomere length. However, the relation between telomeres and aging remains uncertain.

Complications

The American Academy of Dermatology says that the vast majority of moles are benign. Data on the chances of transformation from melanocytic nevus to melanoma is controversial, but it appears that about 10% of malignant melanomas have a precursor lesion, of which about 10% are melanocytic nevi. Therefore, it appears that malignant melanoma quite seldom (1% of cases) has a melanocytic nevus as a precursor.

Cause

The cause of this condition is not clearly understood, but it is thought to result from a defect in embryologic development during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. The defect is thought to cause a proliferation of melanocytes, the cells responsible for normal skin color. When melanocytes are produced at an extremely rapid rate, they form in clusters instead of spreading out evenly, resulting in abnormal skin pigmentation in some areas of the body.

Genetics

Genes can influence a person's moles.

Dysplastic nevus syndrome is a largely hereditary condition that causes a person to have a large quantity of moles (often 100 or more), with some larger than normal or atypical. This often leads to a higher risk of melanoma, a serious type of skin cancer. Dysplastic nevi are more likely than ordinary moles to become cancerous. While dysplastic nevi are common and many people have a few of these abnormal moles, having more than 50 ordinary moles also increases the risk of developing melanoma.

In the general population, a slight majority of melanomas do not form in existing moles but rather create new growths on the skin. Somewhat surprisingly, this pattern also applies to those with dysplastic nevi. These individuals are at a higher risk of melanoma occurring not only where there is an existing mole but also in areas without moles. Consequently, such persons need regular examinations to check for changes in their moles and to identify any new ones.

Sunlight

Ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun causes premature aging of the skin and skin damage that can lead to melanoma. Researchers hypothesized that overexposure to UV, including excessive sunlight, may play a role in the formation of acquired moles. However, more research is needed to determine the complex interaction between genetic makeup and overall UV exposure. Some strong indications supporting this hypothesis (but falling short of proof) include:

- The relative lack of moles on the buttocks of people with dysplastic nevi

- The known influence of sunlight on freckles (spots of melanin on the skin, distinct from moles)

Studies have found that sunburns and excessive sun exposure can increase risk factors for melanoma. This is in addition to the higher risk already faced by individuals with dysplastic nevi (the uncertainty is in regards to acquiring benign moles). To prevent and reduce the risk of melanoma caused by UV radiation, the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Cancer Institute recommend:

- Staying out of the sun between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. standard time (or whenever one's shadow is shorter than one's height)

- Wearing long sleeves and trousers

- Wearing hats with a wide brim

- Applying sunscreens

- Wearing sunglasses that have UV-deflecting lenses

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis can be made with the naked eye using the ABCD guideline or by using dermatoscopy. An online-screening test is also available to help screen out benign moles.

Classification

Melanocytic nevi can mainly be classified by depth, being congenital versus acquired, and/or specific dermatoscopy or histopathology patterns:

- Depth

| Depth class | Location of nevus cells | Other characteristics | Image | ICD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Junctional nevus | Along the junction of the epidermis and the underlying dermis. | May be colored and slightly raised. |

|

ICD10: D22 ICDO: M8740/0 |

| Compound nevus | Both the epidermis and dermis. |

|

ICD10: D22 (ILDS D22.L14) ICDO: 8760/0 | |

| Intradermal nevus | Within the dermis. | A classic mole or birthmark. It typically appears as an elevated, dome-shaped bump on the surface of the skin. |

|

- Congenital versus acquired

- Congenital nevus: Small to large nevus present at or near time of birth. Small ones have low potential for forming melanomas, however the risk increases with size, as in the giant pigmented nevus.

- Acquired nevus: Any melanocytic nevus that is not a congenital nevus or not present at birth or near birth.

Specific dermatoscopy or histopathology patterns

| Type | Characteristics | Photo- graphy |

Histo- pathology |

|---|---|---|---|

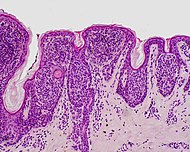

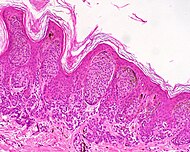

| Dysplastic nevus | Usually a compound nevus with cellular and architectural dysplasia. Like typical moles, dysplastic nevi can be flat or raised. While they vary in size, dysplastic nevi are typically larger than normal moles and tend to have irregular borders and irregular coloration. Hence, they resemble melanoma, appear worrisome, and are often removed to clarify the diagnosis. Dysplastic nevi are markers of risk when they are numerous, such as in people with dysplastic nevus syndrome. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), doctors believe that, when part of a series or syndrome of multiple moles, dysplastic nevi are more likely than ordinary moles to develop into the most virulent type of skin cancer called melanoma. |  In this case, the central portion is a complex papule, and the periphery is macular, irregular, indistinct and slightly pink. |

Characteristic rete ridge bridging, shouldering, and lamellar fibrosis. H&E stain. Characteristic rete ridge bridging, shouldering, and lamellar fibrosis. H&E stain.

|

| Blue nevus | It is blue in color as its melanocytes are very deep in the skin. |

|

|

| Spitz nevus | A distinct variant of intradermal nevus, usually in a child. |  They are raised and reddish (non-pigmented). They are raised and reddish (non-pigmented).

|

|

| Giant pigmented nevus | Large, pigmented, often hairy congenital nevi. They are important because melanoma may occasionally (10 to 15%) appear in them. |

|

|

| Nevus of Ito and nevus of Ota | Congenital, flat brownish lesions on the face or shoulder. |  |

|

| Mongolian spot | Congenital large, deep, bluish discoloration which generally disappears by puberty. It is named for its association with East Asian ethnic groups but is not limited to them. |

|

- Recurrence

Recurrent nevus: Any incompletely removed nevus with residual melanocytes left in the surgical wound. It creates a dilemma for the patient and physician, as these scars cannot be distinguished from a melanoma.

Differentiation from melanoma

It often requires a dermatologist to fully evaluate moles. For instance, a small blue or bluish-black spot, often called a blue nevus, is usually benign but often mistaken for melanoma. Conversely, a junctional nevus, which develops at the junction of the dermis and epidermis, is potentially cancerous.

A basic reference chart used for consumers to spot suspicious moles is found in the mnemonic A-B-C-D, used by institutions such as the American Academy of Dermatology and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The letters stand for asymmetry, border, color, and diameter. Sometimes, the letter E (for elevation or evolving) is added. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, if a mole starts changing in size, color, shape or, especially, if the border of a mole develops ragged edges or becomes larger than a pencil eraser, it would be an appropriate time to consult with a physician. Other warning signs include a mole, even if smaller than a pencil eraser, that is different from the others and begins to crust over, bleed, itch, or become inflamed. The changes may indicate developing melanomas. The matter can become clinically complicated because mole removal depends on which types of cancer, if any, come into suspicion.

A recent and novel method of melanoma detection is the "ugly duckling sign" It is simple, easy to teach, and highly effective in detecting melanoma. Simply, correlation of common characteristics of a person's skin lesion is made. Lesions which greatly deviate from the common characteristics are labeled as an "ugly duckling", and further professional exam is required. The "little red riding hood sign", suggests that individuals with fair skin and light colored hair might have difficult-to-diagnose melanomas. Extra care and caution should be rendered when examining such individuals as they might have multiple melanomas and severely dysplastic nevi. A dermatoscope must be used to detect "ugly ducklings", as many melanomas in these individuals resemble non-melanomas or are considered to be "wolves in sheep clothing". These fair skinned individuals often have lightly pigmented or amelanotic melanomas which will not present easy-to-observe color changes and variation in colors. The borders of these amelanotic melanomas are often indistinct, making visual identification without a dermatoscope very difficult.

People with a personal or family history of skin cancer or of dysplastic nevus syndrome (multiple atypical moles) should see a dermatologist at least once a year to be sure they are not developing melanoma.

Management

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

First, a diagnosis must be made. If the lesion is a seborrheic keratosis, then shave excision, electrodesiccation, or cryosurgery may be performed, usually leaving very little, if any scarring. If the lesion is suspected to be skin cancer, a skin biopsy must be done before considering removal. This is unless an excisional biopsy is warranted. If the lesion is a melanocytic nevus, one has to decide if it is medically indicated or not. Other reasons for removal may be cosmetic or because a raised mole interferes with daily life (e.g., shaving).

If a melanocytic nevus is suspected of being a melanoma, it needs to be sampled or removed via skin biopsy, and sent for microscopic evaluation by a pathologist. Depending on the size and location of the original nevus, a complete excisional skin biopsy or a punch skin biopsy can be done. Removal can also occur by shaving. Shaving leaves a red mark on the site but changes to the patient's usual skin color in about 2 weeks. However, there might still be a risk of spread of the melanoma, so the methods of melanoma diagnosis, including excisional biopsy, are still recommended even in these instances. Moles can also be removed by laser, surgery, or electrocautery.

In properly trained hands, some medical lasers are used to remove flat moles level with the surface of the skin, as well as some raised moles. While laser treatment is commonly offered and may require several appointments, other dermatologists think lasers are not the best method for removing moles because the laser only cauterizes or, in certain cases, removes very superficial levels of skin. Moles tend to go deeper into the skin than non-invasive lasers can penetrate. After a laser treatment, a scab is formed, which falls off about 7 days later, in contrast to surgery, where the wound has to be sutured. A second concern about the laser treatment is that if the lesion is a melanoma, and was misdiagnosed as a benign mole, the procedure might delay diagnosis. If the mole is incompletely removed by the laser, and the pigmented lesion regrows, it might form a recurrent nevus.

For surgery, many dermatologic and plastic surgeons first use a freezing solution, usually liquid nitrogen, on a raised mole and then shave it away with a scalpel. If the surgeon opts for the shaving method, he or she usually also cauterizes the stump. Because a circle is difficult to close with stitches, the incision is usually elliptical or eye-shaped. However, freezing should not be done to a nevus suspected to be a melanoma, as the ice crystals can cause pathological changes called "freezing artifacts" which might interfere with the diagnosis of the melanoma.

Electrocautery is available as an alternative to laser cautery. Electrocautery is a procedure that uses a light electrical current to burn moles, skin tags, and warts off the skin. Electric currents are set to a level such that they only reach the outermost layers of the skin, thus reducing the problem of scarring. Approximately 1–3 treatments may be needed to completely remove a mole. Typically, a local anesthetic is applied to the treated skin area before beginning the mole removal procedure.

Mole removal risks

The risks of mole removal mainly depend on the type of method used. First, mole removal may be followed by some discomfort that can be relieved with pain medication. Second, there is a risk that a scab will form or that redness will occur. However, such scabs and redness usually heal within 1 or 2 weeks. Third, similar to other surgeries, there is also risk of infection, allergic reactions to anesthesia, or even nerve damage. Lastly, the mole removal may leave an uncomfortable scar depending on the mole size.

Society and culture

Throughout human history, individuals who have possessed facial moles have been subject to ridicule and attack based on superstition. Throughout most of history, facial moles were not considered objects of beauty on lovely faces. Rather, most moles were considered hideous growths that appeared mostly on the noses, cheeks, and chins of witches, frogs, and other low creatures.

During the Salem witch trials, warts and other dermatological lesions such as moles, scars, and other blemishes, found on accused women were considered evidence of a pact with the devil.

Face mole reading

In traditional Chinese culture, facial moles are used in moleomancy, or face mole reading. Moles that can be easily seen may be considered warnings or reminders, while hidden moles may symbolize good luck and fortune. Furthermore, traditional Chinese culture holds that each facial mole indicates the presence of a corresponding mole on another part of the body. For instance, if a mole is present around the mouth, a corresponding mole should be found in the pubic region.

See also

References

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ^ Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1173. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ "Moles". Mayo Clinic. 18 February 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "What are moles?". American Academy of Dermatology. 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- "Moles, Freckles, Skin Tags: Types, Causes, Treatments". WebMD.

- "Skin moles link to delayed ageing". BBC News. 22 November 2010.

- Bataille V, Kato BS, Falchi M, et al. (July 2007). "Nevus size and number are associated with telomere length and represent potential markers of a decreased senescence in vivo". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 16 (7): 1499–1502. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0152. PMID 17627017.

- Gomes NM, Ryder OA, Houck ML, et al. (October 2011). "Comparative biology of mammalian telomeres: hypotheses on ancestral states and the roles of telomeres in longevity determination". Aging Cell. 10 (5): 761–768. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00718.x. PMC 3387546. PMID 21518243.

- Fernandes NC (2013). "The risk of cutaneous melanoma in melanocytic nevi". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 88 (2): 314–315. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962013000200030. PMC 3750908. PMID 23739702.

- Burkhart CG (2003). "Dysplastic nevus declassified: even the NIH recommends elimination of confusing terminology". Skinmed. 2 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2003.01724.x. PMID 14673319.

- ^ "What You Need To Know About Melanoma - Melanoma: Who's at Risk?". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- Pope DJ, Sorahan T, Marsden JR, Ball PM, Grimley RP, Peck IM (1992). "Benign pigmented nevi in children. Prevalence and associated factors: the West Midlands, United Kingdom Mole Study". Arch Dermatol. 128 (9): 1201–1206. doi:10.1001/archderm.128.9.1201. PMID 1519934.

- Goldgar DE, Cannon-Albright LA, Meyer LJ, Piepkorn MW, Zone JJ, Skolnick MH (1991). "Inheritance of nevus number and size in melanoma and dysplastic nevus syndrome kindreds". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 83 (23): 1726–1733. doi:10.1093/jnci/83.23.1726. PMID 1770551.

- van Schanke A, van Venrooij GM, Jongsma MJ, et al. (2006). "Induction of nevi and skin tumors in Ink4a/Arf Xpa knockout mice by neonatal, intermittent, or chronic UVB exposures". Cancer Res. 66 (5): 2608–2615. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2476. hdl:10029/7145. PMID 16510579.

- Junctional nevus entry in the public domain NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms

- "NCI Definition of Cancer Terms". www.cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "NCI Definition of Cancer Terms". www.cancer.gov. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "Giant congenital melanocytic nevus". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- "Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). NIH. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "Nevus of Ito". Genetic and Rare Disease Information Center (GARD). NIH. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "Mongolian Spot". AOCD Dermatologic Disease Database. American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Castagna, Rafaella Daboit; Stramari, Juliana Mazzoleni; Chemello, Raíssa Massaia Londero (July–August 2017). "The recurrent nevus phenomenon". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 92 (4): 531–533. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176190. PMC 5595602. PMID 28954104.

- Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, Mihm MC, Busam K (March 2001). "Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called 'malignant blue nevus'". Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 25 (3): 316–323. doi:10.1097/00000478-200103000-00005. PMID 11224601. S2CID 41306625.

- Hall J, Perry VE (1998). "Tinea nigra palmaris: differentiation from malignant melanoma or junctional nevi". Cutis. 62 (1): 45–46. PMID 9675534.

- "What You Need To Know About Melanoma - Signs and Symptoms". National Cancer Institute. January 1980. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- "The Ugly Duckling Sign: An Early Melanoma Recognition Tool". Archived from the original on 2009-01-30.

- ^ Mascaro JM, Mascaro JM (November 1998). "The dermatologist's position concerning nevi: a vision ranging from 'the ugly duckling' to 'little red riding hood'". Archives of Dermatology. 134 (11): 1484–1485. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1484. PMID 9828892. Archived from the original on 2014-07-15.

- "Dermoscopy. Introduction to dermoscopy. DermNet NZ". 3 March 2024.

- "Atypical Mole/Dyplastic Nevus - Skin Cancers - Medical Dermatology". DERMCARE. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Habif, Thomas P. (1985). Clinical dermatology, a color guide to diagnosis and therapy. Mosby. ISBN 0-8016-2233-6.

- "Mole Removal". Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- Flotte, T. J.; Bell, D. A. (1989-12-01). "Role of skin lesions in the Salem witchcraft trials". The American Journal of Dermatopathology. 11 (6): 582–587. doi:10.1097/00000372-198912000-00014. ISSN 0193-1091. PMID 2690652.

- "Chinese Face Reading - Facial Mole and Your Fate". Retrieved 2010-05-04.

External links

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Media related to Melanocytic nevus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Melanocytic nevus at Wikimedia Commons- Common Moles, Dysplastic Nevi, and Risk of Melanoma - National Cancer Institute.

| Skin cancer of nevi and melanomas | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | |||||||||||

| Nevus/ melanocytic nevus | |||||||||||