In poetry, a hendecasyllable (sometimes hendecasyllabic) is a line of eleven syllables. The term may refer to several different poetic meters, the older of which are quantitative and used chiefly in classical (Ancient Greek and Latin) poetry, and the newer of which are syllabic or accentual-syllabic and used in medieval and modern poetry.

Classical

In classical poetry, "hendecasyllable" or "hendecasyllabic" may refer to any of three distinct 11-syllable Aeolic meters, used first in Ancient Greece and later, with little modification, by Roman poets.

Aeolic meters are characterized by an Aeolic base × × followed by a choriamb – u u –; where – = a long syllable, u = a short syllable, and × = an anceps, that is, a syllable either long or short. The three Aeolic hendecasyllables (with base and choriamb in bold) are:

Phalaecian hendecasyllable

(Latin: hendecasyllabus phalaecius):

× × – u u – u – u – –

This line is named after Phalaecus, a minor poet probably of the 4th century BC, who used it in epigrams; though he did not invent it, since it had earlier been used by Sappho and Anacreon.

The Phalaecian hendecasyllable was a favorite of Catullus; it was also very frequently used by Martial. An example from Catullus is the first poem in his collection (with formal equivalent, substituting English stress for Latin length):

|

Cui dōnō lepidum novum libellum |

To whom dedicate this, my charming new book, |

| —Catullus: "Catullus 1", lines 1-4 |

The aeolic base (i.e., the first two syllables of the line) with – – is by far the most common in Catullus, and in later poets such as Statius and Martial was the only one used, but occasionally Catullus uses u – or – u as in lines 2 and 4 above. There is usually a caesura in the line after the 5th or 6th syllable.

In the first part of his poetry collection, Catullus uses the Phalaecian hendecasyllable as given above in 41 poems. In addition, in two of his poems (55 and 58b) Catullus uses a variation of the metre, in which the 4th and 5th syllables can sometimes be contracted into a single long syllable. In poem 55 there are twelve decasyllables and ten normal lines:

|

Ōrāmus, sī forte non molestum (e)st, |

We beg, if perhaps it is not a nuisance, |

| —Catullus: "Catullus 55", lines 1-2 |

Poem 58b is thought by some scholars to be a fragment which was formerly part of this one; although others think it an independent poem.

Alcaic hendecasyllable

Further information: Odes (Horace)(Latin: hendecasyllabus alcaicus):

× – u – × – u u – u –

Here the Aeolic base is truncated to a single anceps. This meter typically appears as the first two lines of an Alcaic stanza. (For an English example, see §English, below.)

Sapphic hendecasyllable

(Latin: hendecasyllabus sapphicus):

– u – × – u u – u – –

Again, the Aeolic base is truncated. This meter typically appears as the first three lines of a Sapphic stanza, though it was also sometimes used in stichic verse, for example by Seneca and Boethius. Sappho wrote many of the stanzas subsequently named after her, for example (with formal equivalent, substituting English stress for Greek length):

|

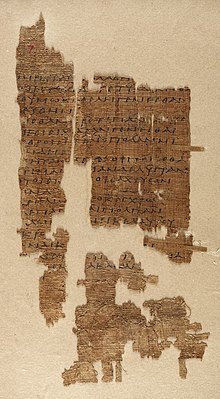

φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν |

He, it seems to me, is completely godlike: |

| —Sappho: Fragment 31, lines 1-4 |

Italian

The hendecasyllable (Italian: endecasillabo) is the principal metre in Italian poetry. Its defining feature is a constant stress on the tenth syllable, so that the number of syllables in the verse may vary, equaling eleven in the usual case where the final word is stressed on the penultimate syllable. The verse also has a stress preceding the caesura, on either the fourth or sixth syllable. The first case is called endecasillabo a minore, or lesser hendecasyllable, and has the first hemistich equivalent to a quinario; the second is called endecasillabo a maiore, or greater hendecasyllable, and has a settenario as the first hemistich.

There is a strong tendency for hendecasyllabic lines to end with feminine rhymes (causing the total number of syllables to be eleven, hence the name), but ten-syllable lines ("Ciò che 'n grembo a Benaco star non può") and twelve-syllable lines ("Ergasto mio, perché solingo e tacito") are encountered as well. Lines of ten or twelve syllables are more common in rhymed verse; versi sciolti, which rely more heavily on a pleasant rhythm for effect, tend toward a stricter eleven-syllable format. As a novelty, lines longer than twelve syllables can be created by the use of certain verb forms and affixed enclitic pronouns ("Ottima è l'acqua; ma le piante abbeverinosene.").

Additional accents beyond the two mandatory ones provide rhythmic variation and allow the poet to express thematic effects. A line in which accents fall consistently on even-numbered syllables ("Al còr gentìl rempàira sèmpre amóre") is called iambic (giambico) and may be a greater or lesser hendecasyllable. This line is the simplest, commonest and most musical but may become repetitive, especially in longer works. Lesser hendecasyllables often have an accent on the seventh syllable ("fàtta di giòco in figùra d'amóre"). Such a line is called dactylic (dattilico) and its less pronounced rhythm is considered particularly appropriate for representing dialogue. Another kind of greater hendecasyllable has an accent on the third syllable ("Se Mercé fosse amìca a' miei disìri") and is known as anapestic (anapestico). This sort of line has a crescendo effect and gives the poem a sense of speed and fluidity.

It is considered improper for the lesser hendecasyllable to use a word accented on its antepenultimate syllable (parola sdrucciola) for its mid-line stress. A line like "Più non sfavìllano quegli òcchi néri", which delays the caesura until after the sixth syllable, is not considered a valid hendecasyllable.

Most classical Italian poems are composed in hendecasyllables, including the major works of Dante, Francesco Petrarca, Ludovico Ariosto, and Torquato Tasso. The rhyme systems used include terza rima, ottava, sonnet and canzone, and some verse forms use a mixture of hendecasyllables and shorter lines. From the early 16th century onward, hendecasyllables are often used without a strict system, with few or no rhymes, both in poetry and in drama. This is known as verso sciolto. An early example is Le Api ("the bees") by Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai, written around 1517 and published in 1525 (with formal equivalent paraphrase which mirrors the original's syllabic counts, varied caesurae, and line- and hemistich-final stress profiles):

|

Mentr'era per cantare i vostri doni |

While your delightful gifts | I aimed at singing |

| —Rucellai: Le Api, lines 1-11 | —adapted from Leigh Hunt's blank verse translation |

Like other early Italian-language tragedies, the Sophonisba of Gian Giorgio Trissino (1515) is in blank hendecasyllables. Later examples can be found in the Canti of Giacomo Leopardi, where hendecasyllables are alternated with settenari.

Polish

The hendecasyllabic metre (Polish: jedenastozgłoskowiec) was very popular in Polish poetry, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, owing to strong Italian literary influence. It was used by Jan Kochanowski, Piotr Kochanowski (who translated Jerusalem Delivered by Torquato Tasso), Sebastian Grabowiecki, Wespazjan Kochowski and Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski. The greatest Polish Romantic poet, Adam Mickiewicz, set his poem Grażyna in this measure. The Polish hendecasyllable is widely used when translating English blank verse.

The eleven-syllable line is normally a line of 5+6 syllables with medial caesura, primary stresses on the fourth and tenth syllables, and feminine endings on both half-lines. Although the form can accommodate a fully iambic line, there is no such tendency in practice, word stresses falling variously on any of the initial syllables of each half-line.

o o o S s | o o o o S s o=any syllable, S=stressed syllable, s=unstressed syllable

A popular form of Polish literature that employs the hendecasyllable is the Sapphic stanza: 11/11/11/5.

The Polish hendecasyllable is often combined with an 8-syllable line: 11a/8b/11a/8b. Such a stanza was used by Mickiewicz in his ballads, as in the following example (with formal equivalent paraphrase):

|

Ktokolwiek będziesz w Nowogródzkiej stronie, |

Visitor passing Novogrudok's courses |

| —Adam Mickiewicz: "Świteź", lines 1-4 |

Portuguese

The hendecasyllable (Portuguese: hendecassílabo) is a common meter in Portuguese poetry. The best-known Portuguese poem composed in hendecasyllables is Luís de Camões' Lusiads, which begins as follows:

|

As armas, & os barões assinalados, |

Armes, and the Men above the vulgar File, |

| —Camões: Os Lusíadas, Canto I, lines 1-8 | —trans. Sir Richard Fanshawe |

In Portuguese, the hendecasyllable meter is often called "decasyllable" (decassílabo), even when the work in question uses overwhelmingly feminine rhymes (as is the case with the Lusiads). This is due to Portuguese prosody considering verses to end at the last stressed syllable, thus the aforementioned verses are effectively decasyllabic according to Portuguese scansion.

Spanish

The hendecasyllable (Spanish: endecasílabo) is less pervasive in Spanish poetry than in Italian or Portuguese, but it is commonly used with Italianate verse forms like sonnets and ottava rima (as found, for example, in Alonso de Ercilla's epic La Araucana).

Spanish dramatists often use hendecasyllables in tandem with shorter lines like heptasyllables, as can be seen in Rosaura's opening speech from Calderón's La vida es sueño:

|

Hipogrifo violento, |

Wild hippogriff swift speeding, |

| —Calderón: La vida es sueño I.i.1-8 | —trans. Denis Florence Mac-Carthy |

English

The term "hendecasyllable" most often refers to an imitation of Greek or Latin metrical lines, notably by Alfred Tennyson, Swinburne, and Robert Frost ("For Once Then Something"). Contemporary American poets Annie Finch ("Lucid Waking") and Patricia Smith ("The Reemergence of the Noose") have published recent examples. In English, which lacks phonemic length, poets typically substitute stressed syllables for long, and unstressed syllables for short. Tennyson, however, attempted to maintain the quantitative features of the meter (while supporting them with concurrent stress) in his Alcaic stanzas, the first two lines of which are Alcaic hendecasyllables:

O mighty-mouth'd inventor of harmonies,

— Tennyson: "Milton", lines 1-4

O skill'd to sing of Time or Eternity,

God-gifted organ-voice of England,

Milton, a name to resound for ages;

Occasionally "hendecasyllable" is used to denote a line of iambic pentameter with a feminine ending, as in the first line of John Keats's Endymion: "A thing of beauty is a joy for ever".

See also

References

- Halporn, James W.; Ostwald, Martin; Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. (1980). The Meters of Greek and Latin Poetry (Revised ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 129–132. ISBN 0-87220-243-7.

- ^ Halporn, James W.; Ostwald, Martin; Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. (1980). The Meters of Greek and Latin Poetry (Revised ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 29–34, 97–102. ISBN 0-87220-243-7.

- William Smith (1873). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology: Phalaecus.

- Raven, D. S. (1965). Latin Metre, pp. 177, 180–181.

- Quinn, Kenneth, ed. (1973). Catullus: The Poems (2nd ed.). London: St. Martin's Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-333-01787-0.

- D. S. Raven (1965), Latin Metre (Faber), p. 139.

- Fordyce (1961). Catullus, p. 225.

- Fordyce (1961). Catullus, p. 226.

- "Phainetai Moi". www.stoa.org. n.d. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Claudio Ciociola (2010) "Endecasillabo", Enciclopedia dell'Italiano (in Italian). Accessed March 2013.

- Hunt, Leigh (October 1844). "A Jar of Honey from Mount Hybla [No. XI]". Ainsworth's Magazine. 6. Open Court Publishing Co: 390–395.

- Alamanni, Luigi; Rucellai, Giovanni (1804). Bianchini, Giuseppe Maria; Titi, Roberto (eds.). La Coltivazione di Luigi Alamanni e Le Api di Giovanni Rucellai. Milan: Società Tipografica de'Classici Italiani. pp. 239–240.

- Compare: Summary Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 398.

- ^ Gasparov, M. L. (1996). Smith, G. S.; Holford-Strevens, L. (eds.). A History of European Versification. Translated by Smith, G. S.; Tarlinskaja, Marina. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 220. ISBN 0-19-815879-3. OCLC 1027190450.

- Mickiewicz, Adam (1852). Ballady i romanse (in Polish). Lipsk: F. A. Brockhaus. p. 10.

- Camões, Luís de (1572). Os Lusiadas. Lisbon: Antonio Goçaluez impressor. p. 1.

- Camões, Luís de (1963). Bullough, Geoffrey (ed.). The Lusiads. Translated by Fanshawe, Sir Richard. London: Centaur Press. p. 59.

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro (1905). Gröber, Gustav (ed.). La vida es sueño. Strasbourg: J.H.E. Heitz. pp. 13–14.

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro (1873). Dramas. Translated by Mac-Carthy, Denis Florence. London: Henry S. King. p. 7.

- Tennyson, Alfred (1864). Enoch Arden, &c. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. p. 200.

Further reading

Italian texts

- Raffaele Spongano, Nozioni ed esempi di metrica italiana, Bologna, R. Pàtron, 1966

- Angelo Marchese, Dizionario di retorica e di stilistica, Milano, Mondadori, 1978

- Mario Pazzaglia, Manuale di metrica italiana, Firenze, Sansoni, 1990

Polish texts

- Wiktor Jarosław Darasz, Mały przewodnik po wierszu polskim, Kraków 2003.