The following is a list of second moments of area of some shapes. The second moment of area, also known as area moment of inertia, is a geometrical property of an area which reflects how its points are distributed with respect to an arbitrary axis. The unit of dimension of the second moment of area is length to fourth power, L, and should not be confused with the mass moment of inertia. If the piece is thin, however, the mass moment of inertia equals the area density times the area moment of inertia.

Second moments of area

Please note that for the second moment of area equations in the below table: and

| Description | Figure | Second moment of area | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| A filled circular area of radius r |

|

is the second polar moment of area. | |

| An annulus of inner radius r1 and outer radius r2 |

|

For thin tubes, and and so to first order in , . So, for a thin tube, and . is the second polar moment of area. | |

| A filled circular sector of angle θ in radians and radius r with respect to an axis through the centroid of the sector and the center of the circle |  |

This formula is valid only for 0 ≤ ≤ | |

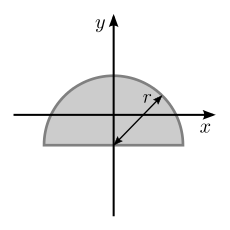

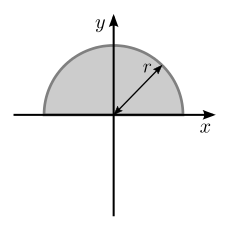

| A filled semicircle with radius r with respect to a horizontal line passing through the centroid of the area |

|

||

| A filled semicircle as above but with respect to an axis collinear with the base |

|

: This is a consequence of the parallel axis theorem and the fact that the distance between the x axes of the previous one and this one is | |

| A filled quarter circle with radius r with the axes passing through the bases |

|

||

| A filled quarter circle with radius r with the axes passing through the centroid |

|

This is a consequence of the parallel axis theorem and the fact that the distance between these two axes is | |

| A filled ellipse whose radius along the x-axis is a and whose radius along the y-axis is b |

|

||

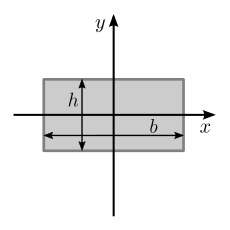

| A filled rectangular area with a base width of b and height h |

|

||

| A filled rectangular area as above but with respect to an axis collinear with the base |

|

This is a result from the parallel axis theorem | |

| A hollow rectangle with an inner rectangle whose width is b1 and whose height is h1 |

|

||

| A filled triangular area with a base width of b, height h and top vertex displacement a, with respect to an axis through the centroid |  |

||

| A filled triangular area as above but with respect to an axis collinear with the base |  |

This is a consequence of the parallel axis theorem | |

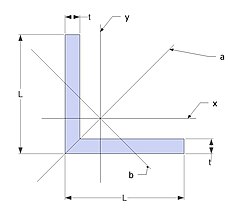

| An equal legged angle, commonly found in engineering applications |

|

is the often unused "product second moment of area", used to define principal axes |

| Regular polygons | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Figure | Second moment of area | Comment |

| A filled regular (equiliteral) triangle with a side length of a |

|

The result is valid for both a horizontal and a vertical axis through the centroid, and therefore is also valid for an axis with arbitrary direction that passes through the origin.

This holds true for all regular polygons. | |

| A filled square with a side length of a |

|

The result is valid for both a horizontal and a vertical axis through the centroid, and therefore is also valid for an axis with arbitrary direction that passes through the origin.

This holds true for all regular polygons. | |

| A filled regular hexagon with a side length of a |

|

The result is valid for both a horizontal and a vertical axis through the centroid, and therefore is also valid for an axis with arbitrary direction that passes through the origin.

This holds true for all regular polygons. | |

| A filled regular octagon with a side length of a |

|

The result is valid for both a horizontal and a vertical axis through the centroid, and therefore is also valid for an axis with arbitrary direction that passes through the origin.

This holds true for all regular polygons. | |

Parallel axis theorem

The parallel axis theorem can be used to determine the second moment of area of a rigid body about any axis, given the body's second moment of area about a parallel axis through the body's centroid, the area of the cross section, and the perpendicular distance (d) between the axes.

See also

References

- "Circle". eFunda. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "Circular Half". eFunda. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "Quarter Circle". eFunda. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "Rectangular area". eFunda. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "Triangular area". eFunda. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ Young, Warren C; Budynas, Richard G. "Appendix A: Properties of a Plane Area". Roark's Formulas for Stress and Strain. Seventh Edition (PDF). pp. 802–812. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

and

and

is the

is the

and

and  and so to first order in

and so to first order in  ,

,  . So, for a thin tube,

. So, for a thin tube,  and

and  .

.

≤

≤

: This is a consequence of the

: This is a consequence of the

is the often unused "product second moment of area", used to define principal axes

is the often unused "product second moment of area", used to define principal axes