| Manatees Temporal range: Early Pleistocene – Recent 2.5–0 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ | |

|---|---|

| |

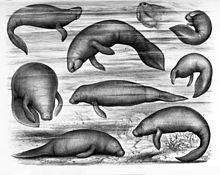

| Clockwise from upper left: West Indian manatee, Amazonian manatee, African manatee | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Sirenia |

| Family: | Trichechidae |

| Subfamily: | Trichechinae |

| Genus: | Trichechus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Trichechus manatus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Manatees (/ˈmænətiːz/, family Trichechidae, genus Trichechus) are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing three of the four living species in the order Sirenia: the Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis), the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus), and the West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis). They measure up to 4.0 metres (13 ft 1 in) long, weigh as much as 590 kilograms (1,300 lb), and have paddle-like tails.

Manatees are herbivores and eat over 60 different freshwater and saltwater plants. Manatees inhabit the shallow, marshy coastal areas and rivers of the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the Amazon basin, and West Africa.

The main causes of death for manatees are human-related issues, such as habitat destruction and human objects. Their slow-moving, curious nature has led to violent collisions with propeller-driven boats and ships. Some manatees have been found with over 50 scars on them from propeller blades. Natural causes of death include adverse temperatures, predation by crocodiles on young, and disease.

Etymology

The etymology of the name is unclear, with connections having been made to Latin manus "hand" and to Carib manaty "breast". The term sea cow is a reference to the species' slow, peaceful, herbivorous nature, reminiscent of that of bovines.

Taxonomy

Manatees are three of the four living species in the order Sirenia. The fourth is the Eastern Hemisphere's dugong. The Sirenia are thought to have evolved from four-legged land mammals more than 60 million years ago, with the closest living relatives being the Proboscidea (elephants) and Hyracoidea (hyraxes).

Description

Manatees weigh 400 to 550 kg (880 to 1,210 lb), and average 2.8 to 3.0 m (9 ft 2 in to 9 ft 10 in) in length, sometimes growing to 4.6 m (15 ft 1 in) and 1,775 kg (3,913 lb) and females tend to be larger and heavier than males. At birth, baby manatees weigh about 30 kg (66 lb) each. The female manatee has two teats, one under each flipper, a characteristic that was used to make early links between the manatee and elephants.

The lids of manatees' small, widely spaced eyes close in a circular manner. The manatee has a large, flexible, prehensile upper lip, used to gather food and eat and for social interaction and communication. Manatees have shorter snouts than their fellow sirenians, the dugongs.

Manatee adults have no incisor or canine teeth, just a set of cheek teeth, which are not clearly differentiated into molars and premolars. These teeth are repeatedly replaced throughout life, with new teeth growing at the rear as older teeth fall out from farther forward in the mouth, somewhat as elephants' teeth do. At any time, a manatee typically has no more than six teeth in each jaw of its mouth.

The manatee's tail is paddle-shaped, and is the clearest visible difference between manatees and dugongs; a dugong tail is fluked, similar in shape to that of a whale.

The manatee is unusual among mammals in having just six cervical vertebrae, a number that may be due to mutations in the homeotic genes. All other mammals have seven cervical vertebrae, other than the two-toed and three-toed sloths.

Like the horse, the manatee has a simple stomach, but a large cecum, in which it can digest tough plant matter. Generally, the intestines are about 45 meters, unusually long for an animal of the manatee's size.

Evolution

Fossil remains of manatee ancestors - also known as sirenians - date back to the Early Eocene. It is thought that they reached the isolated area of the South American continent and became known as Trichechidae. In the Late Miocene, trichechids were likely restricted in South American coastal rivers and they fed on many freshwater plants. Dugongs inhabited the West Atlantic and Caribbean waters and fed on seagrass meadows instead. As the sea grasses began to grow, manatees adapted to the changing environment by growing supernumerary molars. Sea levels lowered and increased erosion and silt runoff was caused by glaciation. This increased the tooth wear of the bottom-feeding manatees.

Behavior

Apart from mothers with their young, or males following a receptive female, manatees are generally solitary animals. Manatees spend approximately 50% of the day sleeping submerged, surfacing for air regularly at intervals of less than 20 minutes. The remainder of the time is mostly spent grazing in shallow waters at depths of 1–2 m (3 ft 3 in – 6 ft 7 in). The Florida subspecies (T. m. latirostris) has been known to live up to 60 years.

Locomotion

Generally, manatees swim at about 5 to 8 km/h (3 to 5 mph). However, they have been known to swim at up to 30 km/h (20 mph) in short bursts.

Intelligence and learning

Manatees are capable of understanding discrimination tasks and show signs of complex associative learning. They also have good long-term memory. They demonstrate discrimination and task-learning abilities similar to dolphins and pinnipeds in acoustic and visual studies. Social interactions between manatees are highly complex and intricate, which may indicate higher intelligence than previously thought, although they remain poorly understood by science.

Reproduction

Manatees typically breed once every two years; generally only a single calf is born. Gestation lasts about 12 months and to wean the calf takes a further 12 to 18 months, although females may have more than one estrous cycle per year.

Communication

Manatees emit a wide range of sounds used in communication, especially between cows and their calves. Their ears are large internally but the external openings are small, and they are located four inches behind each eye. Adults communicate to maintain contact and during sexual and play behaviors. Taste and smell, in addition to sight, sound, and touch, may also be forms of communication.

Diet

Manatees are herbivores and eat over 60 different freshwater (e.g., floating hyacinth, pickerel weed, alligator weed, water lettuce, hydrilla, water celery, musk grass, mangrove leaves) and saltwater plants (e.g., sea grasses, shoal grass, manatee grass, turtle grass, widgeon grass, sea clover, and marine algae). Using their divided upper lip, an adult manatee will commonly eat up to 10%–15% of their body weight (about 50 kg) per day. Consuming such an amount requires the manatee to graze for up to seven hours a day. To be able to cope with the high levels of cellulose in their plant based diet, manatees utilize hindgut fermentation to help with the digestion process. Manatees have been known to eat small numbers of fish from nets.

Feeding behavior

Manatees use their flippers to "walk" along the bottom whilst they dig for plants and roots in the substrate. When plants are detected, the flippers are used to scoop the vegetation toward the manatee's lips. The manatee has prehensile lips; the upper lip pad is split into left and right sides which can move independently. The lips use seven muscles to manipulate and tear at plants. Manatees use their lips and front flippers to move the plants into the mouth. The manatee does not have front teeth, however, behind the lips, on the roof of the mouth, there are dense, ridged pads. These horny ridges, and the manatee's lower jaw, tear through ingested plant material.

Dentition

Manatees have four rows of teeth. There are 6 to 8 high-crowned, open-rooted molars located along each side of the upper and lower jaw giving a total of 24 to 32 flat, rough-textured teeth. Eating gritty vegetation abrades the teeth, particularly the enamel crown; however, research indicates that the enamel structure in manatee molars is weak. To compensate for this, manatee teeth are continually replaced. When anterior molars wear down, they are shed. Posterior molars erupt at the back of the row and slowly move forward to replace these like enamel crowns on a conveyor belt, similarly to elephants. This process continues throughout the manatee's lifetime. The rate at which the teeth migrate forward depends on how quickly the anterior teeth abrade. Some studies indicate that the rate is about 1 cm/month although other studies indicate 0.1 cm/month.

Ecology

Range and habitat

Manatees inhabit the shallow, marshy coastal areas and rivers of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico (T. manatus, West Indian manatee), the Amazon basin (T. inunguis, Amazonian manatee), and West Africa (T. senegalensis, West African manatee).

West Indian manatees prefer warmer temperatures and are known to congregate in shallow waters. They frequently migrate through brackish water estuaries to freshwater springs. They cannot survive below 15 °C (60 °F). Their natural source for warmth during winter is warm, spring-fed rivers.

West Indian

The coast of the state of Georgia is usually the northernmost range of the West Indian manatees because their low metabolic rate does not protect them in cold water. Prolonged exposure to water below 20 °C (68 °F) can cause "cold stress syndrome" and death.

West Indian manatees can move freely between fresh water and salt water. However, studies suggest that they are susceptible to dehydration if freshwater is not available for an extended period of time.

Manatees can travel hundreds of miles annually, and have been seen as far north as Cape Cod, and in 1995 and again in 2006, one was seen in New York City and Rhode Island's Narragansett Bay. A manatee was spotted in the Wolf River harbor near the Mississippi River in downtown Memphis in 2006, and was later found dead 16 km (10 mi) downriver in McKellar Lake. Another manatee was found dead on a New Jersey beach in February 2020, considered especially unusual given the time of year. At the time of the manatee's discovery, the water temperature in the area was below 6.5 °C (43.7 °F).

The West Indian manatee migrates into Florida rivers—such as the Crystal, the Homosassa, and the Chassahowitzka rivers, whose headsprings are 22 °C (72 °F) all year. Between November and March each year, about 600 West Indian manatees gather in the rivers in Citrus County, Florida such as the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge.

In winter, manatees often gather near the warm-water outflows of power plants along the Florida coast, instead of migrating south as they once did. Some conservationists are concerned that these manatees have become too reliant on these artificially warmed areas.

Accurate population estimates of the West Indian manatee in Florida are difficult. They have been called scientifically weak because they vary widely from year to year, with most areas showing decreases, and little strong evidence of increases except in two areas. Manatee counts are highly variable without an accurate way to estimate numbers. In Florida in 1996, a winter survey found 2,639 manatees; in 1997, a January survey found 2,229, and a February survey found 1,706. A statewide synoptic survey in January 2010 found 5,067 manatees living in Florida, the highest number recorded to that time.

As of January 2016, the USFWS estimates the range-wide West Indian manatee population to be at least 13,000; as of January 2018, at least 6,100 are estimated to be in Florida.

Population viability studies conducted in 1997 found that decreasing adult survival and eventual extinction were probable future outcomes for Florida manatees unless they received more protection. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed downgrading the manatee's status from endangered to threatened in January 2016 after more than 40 years.

There is a small population of the subspecies Antillean manatee (T. m. manatus) found in Mexico's Caribbean coastal area. The best estimate for this population is 200-250. As of 2022, a new manatee habitat was discovered by Klaus Thymann within the cenotes of Sian Ka'an Biosphere Reserve on the Yucatán Peninsula. The explorer and his team documented the discovery with a 12-minute film that is available on the interactive streaming platform WaterBear. The discovery got picked up by the New Scientist in 2024, who featured in a 10-minute short film.

Amazonian

The freshwater Amazonian manatee (T. inunguis) inhabits the Central Amazon Basin in Brazil, eastern Perú, southeastern Colombia, but not Ecuador. It is the only exclusively freshwater manatee, and is also the smallest. Since they are unable to reduce peripheral heat loss, it is found primarily in tropical waters.

West African

They are found in coastal marine and estuarine habitats, and in freshwater river systems along the west coast of Africa from the Senegal River south to the Cuanza River in Angola. They live as far upriver on the Niger River as Koulikoro in Mali, 2,000 km (1,200 mi) from the coast.

Predation

In relation to the threat posed by humans, predation does not present a significant threat to manatees. When threatened, the manatee's response is to dive as deeply as it can, suggesting that threats have most frequently come from land dwellers such as humans rather than from other water-dwelling creatures such as caimans or sharks.

Relation to humans

Main article: Manatee conservationThreats

The main causes of death for manatees are human-related issues, such as habitat destruction and human objects. Natural causes of death include adverse temperatures, predation by crocodiles on young, and disease.

Ship strikes

Their slow-moving, curious nature, coupled with dense coastal development, has led to many violent collisions with propeller-driven boats and ships, leading frequently to maiming, disfigurement, and even death. As a result, a large proportion of manatees exhibit spiral cutting propeller scars on their backs, usually caused by larger vessels that do not have skegs in front of the propellers like the smaller outboard and inboard-outboard recreational boats have. They are now even identified by humans based on their scar patterns. Many manatees have been cut in two by large vessels like ships and tug boats, even in the highly populated lower St. Johns River's narrow channels. Some are concerned that the current situation is inhumane, with upwards of 50 scars and disfigurements from vessel strikes on a single manatee. Often, the lacerations lead to infections, which can prove fatal. Internal injuries stemming from being trapped between hulls and docks and impacts have also been fatal. Recent testing shows that manatees may be able to hear speed boats and other watercraft approaching, due to the frequency the boat makes. However, a manatee may not be able to hear the approaching boats when they are performing day-to-day activities or distractions. The manatee has a tested frequency range of 8 to 32 kilohertz.

Manatees hear on a higher frequency than would be expected for such large marine mammals. Many large boats emit very low frequencies, which confuse the manatee and explain their lack of awareness around boats. The Lloyd's mirror effect results in low frequency propeller sounds not being discernible near the surface, where most accidents occur. Research indicates that when a boat has a higher frequency the manatees rapidly swim away from danger.

In 2003, a population model was released by the United States Geological Survey that predicted an extremely grave situation confronting the manatee in both the Southwest and Atlantic regions where the vast majority of manatees are found. It states,

In the absence of any new management action, that is, if boat mortality rates continue to increase at the rates observed since 1992, the situation in the Atlantic and Southwest regions is dire, with no chance of meeting recovery criteria within 100 years. "Hurricanes, cold stress, red tide poisoning and a variety of other maladies threaten manatees, but by far their greatest danger is from watercraft strikes, which account for about a quarter of Florida manatee deaths," said study curator John Jett.

According to marine mammal veterinarians:

The severity of mutilations for some of these individuals can be astounding – including long term survivors with completely severed tails, major tail mutilations, and multiple disfiguring dorsal lacerations. These injuries not only cause gruesome wounds, but may also impact population processes by reducing calf production (and survival) in wounded females – observations also speak to the likely pain and suffering endured. In an example, they cited one case study of a small calf "with a severe dorsal mutilation trailing a decomposing piece of dermis and muscle as it continued to accompany and nurse from its mother ... by age 2 its dorsum was grossly deformed and included a large protruding rib fragment visible."

These veterinarians go on to state:

he overwhelming documentation of gruesome wounding of manatees leaves no room for denial. Minimization of this injury is explicit in the Recovery Plan, several state statutes, and federal laws, and implicit in our society's ethical and moral standards.

One quarter of annual manatee deaths in Florida are caused by boat collisions with manatees. In 2009, of the 429 Florida manatees recorded dead, 97 were killed by commercial and recreational vessels, which broke the earlier record number of 95 set in 2002.

Red tide

Another cause of manatee deaths are red tides, a term used for the proliferation, or "blooms", of the microscopic marine algae Karenia brevis. This dinoflagellate produces brevetoxins that can have toxic effects on the central nervous system of animals.

In 1996, a red tide was responsible for 151 manatee deaths in Florida. The bloom was present from early March to the end of April and killed approximately 15% of the known population of manatees along South Florida's western coast. Other blooms in 1982 and 2005 resulted in 37 and 44 deaths respectively, and a red tide killed 123 manatees between November 2022 and June 2023.

Starvation

In 2021 a massive die-off of seagrass along the Atlantic coast of Florida left manatees without enough food to eat. As a result of this ecological disaster Florida's manatees began dying at an alarming rate, largely from starvation. In early 2022 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began a feeding program to address the situation by distributing 3,000 pounds (1,361 kg) of lettuce per day to save the malnourished animals.

Additional threats

Manatees can also be crushed and isolated in water control structures (navigation locks, floodgates, etc.) and are occasionally killed by entanglement in fishing gear, such as crab pot float lines, box traps, and shark nets.

While humans are allowed to swim with manatees in one area of Florida, there have been numerous charges of people harassing and disturbing the manatees. According to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, approximately 99 manatee deaths each year are related to human activities. In January 2016, there were 43 manatee deaths in Florida alone.

Conservation

All three species of manatee are listed by the World Conservation Union as vulnerable to extinction. However, The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) does not consider the West Indian manatee to be "endangered" anymore, having downgraded its status to "threatened" as of March 2017. They cite improvements to habitat conditions, population growth and reductions of threats as reasoning for the change. The reclassification was met with controversy, with Florida congressman Vern Buchanan and groups such as the Save the Manatee Club and the Center for Biological Diversity expressing concerns that the change would have a detrimental effect on conservation efforts. The new classification will not affect current federal protections. West Indian manatees were originally classified as endangered with the 1967 class of endangered species.

Manatee deaths in the state of Florida nearly doubled in 2021 from 637 (2020) to 1100. Although this number decreased to 800 in 2022, it is likely that current rate of development in Florida, climate change, and decreasing water quality, habitat range, and genetic diversity among this population may lead to reconsideration of the West Indian Manatee as an endangered species. Manatee population in the United States reached a low in the 1970s, during which only a few hundred individuals lived in the nation. As of February 2016, 6,250 manatees were reported swimming in Florida's springs. It is illegal under federal and Florida law to injure or harm a manatee.

There are many conservation programs that have been created to help manatees. Save the Manatee Club is a non-profit group and membership organization that works to protect manatees and their aquatic ecosystems. Founded by Bob Graham, former Florida governor, and singer/songwriter Jimmy Buffett, this is today's leading manatee conservation club.

The MV Freedom Star and MV Liberty Star, ships used by NASA to tow Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters back to Kennedy Space Center, were propelled only by water jets to protect the endangered manatee population that inhabits regions of the Banana River where the ships are based.

Brazil outlawed hunting in 1973 in an effort to preserve the species. Deaths by boat strikes are still common. Although countries are protecting Amazonian manatees in the locations where they are endangered, as of 1994 there were no enforced laws, and the manatees were still being captured throughout their range.

Captivity

There are a number of manatee rehabilitation centers in the United States. These include three government-run critical care facilities in Florida at Lowry Park Zoo, Miami Seaquarium, and SeaWorld Orlando. After initial treatment at these facilities, the manatees are transferred to rehabilitation facilities before release. These include the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Epcot's The Seas, South Florida Museum, and Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park.

The Columbus Zoo was a founding member of the Manatee Rehabilitation Partnership in 2001. Since 1999, the zoo's Manatee Bay facility has helped rehabilitate 20 manatees. The Cincinnati Zoo has rehabilitated and released more than a dozen manatees since 1999.

Manatees can also be viewed in a number of European zoos, such as the Tierpark Berlin and the Nuremberg Zoo in Germany, in ZooParc de Beauval in France, the Aquarium of Genoa in Italy and the Royal Burgers' Zoo in Arnhem, the Netherlands, where manatees have parented offspring. The River Safari at Singapore features seven of them.

The oldest manatee in captivity was Snooty, at the South Florida Museum's Parker Manatee Aquarium in Bradenton, Florida. Born at the Miami Aquarium and Tackle Company on July 21, 1948, Snooty was one of the first recorded captive manatee births. Raised entirely in captivity, Snooty was never to be released into the wild. As such he was the only manatee at the aquarium, and one of only a few captive manatees in the United States that was allowed to interact with human handlers. That made him uniquely suitable for manatee research and education.

Snooty died suddenly two days after his 69th birthday, July 23, 2017, when he was found in an underwater area only used to access plumbing for the exhibit life support system. The South Florida Museum's initial press release stated, “Early indications are that an access panel door that is normally bolted shut had somehow been knocked loose and that Snooty was able to swim in.”

Guyana

Since the 19th century, Georgetown, Guyana has kept West Indian manatees in its botanical garden, and later, its national park. In the 1910s and again in the 1950s, sugar estates in Guyana used manatees to keep their irrigation canals weed-free. Between the 1950s and 1970s, the Georgetown water treatment plant used manatees in their storage canals for the same purpose.

Culture

The manatee has been linked to folklore on mermaids. In West African folklore, they were considered sacred and thought to have been once human. Killing one was taboo and required penance.

In the novel Moby-Dick, Herman Melville distinguishes manatees ("Lamatins", cf. lamantins) from small whales; stating, "I am aware that down to the present time, the fish styled Lamatins and Dugongs (Pig-fish and Sow-fish of the Coffins of Nantucket) are included by many naturalists among the whales. But as these pig-fish are a noisy, contemptible set, mostly lurking in the mouths of rivers, and feeding on wet hay, and especially as they do not spout, I deny their credentials as whales; and have presented them with their passports to quit the Kingdom of Cetology."

A manatee called Wardell appears in the Animal Crossing: New Horizons video game. He is part of a paid downloadable content expansion, managing and selling furniture to the player.

In Rudyard Kipling's The White Seal (one of the stories in The Jungle Book), Sea Cow, about whom the story says that he has only six cervical vertebrae, is a manatee.

See also

References

- "Trichechus Linnaeus 1758 (manatee)". Fossilworks.org. Archived from the original on 2023-06-05. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- West Indian Manatee Facts and Pictures – National Geographic Kids Archived 2011-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. Kids.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- Winger, Jennifer (2000). "What's in a name? Manatees and Dugongs". National Zoological Park. Friends of the National Zoo. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Walters, Martin; Johnson, Jinny (2003). Encyclopedia of Animals. Marks and Spencer. p. 229. ISBN 1-84273-964-6.

- Domning, D.P., 1994, "Paleontology and evolution of sirenians: Status of knowledge and research needs", in Proceedings of the 1st International Manatee and Dugong Research Conference, Gainesville, Florida, 1–5

- "The Florida Manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostrus)". The Amy H Remley Foundation. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- Shoshani, J., ed. (2000). Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-87596-143-6.

- ^ Best, Robin (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 292–298. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- Hautier, Lionel; Weisbecker, V; Sánchez-Villagra, M. R.; Goswami, A; Asher, R. J. (2010). "Skeletal development in sloths and the evolution of mammalian vertebral patterning". PNAS. 107 (44): 18903–18908. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10718903H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010335107. PMC 2973901. PMID 20956304.

- "Sticking Their Necks out for Evolution: Why Sloths and Manatees Have Unusually Long (or Short) Necks". May 6th 2011. Science Daily. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Frietson Galis (1999). "Why do almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae? Developmental constraints, Hox genes and Cancer" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Zoology. 285 (1): 19–26. Bibcode:1999JEZ...285...19G. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19990415)285:1<19::AID-JEZ3>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10327647. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-10.

- "Manatee Anatomy Facts" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-26. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Marsh, Helene. (2011). Ecology and Conservation of the Sirenia : Dugongs and Manatees. O'Shea, Thomas J., Reynolds III, John E. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-15887-9. OCLC 782876868.

- de Souza, Érica Martinha Silva; Freitas, Lucas; da Silva Ramos, Elisa Karen; Selleghin-Veiga, Giovanna; Rachid-Ribeiro, Michelle Carneiro; Silva, Felipe André; Marmontel, Miriam; dos Santos, Fabrício Rodrigues; Laudisoit, Anne; Verheyen, Erik; Domning, Daryl P. (2021-02-11). "The evolutionary history of manatees told by their mitogenomes". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 3564. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3564D. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82390-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7878490. PMID 33574363.

- Domning, Daryl P. (1982). "Evolution of Manatees: A Speculative History". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (3): 599–619. JSTOR 1304394.

- "Manatee FAQ: Behavior". www.savethemanatee.org. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- Gerstein, E. R. (1994). "The manatee mind: Discrimination training for sensory perception testing of West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus)". Marine Mammals. 1: 10–21.

- ^ (Marine Mammal Medicine, 2001, Leslie Dierauf & Frances Gulland, CRC Press)

- Henaut, Yann; Charles, Aviva; Delfour, Fabienne (24 August 2022). "Cognition of the manatee: past research and future developments". Animal Cognition. 25 (5): 1049–1058. doi:10.1007/s10071-022-01676-8. PMID 36002602. S2CID 251808935. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- Jeff Ripple (1999). Manatees and Dugongs of the World. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-1-61060-443-7.

estrous.

- O'Shea, Thomas J.; Lynn B. Poché, Jr. (2006). "Aspects of Underwater Sound Communication in Florida Manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris)". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (6): 1061–1071. doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-A-066R1.1. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 4126883. S2CID 42302073.

- "Manatee Ears Cause for Alarm? | Bird's Underwater". Birds Underwater. 2017-08-01. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- "Animal Info Book: Manatee". Seaworld Parks & Entertainment. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- Lefebvre, Lynn W.; Provancha, Jane A.; Slone, Daniel H.; Kenworthy, W. Judson (2017). "Manatee grazing impacts on a mixed species seagrass bed". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 564: 29–45. Bibcode:2017MEPS..564...29L. doi:10.3354/meps11986. ISSN 0171-8630. JSTOR 24898254. Archived from the original on 2024-01-27. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- Domning, Daryl P. (1981). "Sea Cows and Sea Grasses". Paleobiology. 7 (4): 417–420. Bibcode:1981Pbio....7..417D. doi:10.1017/S009483730002546X. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 2400692. S2CID 88809167. Archived from the original on 2024-01-27. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ^ "Manatee". Journey North. 2003. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- Castellini and Mellish, Michael and Jo-Ann (2016). Marine Mammal Physiology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-4822-4267-6.

- Powell, James (1978). "Evidence for carnivory in manatee (Trichechus manatus)". Journal of Mammalogy. 59 (2): 442. doi:10.2307/1379938. JSTOR 1379938.

- Trials of a Primatologist. – smithsonianmag.com. Accessed March 15, 2008.

- Basu, Rebecca (1 March 2010). "Winter is culprit in manatee death toll". Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. p. 1A. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- Ortiz, RM; Worthy, GA; MacKenzie, DS (July 1998). "Osmoregulation in wild and captive West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus)" (PDF). Physiological Zoology. 71 (4): 449–57. doi:10.1086/515427. hdl:1969.1/182579. PMID 9678505. S2CID 40972754. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- "Manatee (Trichechus manatus) | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". FWS.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-09-13. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- "TRAVELIN' MANATEE FAR FROM HOME AGAIN". Deseret News. 23 August 1995. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Lee, Jennifer 8 (7 August 2006). "Massive Manatee Is Spotted in Hudson River". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Manatee found dead in Tenn. lake". Associated Press. 11 December 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "Dead manatee found along Jersey Shore". ABC7 New York. 2020-02-11. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- Ltd, Copyright Global Sea Temperatures-A.-Connect. "Atlantic City (NJ) Water Temperature | United States | Sea Temperatures". World Sea Temperatures. Archived from the original on 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- US Fish and Wildlife Service (November 14, 2017). "About the Refuge". Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- Keith Morelli (January 7, 2011). "Can manatees survive without warm waters from power plants?". The Tampa Tribune. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- U.S. Marine Mammal Commission 1999

- "Exceptional weather conditions lead to record high manatee count" (Press release). Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. January 20, 2010. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife. "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to Reclassify West Indian Manatee from Endangered to Threatened". www.fws.gov (Press release). Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- "Manatee Synoptic Surveys". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2018. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- (Marmontel, Humphrey, O'Shea 1997, "Population Variability Analysis of the Florida Manatee, 1976–1992", Conserv. biol., 11: 467–481)

- "Record 6,250 Manatees Spotted in Florida Waters". Discovery. February 26, 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Robles Herrejón, Juan Carlos; Morales-Vela, Benjamín; Ortega-Argueta, Alejandro; Pozo, Carmen; Olivera-Gómez, León David (June 2020). "Management effectiveness in marine protected areas for conservation of Antillean manatees on the eastern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 30 (6): 1182–1193. Bibcode:2020ACMFE..30.1182R. doi:10.1002/aqc.3323. ISSN 1052-7613. Archived from the original on 2022-11-21. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- "WaterBear". www.waterbear.com. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- Stock, David. "Manatees discovered in pristine but threatened underwater cave habitat". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2024-02-26. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- "Amazonian Manatee - Facts, Information & Habitat". Archived from the original on 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Keith Diagne, L. (2016). " Trichechus senegalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22104A97168578.

- Luiselli, L.; Akani, G.C.; Ebere, N.; Angelici, F. M.; Amori, G.; Politano, E. (2012). "Macro-habitat preferences by the African manatee and crocodiles – ecological and conservation implications". Web Ecology. 12 (1): 39–48. doi:10.5194/we-12-39-2012.

- Florida boaters killing endangered manatees. Cyber Diver News Network. 11 January 2006

- Gaspard, Joseph C.; Bauer, Gordon B.; Reep, Roger L.; Dziuk, Kimberly; Cardwell, Adrienne; Read, Latoshia; Mann, David A. (2012). "Audiogram and auditory critical ratios of two Florida manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (9): 1442–1447. doi:10.1242/jeb.065649. PMID 22496279. S2CID 11725126. Archived from the original on 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- Manatees hard of hearing Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Scienceagogo.com (1999-07-30). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- Long Term Prospects for Manatee Recovery Look Grim, According To New Data Released By Federal Government Archived 2007-07-12 at the Wayback Machine. Savethemanatee.org (2003-04-29). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ufl.edu Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine. News.ufl.edu (2007-07-03). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- Aipanjiguly, Sampreethi; Jacobson, Susan K.; Flamm, Richard (2003). "Conserving Manatees: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Intentions of Boaters in Tampa Bay, Florida". Conservation Biology. 17 (4): 1098–1105. Bibcode:2003ConBi..17.1098A. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01452.x. S2CID 86770081. Archived from the original on 2021-11-26. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- "Manatee Mortality Statistics". Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. Archived from the original on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- "Manatee Deaths From Boat Strikes Approach Record: Club Asks For Boaters' Urgent Help". Save the Manatee Club. Archived from the original on 2011-02-08. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Flewelling, LJ; Naar, JP; Abbott, JP; Baden, DG; Barros, NB; Bossart, GD; Bottein, MY; Hammond, DG; et al. (9 June 2005). "Brevetoxicosis: Red tides and marine mammal mortalities". Nature. 435 (7043): 755–756. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..755F. doi:10.1038/nature435755a. PMC 2659475. PMID 15944690.

- "Manatee death toll hits record in Florida, 'Red Tide' blamed". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- "Scientists Say Toxin in Red Tide Killed Scores of Manatees". New York Times. July 5, 1996. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "Mystery epidemic killing manatees". Local & State. April 9, 1996. p. 38. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "2023 Bloom". Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 2024-04-04. Retrieved 2024-04-09.

- Greg Allen (2 Dec 2021). "Manatees are starving in Florida. Wildlife agencies are scrambling to save them". NPR. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- Amanda Jackson (17 Feb 2022). "Florida wildlife officials are distributing 3,000 pounds of lettuce a day to save starving manatees". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- Help End Manatee Harassment in Citrus County, Florida! Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. Savethemanatee.org. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- St. Petersburg Times – Manatee Abuse Caught on Tape Archived 2009-06-01 at the Wayback Machine. Sptimes.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- Tribune, Chicago (29 February 2016). "Monarch butterfly, manatee populations are on a big rebound". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- "January 2016 Preliminary Manatee Mortality Table by County" (PDF). January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- Wang, Amy B. (March 31, 2017). "Manatees are no longer listed as endangered. Should we celebrate or fret?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "Endangered Species | Class of 1967". www.fws.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-05-24. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION MARINE MAMMAL PATHOBIOLOGY LABORATORY Preliminary 2022 Manatee Mortality Table by County" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-24. Retrieved 2023-03-24.

- Jones Jr., Robert C. (February 2, 2022). "NO LONGER ENDANGERED, MANATEES NOW FACE ANOTHER CRISIS". Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- "Manatee reclassified from endangered to threatened as habitat improves and population expands - existing federal protections remain in place". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 2020-05-29. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- "Record-breaking number of manatees counted during annual winter survey". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- "Save The Manatees". Save The Manatees. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Fairclough, Caty. "From Mermaids to Manatees: the Myth and the Reality | Smithsonian Ocean". ocean.si.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- "New Study Shows Impact of Watercraft on Manatees". Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- Weber Rosas, F.C. (June 1994). "Biology, conservation, and status of the Amazonian Manatee Trichechus inunguis". Mammal Review. 24 (2): 49–59. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1994.tb00134.x.

- "Manatee Rescue, Rehabilitation and Release Program". Archived from the original on 2017-01-01. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- "Global Impact - Project". Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- "Rescue, Rehabilitation and Release of Florida Manatees". Archived from the original on 2017-01-01. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- "Adventure in the mangrove forest". Archived from the original on 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- Tan, Sue-Ann (13 March 2013). "Manatees move into world's largest freshwater aquarium at River Safari". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- Aronson, Claire. "Guinness World Records names Snooty of Bradenton as 'Oldest Manatee in Captivity'". bradenton.com. Bradenton Herald. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Snooty the Manatee. South Florida Museum. ISBN 978-1-56944-441-2.

- "Oldest living manatee in captivity dies a day after celebrating 69th birthday". 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-07-23. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- "Abary Creek manatees under threat". Stabroek News. 30 September 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

there are 23 manatees between the Botanical Gardens and the National Park. They have been there for more than 129 years, and reports are that they came from the Abary Creek.

- National Science Research Council (Guyana). (1974). An International Centre for Manatee Research. Georgetown, Guyana: National Academies. p. 13.

- National Research Council (2002). Making Aquatic Weeds Useful. The Minerva Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-89499-180-6.

In the Georgetown Water and Sewerage Works, two manatees were introduced in 1952 to a canal In the 24 years since then, manatees have been used to keep this water (the city's municipal supply) weed-free.

- Cooper, JC (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. p. 157. ISBN 1-85538-118-4.

- Melville, Herman (1851). "Footnote, Chapter 32 - Cetology". Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. Richard Bentley.

- Fahey, Mike (18 October 2021). "Animal Crossing Fans Are Deeply In Love With Wardell The Manatee". Kotaku. G/O Media. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

Further reading

- Hall, Alice J. (September 1984). "Man and Manatee: Can We Live Together?". National Geographic. Vol. 166, no. 3. pp. 400–418. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

- Save the Manatee Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Murie, James On the Form and Structure of the Manatee (Manatus americanus), (1872) London, Zoological Society of London Year

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Archived 2018-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Reuters: Florida manatees may lose endangered status Archived 2020-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- A website with many manatee photos

- USGS/SESC Sirenia Project Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Bibliography and Index of the Sirenia and Desmostylia – Dr. Domning's authoritative manatee research bibliography

| Extant Sirenia species by family | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Dugongidae (Dugongs) |

| ||

| Trichechidae (Manatees) |

| ||

| Category | |||

| Sirenian genera | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sirenia |

|  | ||||||||||||||||||||