| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (July 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Mechanism design, sometimes called implementation theory or institution design, is a branch of economics, social choice, and game theory that deals with designing game forms (or mechanisms) to implement a given social choice function. Because it starts with the end of the game (an optimal result) and then works backwards to find a game that implements it, it is sometimes described as reverse game theory.

Mechanism design has broad applications, including traditional domains of economics such as market design, but also political science (through voting theory) and even networked systems (such as in inter-domain routing).

Mechanism design studies solution concepts for a class of private-information games. Leonid Hurwicz explains that "in a design problem, the goal function is the main given, while the mechanism is the unknown. Therefore, the design problem is the inverse of traditional economic theory, which is typically devoted to the analysis of the performance of a given mechanism."

The 2007 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to Leonid Hurwicz, Eric Maskin, and Roger Myerson "for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory." The related works of William Vickrey that established the field earned him the 1996 Nobel prize.

Description

One person, called the "principal", would like to condition his behavior on information privately known to the players of a game. For example, the principal would like to know the true quality of a used car a salesman is pitching. He cannot learn anything simply by asking the salesman, because it is in the salesman's interest to distort the truth. However, in mechanism design, the principal does have one advantage: He may design a game whose rules influence others to act the way he would like.

Without mechanism design theory, the principal's problem would be difficult to solve. He would have to consider all the possible games and choose the one that best influences other players' tactics. In addition, the principal would have to draw conclusions from agents who may lie to him. Thanks to the revelation principle, the principal only needs to consider games in which agents truthfully report their private information.

Foundations

Mechanism

A game of mechanism design is a game of private information in which one of the agents, called the principal, chooses the payoff structure. Following Harsanyi (1967), the agents receive secret "messages" from nature containing information relevant to payoffs. For example, a message may contain information about their preferences or the quality of a good for sale. We call this information the agent's "type" (usually noted and accordingly the space of types ). Agents then report a type to the principal (usually noted with a hat ) that can be a strategic lie. After the report, the principal and the agents are paid according to the payoff structure the principal chose.

The timing of the game is:

- The principal commits to a mechanism that grants an outcome as a function of reported type

- The agents report, possibly dishonestly, a type profile

- The mechanism is executed (agents receive outcome )

In order to understand who gets what, it is common to divide the outcome into a goods allocation and a money transfer, where stands for an allocation of goods rendered or received as a function of type, and stands for a monetary transfer as a function of type.

As a benchmark the designer often defines what should happen under full information. Define a social choice function mapping the (true) type profile directly to the allocation of goods received or rendered,

In contrast a mechanism maps the reported type profile to an outcome (again, both a goods allocation and a money transfer )

Revelation principle

Main article: Revelation principleA proposed mechanism constitutes a Bayesian game (a game of private information), and if it is well-behaved the game has a Bayesian Nash equilibrium. At equilibrium agents choose their reports strategically as a function of type

It is difficult to solve for Bayesian equilibria in such a setting because it involves solving for agents' best-response strategies and for the best inference from a possible strategic lie. Thanks to a sweeping result called the revelation principle, no matter the mechanism a designer can confine attention to equilibria in which agents truthfully report type. The revelation principle states: "To every Bayesian Nash equilibrium there corresponds a Bayesian game with the same equilibrium outcome but in which players truthfully report type."

This is extremely useful. The principle allows one to solve for a Bayesian equilibrium by assuming all players truthfully report type (subject to an incentive compatibility constraint). In one blow it eliminates the need to consider either strategic behavior or lying.

Its proof is quite direct. Assume a Bayesian game in which the agent's strategy and payoff are functions of its type and what others do, . By definition agent i's equilibrium strategy is Nash in expected utility:

Simply define a mechanism that would induce agents to choose the same equilibrium. The easiest one to define is for the mechanism to commit to playing the agents' equilibrium strategies for them.

Under such a mechanism the agents of course find it optimal to reveal type since the mechanism plays the strategies they found optimal anyway. Formally, choose such that

Implementability

Main article: Implementability (mechanism design)The designer of a mechanism generally hopes either

- to design a mechanism that "implements" a social choice function

- to find the mechanism that maximizes some value criterion (e.g. profit)

To implement a social choice function is to find some transfer function that motivates agents to pick . Formally, if the equilibrium strategy profile under the mechanism maps to the same goods allocation as a social choice function,

we say the mechanism implements the social choice function.

Thanks to the revelation principle, the designer can usually find a transfer function to implement a social choice by solving an associated truthtelling game. If agents find it optimal to truthfully report type,

we say such a mechanism is truthfully implementable. The task is then to solve for a truthfully implementable and impute this transfer function to the original game. An allocation is truthfully implementable if there exists a transfer function such that

which is also called the incentive compatibility (IC) constraint.

In applications, the IC condition is the key to describing the shape of in any useful way. Under certain conditions it can even isolate the transfer function analytically. Additionally, a participation (individual rationality) constraint is sometimes added if agents have the option of not playing.

Necessity

Consider a setting in which all agents have a type-contingent utility function . Consider also a goods allocation that is vector-valued and size (which permits number of goods) and assume it is piecewise continuous with respect to its arguments.

The function is implementable only if

whenever and and x is continuous at . This is a necessary condition and is derived from the first- and second-order conditions of the agent's optimization problem assuming truth-telling.

Its meaning can be understood in two pieces. The first piece says the agent's marginal rate of substitution (MRS) increases as a function of the type,

In short, agents will not tell the truth if the mechanism does not offer higher agent types a better deal. Otherwise, higher types facing any mechanism that punishes high types for reporting will lie and declare they are lower types, violating the truthtelling incentive-compatibility constraint. The second piece is a monotonicity condition waiting to happen,

which, to be positive, means higher types must be given more of the good.

There is potential for the two pieces to interact. If for some type range the contract offered less quantity to higher types , it is possible the mechanism could compensate by giving higher types a discount. But such a contract already exists for low-type agents, so this solution is pathological. Such a solution sometimes occurs in the process of solving for a mechanism. In these cases it must be "ironed". In a multiple-good environment it is also possible for the designer to reward the agent with more of one good to substitute for less of another (e.g. butter for margarine). Multiple-good mechanisms are an area of continuing research in mechanism design.

Sufficiency

Mechanism design papers usually make two assumptions to ensure implementability:

This is known by several names: the single-crossing condition, the sorting condition and the Spence–Mirrlees condition. It means the utility function is of such a shape that the agent's MRS is increasing in type.

This is a technical condition bounding the rate of growth of the MRS.

These assumptions are sufficient to provide that any monotonic is implementable (a exists that can implement it). In addition, in the single-good setting the single-crossing condition is sufficient to provide that only a monotonic is implementable, so the designer can confine his search to a monotonic .

Highlighted results

Revenue equivalence theorem

Main article: Revenue equivalenceVickrey (1961) gives a celebrated result that any member of a large class of auctions assures the seller of the same expected revenue and that the expected revenue is the best the seller can do. This is the case if

- The buyers have identical valuation functions (which may be a function of type)

- The buyers' types are independently distributed

- The buyers types are drawn from a continuous distribution

- The type distribution bears the monotone hazard rate property

- The mechanism sells the good to the buyer with the highest valuation

The last condition is crucial to the theorem. An implication is that for the seller to achieve higher revenue he must take a chance on giving the item to an agent with a lower valuation. Usually this means he must risk not selling the item at all.

Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanisms

Main article: Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanismThe Vickrey (1961) auction model was later expanded by Clarke (1971) and Groves to treat a public choice problem in which a public project's cost is borne by all agents, e.g. whether to build a municipal bridge. The resulting "Vickrey–Clarke–Groves" mechanism can motivate agents to choose the socially efficient allocation of the public good even if agents have privately known valuations. In other words, it can solve the "tragedy of the commons"—under certain conditions, in particular quasilinear utility or if budget balance is not required.

Consider a setting in which number of agents have quasilinear utility with private valuations where the currency is valued linearly. The VCG designer designs an incentive compatible (hence truthfully implementable) mechanism to obtain the true type profile, from which the designer implements the socially optimal allocation

The cleverness of the VCG mechanism is the way it motivates truthful revelation. It eliminates incentives to misreport by penalizing any agent by the cost of the distortion he causes. Among the reports the agent may make, the VCG mechanism permits a "null" report saying he is indifferent to the public good and cares only about the money transfer. This effectively removes the agent from the game. If an agent does choose to report a type, the VCG mechanism charges the agent a fee if his report is pivotal, that is if his report changes the optimal allocation x so as to harm other agents. The payment is calculated

which sums the distortion in the utilities of the other agents (and not his own) caused by one agent reporting.

Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem

Main article: Gibbard–Satterthwaite theoremGibbard (1973) and Satterthwaite (1975) give an impossibility result similar in spirit to Arrow's impossibility theorem. For a very general class of games, only "dictatorial" social choice functions can be implemented.

A social choice function f() is dictatorial if one agent always receives his most-favored goods allocation,

The theorem states that under general conditions any truthfully implementable social choice function must be dictatorial if,

- X is finite and contains at least three elements

- Preferences are rational

Myerson–Satterthwaite theorem

Main article: Myerson–Satterthwaite theoremMyerson and Satterthwaite (1983) show there is no efficient way for two parties to trade a good when they each have secret and probabilistically varying valuations for it, without the risk of forcing one party to trade at a loss. It is among the most remarkable negative results in economics—a kind of negative mirror to the fundamental theorems of welfare economics.

Shapley value

Main article: Shapley valuePhillips and Marden (2018) proved that for cost-sharing games with concave cost functions, the optimal cost-sharing rule that firstly optimizes the worst-case inefficiencies in a game (the price of anarchy), and then secondly optimizes the best-case outcomes (the price of stability), is precisely the Shapley value cost-sharing rule. A symmetrical statement is similarly valid for utility-sharing games with convex utility functions.

Price discrimination

Mirrlees (1971) introduces a setting in which the transfer function t() is easy to solve for. Due to its relevance and tractability it is a common setting in the literature. Consider a single-good, single-agent setting in which the agent has quasilinear utility with an unknown type parameter

and in which the principal has a prior CDF over the agent's type . The principal can produce goods at a convex marginal cost c(x) and wants to maximize the expected profit from the transaction

subject to IC and IR conditions

The principal here is a monopolist trying to set a profit-maximizing price scheme in which it cannot identify the type of the customer. A common example is an airline setting fares for business, leisure and student travelers. Due to the IR condition it has to give every type a good enough deal to induce participation. Due to the IC condition it has to give every type a good enough deal that the type prefers its deal to that of any other.

A trick given by Mirrlees (1971) is to use the envelope theorem to eliminate the transfer function from the expectation to be maximized,

Integrating,

where is some index type. Replacing the incentive-compatible in the maximand,

after an integration by parts. This function can be maximized pointwise.

Because is incentive-compatible already the designer can drop the IC constraint. If the utility function satisfies the Spence–Mirrlees condition then a monotonic function exists. The IR constraint can be checked at equilibrium and the fee schedule raised or lowered accordingly. Additionally, note the presence of a hazard rate in the expression. If the type distribution bears the monotone hazard ratio property, the FOC is sufficient to solve for t(). If not, then it is necessary to check whether the monotonicity constraint (see sufficiency, above) is satisfied everywhere along the allocation and fee schedules. If not, then the designer must use Myerson ironing.

Myerson ironing

In some applications the designer may solve the first-order conditions for the price and allocation schedules yet find they are not monotonic. For example, in the quasilinear setting this often happens when the hazard ratio is itself not monotone. By the Spence–Mirrlees condition the optimal price and allocation schedules must be monotonic, so the designer must eliminate any interval over which the schedule changes direction by flattening it.

Intuitively, what is going on is the designer finds it optimal to bunch certain types together and give them the same contract. Normally the designer motivates higher types to distinguish themselves by giving them a better deal. If there are insufficiently few higher types on the margin the designer does not find it worthwhile to grant lower types a concession (called their information rent) in order to charge higher types a type-specific contract.

Consider a monopolist principal selling to agents with quasilinear utility, the example above. Suppose the allocation schedule satisfying the first-order conditions has a single interior peak at and a single interior trough at , illustrated at right.

- Following Myerson (1981) flatten it by choosing satisfying where is the inverse function of x mapping to and is the inverse function of x mapping to . That is, returns a before the interior peak and returns a after the interior trough.

- If the nonmonotonic region of borders the edge of the type space, simply set the appropriate function (or both) to the boundary type. If there are multiple regions, see a textbook for an iterative procedure; it may be that more than one troughs should be ironed together.

Proof

The proof uses the theory of optimal control. It considers the set of intervals in the nonmonotonic region of over which it might flatten the schedule. It then writes a Hamiltonian to obtain necessary conditions for a within the intervals

- that does satisfy monotonicity

- for which the monotonicity constraint is not binding on the boundaries of the interval

Condition two ensures that the satisfying the optimal control problem reconnects to the schedule in the original problem at the interval boundaries (no jumps). Any satisfying the necessary conditions must be flat because it must be monotonic and yet reconnect at the boundaries.

As before maximize the principal's expected payoff, but this time subject to the monotonicity constraint

and use a Hamiltonian to do it, with shadow price

where is a state variable and the control. As usual in optimal control the costate evolution equation must satisfy

Taking advantage of condition 2, note the monotonicity constraint is not binding at the boundaries of the interval,

meaning the costate variable condition can be integrated and also equals 0

The average distortion of the principal's surplus must be 0. To flatten the schedule, find an such that its inverse image maps to a interval satisfying the condition above.

See also

- Algorithmic mechanism design

- Alvin E. Roth – Nobel Prize, market design

- Assignment problem

- Budget-feasible mechanism

- Contract theory

- Implementation theory

- Incentive compatibility

- Revelation principle

- Smart market

- Metagame

Notes

- "Journal of Mechanism and Institution Design". www.mechanism-design.org. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Penna, Paolo; Ventre, Carmine (July 2014). "Optimal collusion-resistant mechanisms with verification". Games and Economic Behavior. 86: 491–509. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2012.09.002. ISSN 0899-8256.

- L. Hurwicz & S. Reiter (2006), Designing Economic Mechanisms, p. 30

- "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2007" (Press release). Nobel Foundation. October 15, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- In unusual circumstances some truth-telling games have more equilibria than the Bayesian game they mapped from. See Fudenburg-Tirole Ch. 7.2 for some references.

- Phillips, Matthew; Marden, Jason R. (July 2018). "Design Tradeoffs in Concave Cost-Sharing Games". IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 63 (7): 2242–2247. doi:10.1109/tac.2017.2765299. ISSN 0018-9286. S2CID 45923961.

References

- Clarke, Edward H. (1971). "Multipart Pricing of Public Goods" (PDF). Public Choice. 11 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1007/BF01726210. JSTOR 30022651. S2CID 154860771. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- Gibbard, Allan (1973). "Manipulation of voting schemes: A general result" (PDF). Econometrica. 41 (4): 587–601. doi:10.2307/1914083. JSTOR 1914083. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-23. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- Groves, Theodore (1973). "Incentives in Teams" (PDF). Econometrica. 41 (4): 617–631. doi:10.2307/1914085. JSTOR 1914085.

- Harsanyi, John C. (1967). "Games with incomplete information played by "Bayesian" players, I-III. part I. The Basic Model". Management Science. 14 (3): 159–182. doi:10.1287/mnsc.14.3.159. JSTOR 2628393.

- Mirrlees, J. A. (1971). "An Exploration in the Theory of Optimum Income Taxation" (PDF). Review of Economic Studies. 38 (2): 175–208. doi:10.2307/2296779. JSTOR 2296779. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- Myerson, Roger B.; Satterthwaite, Mark A. (1983). "Efficient Mechanisms for Bilateral Trading" (PDF). Journal of Economic Theory. 29 (2): 265–281. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(83)90048-0. hdl:10419/220829. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-08-12.

- Satterthwaite, Mark Allen (1975). "Strategy-proofness and Arrow's conditions: Existence and correspondence theorems for voting procedures and social welfare functions". Journal of Economic Theory. 10 (2): 187–217. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.471.9842. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(75)90050-2.

- Vickrey, William (1961). "Counterspeculation, Auctions, and Competitive Sealed Tenders" (PDF). The Journal of Finance. 16 (1): 8–37. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1961.tb02789.x.

Further reading

- Chapter 7 of Fudenberg, Drew; Tirole, Jean (1991), Game Theory, Boston: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-06141-4. A standard text for graduate game theory.

- Chapter 23 of Mas-Colell; Whinston; Green (1995), Microeconomic Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-507340-9. A standard text for graduate microeconomics.

- Milgrom, Paul (2004), Putting Auction Theory to Work, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55184-7. Applications of mechanism design principles in the context of auctions.

- Noam Nisan. A Google tech talk on mechanism design.

- Legros, Patrick; Cantillon, Estelle (2007). "What is mechanism design and why does it matter for policy-making?". Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Roger B. Myerson (2008), "Mechanism Design", The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, Abstract.

- Diamantaras, Dimitrios (2009), A Toolbox for Economic Design, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-61060-6. A graduate text specifically focused on mechanism design.

External links

- Eric Maskin "Nobel Prize Lecture" delivered on 8 December 2007 at Aula Magna, Stockholm University.

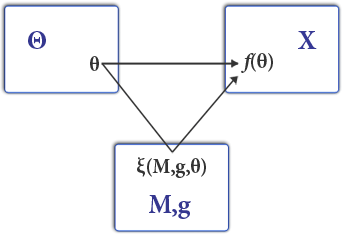

depicts the type space and the upper-right space X the space of outcomes. The

depicts the type space and the upper-right space X the space of outcomes. The  maps a type profile to an outcome. In games of mechanism design, agents send messages

maps a type profile to an outcome. In games of mechanism design, agents send messages  in a game environment

in a game environment  . The equilibrium in the game

. The equilibrium in the game  can be designed to implement some social choice function

can be designed to implement some social choice function  and accordingly the space of types

and accordingly the space of types  ) that can be a strategic lie. After the report, the principal and the agents are paid according to the payoff structure the principal chose.

) that can be a strategic lie. After the report, the principal and the agents are paid according to the payoff structure the principal chose.

that grants an outcome

that grants an outcome  as a function of reported type

as a function of reported type )

) where

where  stands for an allocation of goods rendered or received as a function of type, and

stands for an allocation of goods rendered or received as a function of type, and  stands for a monetary transfer as a function of type.

stands for a monetary transfer as a function of type.

. By definition agent i's equilibrium strategy

. By definition agent i's equilibrium strategy  is Nash in expected utility:

is Nash in expected utility:

such that

such that

that motivates agents to pick

that motivates agents to pick

is truthfully implementable if there exists a transfer function

is truthfully implementable if there exists a transfer function

. Consider also a goods allocation

. Consider also a goods allocation  (which permits

(which permits

and

and  and x is continuous at

and x is continuous at

, it is possible the mechanism could compensate by giving higher types a discount. But such a contract already exists for low-type agents, so this solution is pathological. Such a solution sometimes occurs in the process of solving for a mechanism. In these cases it must be "

, it is possible the mechanism could compensate by giving higher types a discount. But such a contract already exists for low-type agents, so this solution is pathological. Such a solution sometimes occurs in the process of solving for a mechanism. In these cases it must be "

number of agents have quasilinear utility with private valuations

number of agents have quasilinear utility with private valuations  where the currency

where the currency

. The principal can produce goods at a convex marginal cost c(x) and wants to maximize the expected profit from the transaction

. The principal can produce goods at a convex marginal cost c(x) and wants to maximize the expected profit from the transaction

is some index type. Replacing the incentive-compatible

is some index type. Replacing the incentive-compatible  in the maximand,

in the maximand,

is incentive-compatible already the designer can drop the IC constraint. If the utility function satisfies the Spence–Mirrlees condition then a monotonic

is incentive-compatible already the designer can drop the IC constraint. If the utility function satisfies the Spence–Mirrlees condition then a monotonic  and a single interior trough at

and a single interior trough at  , illustrated at right.

, illustrated at right.

where

where  is the inverse function of x mapping to

is the inverse function of x mapping to  and

and  is the inverse function of x mapping to

is the inverse function of x mapping to  . That is,

. That is,  returns a

returns a  returns a

returns a  function (or both) to the boundary type. If there are multiple regions, see a textbook for an iterative procedure; it may be that more than one troughs should be ironed together.

function (or both) to the boundary type. If there are multiple regions, see a textbook for an iterative procedure; it may be that more than one troughs should be ironed together. in the nonmonotonic region of

in the nonmonotonic region of

the control. As usual in optimal control the costate evolution equation must satisfy

the control. As usual in optimal control the costate evolution equation must satisfy