| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Mohr–Coulomb theory" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Part of a series on | |||||||

| Continuum mechanics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fick's laws of diffusion | |||||||

Laws

|

|||||||

| Solid mechanics | |||||||

Fluid mechanics

|

|||||||

Rheology

|

|||||||

| Scientists | |||||||

Mohr–Coulomb theory is a mathematical model (see yield surface) describing the response of brittle materials such as concrete, or rubble piles, to shear stress as well as normal stress. Most of the classical engineering materials follow this rule in at least a portion of their shear failure envelope. Generally the theory applies to materials for which the compressive strength far exceeds the tensile strength.

In geotechnical engineering it is used to define shear strength of soils and rocks at different effective stresses.

In structural engineering it is used to determine failure load as well as the angle of fracture of a displacement fracture in concrete and similar materials. Coulomb's friction hypothesis is used to determine the combination of shear and normal stress that will cause a fracture of the material. Mohr's circle is used to determine which principal stresses will produce this combination of shear and normal stress, and the angle of the plane in which this will occur. According to the principle of normality the stress introduced at failure will be perpendicular to the line describing the fracture condition.

It can be shown that a material failing according to Coulomb's friction hypothesis will show the displacement introduced at failure forming an angle to the line of fracture equal to the angle of friction. This makes the strength of the material determinable by comparing the external mechanical work introduced by the displacement and the external load with the internal mechanical work introduced by the strain and stress at the line of failure. By conservation of energy the sum of these must be zero and this will make it possible to calculate the failure load of the construction.

A common improvement of this model is to combine Coulomb's friction hypothesis with Rankine's principal stress hypothesis to describe a separation fracture. An alternative view derives the Mohr-Coulomb criterion as extension failure.

History of the development

The Mohr–Coulomb theory is named in honour of Charles-Augustin de Coulomb and Christian Otto Mohr. Coulomb's contribution was a 1776 essay entitled "Essai sur une application des règles des maximis et minimis à quelques problèmes de statique relatifs à l'architecture" . Mohr developed a generalised form of the theory around the end of the 19th century. As the generalised form affected the interpretation of the criterion, but not the substance of it, some texts continue to refer to the criterion as simply the 'Coulomb criterion'.

Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion

The Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion represents the linear envelope that is obtained from a plot of the shear strength of a material versus the applied normal stress. This relation is expressed as

where is the shear strength, is the normal stress, is the intercept of the failure envelope with the axis, and is the slope of the failure envelope. The quantity is often called the cohesion and the angle is called the angle of internal friction. Compression is assumed to be positive in the following discussion. If compression is assumed to be negative then should be replaced with .

If , the Mohr–Coulomb criterion reduces to the Tresca criterion. On the other hand, if the Mohr–Coulomb model is equivalent to the Rankine model. Higher values of are not allowed.

From Mohr's circle we have where and is the maximum principal stress and is the minimum principal stress.

Therefore, the Mohr–Coulomb criterion may also be expressed as

This form of the Mohr–Coulomb criterion is applicable to failure on a plane that is parallel to the direction.

Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion in three dimensions

The Mohr–Coulomb criterion in three dimensions is often expressed as

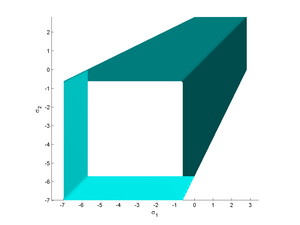

The Mohr–Coulomb failure surface is a cone with a hexagonal cross section in deviatoric stress space.

The expressions for and can be generalized to three dimensions by developing expressions for the normal stress and the resolved shear stress on a plane of arbitrary orientation with respect to the coordinate axes (basis vectors). If the unit normal to the plane of interest is

where are three orthonormal unit basis vectors, and if the principal stresses are aligned with the basis vectors , then the expressions for are

The Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion can then be evaluated using the usual expression for the six planes of maximum shear stress.

Derivation of normal and shear stress on a plane Let the unit normal to the plane of interest be where are three orthonormal unit basis vectors. Then the traction vector on the plane is given by

The magnitude of the traction vector is given by

Then the magnitude of the stress normal to the plane is given by

The magnitude of the resolved shear stress on the plane is given by In terms of components, we have

If the principal stresses are aligned with the basis vectors , then the expressions for are

|

|

Mohr–Coulomb failure surface in Haigh–Westergaard space

The Mohr–Coulomb failure (yield) surface is often expressed in Haigh–Westergaad coordinates. For example, the function can be expressed as

Alternatively, in terms of the invariants we can write

where

Derivation of alternative forms of Mohr–Coulomb yield function We can express the yield function as

The Haigh–Westergaard invariants are related to the principal stresses by

Plugging into the expression for the Mohr–Coulomb yield function gives us

Using trigonometric identities for the sum and difference of cosines and rearrangement gives us the expression of the Mohr–Coulomb yield function in terms of .

We can express the yield function in terms of by using the relations and straightforward substitution.

Mohr–Coulomb yield and plasticity

The Mohr–Coulomb yield surface is often used to model the plastic flow of geomaterials (and other cohesive-frictional materials). Many such materials show dilatational behavior under triaxial states of stress which the Mohr–Coulomb model does not include. Also, since the yield surface has corners, it may be inconvenient to use the original Mohr–Coulomb model to determine the direction of plastic flow (in the flow theory of plasticity).

A common approach is to use a non-associated plastic flow potential that is smooth. An example of such a potential is the function

where is a parameter, is the value of when the plastic strain is zero (also called the initial cohesion yield stress), is the angle made by the yield surface in the Rendulic plane at high values of (this angle is also called the dilation angle), and is an appropriate function that is also smooth in the deviatoric stress plane.

Typical values of cohesion and angle of internal friction

Cohesion (alternatively called the cohesive strength) and friction angle values for rocks and some common soils are listed in the tables below.

| Material | Cohesive strength in kPa | Cohesive strength in psi |

|---|---|---|

| Rock | 10000 | 1450 |

| Silt | 75 | 10 |

| Clay | 10 to 200 | 1.5 to 30 |

| Very soft clay | 0 to 48 | 0 to 7 |

| Soft clay | 48 to 96 | 7 to 14 |

| Medium clay | 96 to 192 | 14 to 28 |

| Stiff clay | 192 to 384 | 28 to 56 |

| Very stiff clay | 384 to 766 | 28 to 110 |

| Hard clay | > 766 | > 110 |

| Material | Friction angle in degrees |

|---|---|

| Rock | 30° |

| Sand | 30° to 45° |

| Gravel | 35° |

| Silt | 26° to 35° |

| Clay | 20° |

| Loose sand | 30° to 35° |

| Medium sand | 40° |

| Dense sand | 35° to 45° |

| Sandy gravel | > 34° to 48° |

See also

- 3-D elasticity

- Hoek–Brown failure criterion

- Byerlee's law

- Lateral earth pressure

- von Mises stress

- Yield (engineering)

- Drucker Prager yield criterion — a smooth version of the M–C yield criterion

- Lode coordinates

- Bigoni–Piccolroaz yield criterion

References

- Juvinal, Robert C. & Marshek, Kurt .; Fundamentals of machine component design. – 2nd ed., 1991, pp. 217, ISBN 0-471-62281-8

- ^ Coulomb, C. A. (1776). Essai sur une application des regles des maximis et minimis a quelquels problemesde statique relatifs, a la architecture. Mem. Acad. Roy. Div. Sav., vol. 7, pp. 343–387.

- Staat, M. (2021) An extension strain type Mohr–Coulomb criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng., vol. 54, pp. 6207–6233. DOI: 10.1007/s00603-021-02608-7.

- AMIR R. KHOEI; Computational Plasticity in Powder Forming Processes; Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2005; 449 pp.

- Yu, Mao-hong (2002-05-01). "Advances in strength theories for materials under complex stress state in the 20th Century". Applied Mechanics Reviews. 55 (3): 169–218. Bibcode:2002ApMRv..55..169Y. doi:10.1115/1.1472455. ISSN 0003-6900.

- NIELS SAABYE OTTOSEN and MATTI RISTINMAA; The Mechanics of Constitutive Modeling; Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 2005; pp. 165ff.

- Coulomb, C. A. (1776). Essai sur une application des regles des maximis et minimis a quelquels problemesde statique relatifs, a la architecture. Mem. Acad. Roy. Div. Sav., vol. 7, pp. 343–387.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20061008230404/http://fbe.uwe.ac.uk/public/geocal/SoilMech/basic/soilbasi.htm

- http://www.civil.usyd.edu.au/courses/civl2410/earth_pressures_rankine.doc

| Structural engineering | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic analysis | |||||||

| Static analysis | |||||||

| Structural elements |

| ||||||

| Theories | |||||||

is the shear strength,

is the shear strength,  is the normal stress,

is the normal stress,  is the intercept of the failure envelope with the

is the intercept of the failure envelope with the  is the slope of the failure envelope. The quantity

is the slope of the failure envelope. The quantity  is called the angle of internal friction. Compression is assumed to be positive in the following discussion. If compression is assumed to be negative then

is called the angle of internal friction. Compression is assumed to be positive in the following discussion. If compression is assumed to be negative then  .

.

, the Mohr–Coulomb criterion reduces to the

, the Mohr–Coulomb criterion reduces to the  the Mohr–Coulomb model is equivalent to the Rankine model. Higher values of

the Mohr–Coulomb model is equivalent to the Rankine model. Higher values of  where

where

and

and  is the maximum principal stress and

is the maximum principal stress and  is the minimum principal stress.

is the minimum principal stress.

direction.

direction.

are three orthonormal unit basis vectors, and if the principal stresses

are three orthonormal unit basis vectors, and if the principal stresses  are aligned with the basis vectors

are aligned with the basis vectors  , then the expressions for

, then the expressions for  are

are

In terms of components, we have

In terms of components, we have

-plane for

-plane for

-plane for

-plane for  can be expressed as

can be expressed as

we can write

we can write

.

.

by using the relations

by using the relations

and straightforward substitution.

and straightforward substitution.

is a parameter,

is a parameter,  is the value of

is the value of  is the angle made by the yield surface in the Rendulic plane at high values of

is the angle made by the yield surface in the Rendulic plane at high values of  (this angle is also called the dilation angle), and

(this angle is also called the dilation angle), and  is an appropriate function that is also smooth in the deviatoric stress plane.

is an appropriate function that is also smooth in the deviatoric stress plane.