Page version status

This is an accepted version of this page

A hookah (also see other names), shisha, or waterpipe is a single- or multi-stemmed instrument for heating or vaporizing and then smoking either tobacco, flavored tobacco (often muʽassel), or sometimes cannabis, hashish and opium. The smoke is passed through a water basin—often glass-based—before inhalation.

The major health risks of smoking tobacco, cannabis, opium and other drugs through a hookah include exposure to toxic chemicals, carcinogens and heavy metals that are not filtered out by the water, alongside those related to the transmission of infectious diseases and pathogenic bacteria when hookahs are shared. Hookah and waterpipe use is a global public health concern, with high rates of use in the populations of the Middle East and North Africa as well as in young people in the United States, Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia.

The hookah or waterpipe was invented by Abul-Fath Gilani, a Persian physician of Akbar, in the Indian city of Fatehpur Sikri during Mughal India; the hookah spread from the Indian subcontinent to Persia first where the mechanism was modified to its current shape and then to the Ottoman empire. Alternatively, it could have originated in the Safavid dynasty of Persia, from where it eventually spread to the Indian subcontinent.

Despite tobacco and drug use being considered a taboo when the hookah was first conceived, its use became increasingly popular among nobility and subsequently widely accepted. Burned tobacco is increasingly being replaced by vaporizing flavored tobacco. Still the original hookah is often used in rural South Asia, which continues to use tumbak (a pure and coarse form of unflavored tobacco leaves) and smoked by burning it directly with charcoal. While this method delivers a much higher content of tobacco and nicotine, it also incurs more adverse health effects compared to vaporizing hookahs.

The word hookah is a derivative of "huqqa", a Hindustani word, of Arabic origin (derived from حُقَّة ḥuqqa, "casket, bottle, water pipe"). Outside its native region, hookah smoking has gained popularity throughout the world, especially among younger people.

Names and etymology

In the Indian subcontinent, the Hindustani word huqqa (Devanagari: हुक़्क़ा, Nastaleeq: حقّہ) is used and is the origin of the English word "hookah". The widespread use of the Indian word "hookah" in the English language is a result of the colonization in British India (1858–1947), when large numbers of expatriate Britons first sampled the water pipe. William Hickey, shortly after arriving in Calcutta, India, in 1775, wrote in his Memoirs:

- The most highly-dressed and splendid hookah was prepared for me. I tried it, but did not like it. As after several trials I still found it disagreeable, I with much gravity requested to know whether it was indispensably necessary that I should become a smoker, which was answered with equal gravity, "Undoubtedly it is, for you might as well be out of the world as out of the fashion. Here everybody uses a hookah, and it is impossible to get on without ... have frequently heard men declare they would much rather be deprived of their dinner than their hookah."

Arabic أرجيلة ('arjīlah) is the name most commonly used in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Jordan, Uzbekistan, Kuwait and Iraq, while nargilah (Hebrew: נַרְגִּילָה, Arabic: نارجيلة) is the name most commonly used in Israel. It derives from nārgil (Persian: نارگیل), which in turn comes from the Sanskrit word nārikela (नारिकेल), meaning coconut, suggesting that early hookahs were hewn from coconut shells.

In Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Greece, Turkey and Bulgaria, nagile (нагиле) or nagila (нагила) is used to refer to the pipe, while šiša (шиша) refers to شیشه (šiše) meaning glass bottle in Persian. The pipes there often have one or two mouth pieces. The flavored tobacco, created by marinating cuts of tobacco in a multitude of flavored molasses, is placed above the water and covered by pierced foil with hot coals placed on top, and the smoke is drawn through cold water to cool and filter it. In Albania, the hookah is called "lula" or "lulava". In Romania, it is called narghilea.

"Narguile" is the common word in Spain used to refer to the pipe, although "cachimba" is also used, along with "shisha" by Moroccan immigrants in Spain. The word "narguilé" is used in Portuguese. "Narguilé" is also used in French, along with "chicha".

Arabic شيشة (šīšah), through Ottoman Turkish word شیشه (şîşe), itself a direct loanword from Persian شیشه (šīše) meaning "glass container", is the common term for the hookah in Egypt, Sudan and also other Arab world regions such as Arab Peninsula (including Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, UAE, Yemen and Saudi Arabia), Algeria, Tunisia. It is used also in Morocco, Somalia and Cyprus. In Yemen, the Arabic term مداعة (madā`ah) is also used, but for pipes using pure tobacco.

In Persia, hookah is called "qalyān" (قلیان). Persian qalyan is included in the earliest European compendium on tobacco, the tobacologia written by Johan Neander and published in Dutch in 1622. It seems that over time water pipes acquired a Persian connotation as in eighteenth-century Egypt the most fashionable pipes were called Karim Khan after the Persian ruler of the day. This is also the name used in Azerbaijan, Ukraine, Russia, Lithuania and Belarus.

In Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, a hookah is called chillim.

In Kashmiri, hookah is called "Jajeer".

In Maldives, hookah is called "Guduguda".

In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, hookah is called "Shisha".

In the Philippines, hookah is called "hitboo" and normally used in smoking flavored marijuana.

In Sindhi, another language of South Asia, it is called huqqo (حُقو / हुक़्क़ो).

In Vietnam, hookah is called hookah shisha (bình shisha) and shisha is called "shisha tobacco" (thuốc shisha).

History

In the Indian city of Fatehpur Sikri, Roman Catholic missionaries of the Society of Jesus arriving from the southern part of the country introduced tobacco to the Mughal emperor Akbar the Great (1542–1605 AD). Louis Rousselet writes that the physician of Akbar, Hakim Aboul Futteh Ghilani, then invented the hookah in India. However, a quatrain of Ahlī Shirazi (d. 1535), a Persian poet, refers to the use of the ḡalyān (Falsafī, II, p. 277; Semsār, 1963, p. 15), thus dating its use at least as early as the time of the Shah Ṭahmāsp I. It seems, therefore, that Abu’l-Fath Gilani should be credited with the introduction of the ḡalyān, already in use in Persia, into India. There is, however, no evidence of the existence of the water pipe until the 1560s. Moreover, tobacco is believed to have arrived in India in the 17th century, until then cannabis was smoked in India, so that suggests another substance was probably smoked in Ahlī Shirazi's quatrain, perhaps through some other method.

Following the European introduction of tobacco to Persia and India, Hakim Abu’l-Fath Gilani, who came from Gilan, a province in the north of Persia, migrated to Hamarastan. He later became a physician in the Mughal court and raised health concerns after smoking tobacco became popular among Indian noblemen. He subsequently envisaged a system that allowed smoke to be passed through water in order to be 'purified'. Gilani introduced the ḡalyān after Asad Beg, the ambassador of Bijapur, encouraged Akbar I to take up smoking. Following popularity among noblemen, this new device for smoking soon became a status symbol for the Indian aristocracy and gentry.

Modern development

Instead of copper, brass and low-quality alloys, manufacturers increasingly use stainless steel and aluminium. Silicone rubber compounds are used for hookah hoses instead of leather and wire. New materials make modern hookahs more durable, eliminate odors while smoking and allow washing without risks of corrosion or bacterial decay. New technologies and modern design trends are changing the appearance of hookahs. Despite the obvious benefits of modern hookahs, because of high production cost and lack of modern equipment in traditional hookah manufacturing regions, most hookahs are still produced with older technologies.

Culture

South Asia

India

The intricate work on a Malabar hookah.

The intricate work on a Malabar hookah. Gaddi village men with hookah, on mountain path near Dharamshala, India.

Gaddi village men with hookah, on mountain path near Dharamshala, India.

The concept of hookah is thought to have originated in medieval India. Once the province of the wealthy, it was tremendously popular especially during Mughal rule. The hookah has since become less popular; however, it is once again garnering the attention of the masses, and cafés and restaurants that offer it as a consumable are popular. The use of hookahs from ancient times in India was not only a custom, but a matter of prestige. Rich and landed classes would smoke hookahs.

Tobacco is smoked in hookahs in many villages as per traditional customs. Smoking tobacco-molasses is now becoming popular among the youth in India. There are several chain clubs, bars and coffee shops in India offering a wider variety of mu‘assels, including non-tobacco versions. In 2011, hookah was banned in Bangalore. However, it can be bought or rented for personal usage or organized parties.

Koyilandy, a small fishing town on the west coast of India, once made and exported hookahs extensively. These are known as Malabar Hookhas or Koyilandy Hookahs. Today these intricate hookahs are difficult to find outside Koyilandy and are becoming difficult even to find in Koyilandy itself.

As hookah resurges in India, there have been numerous raids and bans recently on hookah smoking, especially in Gujarat.

Pakistan

Although it has been traditionally prevalent in rural areas for generations, smoking hookahs has become very popular in the cosmopolitan cities of Pakistan. One can see many cafés in Pakistan offering hookah smoking to its guests. Many households even have hookahs for smoking or decoration purposes.

In Punjab, Pakhtunkhwa, and in northern Balochistan, the topmost part on which coals are placed is called chillum.

In big cities like Karachi and Lahore, cafes and restaurants offered Hookah and charged per hour. In 2013, it was banned by the Pakistan Supreme court. The cafe owners started offering shisha to minors, which was the major reason for the ban.

Bangladesh

I'tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim from the 18th century, smoking hukka.

I'tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim from the 18th century, smoking hukka. Garo woman smoking a traditional bamboo hookah.

Garo woman smoking a traditional bamboo hookah.

The hookah (Bengali: হুক্কা, romanized: hukka) has been a traditional smoking instrument in Bangladesh, particularly among the old Bengali Muslim zamindar gentry. However, flavoured shisha was introduced in the early 2000s. Hookah lounges spread quite quickly between 2008 and 2011 in urban areas and became popular among young people as well as middle-aged people as a relaxation method. There have been allegations of a government crack-down on hookah bars to prevent illicit drug usage. The hookah is also an electoral symbol for a candidate used first in the 1973 Bangladeshi general election. In the biography of Mountstuart Elphinstone, it is mentioned that James Achilles Kirkpatrick had a hookah-bardar (hookah servant/preparer) during his time in the Indian subcontinent. Kirkpatrick's hookah servant is said to have robbed and cheated Kirkpatrick, making his way to England and stylising himself as the Prince of Sylhet. The man was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of George III.

Nepal

A hookah at a restaurant in Nepal.

A hookah at a restaurant in Nepal. A man smoking tobacco in hookah (or hukka) in Darchula, Nepal.

A man smoking tobacco in hookah (or hukka) in Darchula, Nepal.

Hookahs (हुक़्क़ा), especially wooden ones, are popular in Nepal. Use of hookahs has been usually considered to symbolize an elite family status in Nepali history.

Nowadays, the cities of Kathmandu, Pokhara and Dharan have special hookah bars. Although hookahs have started becoming popular among younger people and tourists, the overall number of hookah smokers is likely dwindling owing to the widespread availability of cheaper cigarettes.

Middle East

In the Arab world and the Middle East, people smoke waterpipes as part of their culture and traditions. Local names of waterpipe in the Middle East are, argila, čelam/čelīm, ḡalyān or ghalyan, ḥoqqa, nafas, nargile, and shisha.

Social smoking is done with a single or double hose hookah, and sometimes even triple or quadruple hose hookahs are used at parties or small get-togethers. When the smoker is finished, they either place the hose back on the table, signifying that it is available, or hand it from one user to the next, folded back on itself so that the mouthpiece is not pointing at the recipient.

Most cafés in the Middle East offer shishas. Cafés are widespread and are among the chief social gathering places in the Arab world (akin to public houses in Britain).

Gaza

In 2010 the Hamas-led Islamist government of Gaza imposed a ban on women smoking hookahs in public. A spokesman for the Interior Ministry explained that "It is inappropriate for a woman to sit cross-legged and smoke in public. It harms the image of our people." The ban was soon lifted later that year and women returned to smoking in popular venues like the cafe of Gaza's Crazy Water Park.

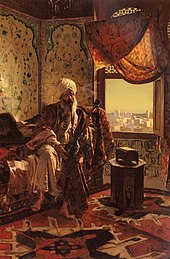

Iran

The exact date of the first use of ḡalyān in Iran is not known. However, the earliest known literary evidence of the hookah, anywhere, comes in a quatrain by Ahlī Shirazi (d. 1535), a Persian poet, referring to the use of the ḡalyān, thus dating its use at least as early as the time of the Shah Ṭahmāsp I. This suggests, the hookah was already in use in ancient Persia, and it made its way into India soon afterward.

Although the Safavid Shah ʿAbbās I strongly condemned tobacco use, towards the end of his reign smoking ḡalyān and čopoq had become common on every level of the society, women included. In schools, both teachers and students had ḡalyāns while lessons continued. Shah Safi of Persia (r. 1629–42) declared a complete ban on tobacco, but the income received from its use persuaded him to soon revoke the ban. The use of ḡalyāns became so widespread that a group of poor people became professional tinkers of crystal water pipes. During the time of Abbas II of Persia (r. 1642–1666), use of the water pipe had become a national addiction. The shah (king) had his own private ḡalyān servants. Evidently the position of water pipe tender (ḡalyāndār) dates from this time. Also at this time, reservoirs were made of glass, pottery, or a type of gourd. Because of the unsatisfactory quality of indigenous glass, glass reservoirs were sometimes imported from Venice. In the time of Suleiman I of Persia (r. 1694–1722), ḡalyāns became more elaborately embellished as their use increased. The wealthy owned gold and silver pipes. The masses spent more on ḡalyāns than they did on the necessities of life.

An emissary of Sultan Husayn (r. 1722–32) to the court of Louis XV of France, on his way to the royal audience at Versailles, had in his retinue an officer holding his ḡalyān, which he used while his carriage was in motion. We have no record indicating the use of ḡalyān at the court of Nader Shah, although its use seems to have continued uninterrupted. There are portraits of Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty of Iran and Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar that depict them smoking the ḡalyān. Iranians have a special tobacco called Khansar (خانسار, presumably name of the origin city, Khvansar). The charcoals would be put on the Khansar without foil.

The Iranian Shia marja' Mirza Shirazi issued his historical fatwa: "In the name of God, the Merciful, the Beneficent. Today the use of both varieties of tobacco, in whatever fashion is reckoned war against the Imam of the Age – may God hasten his advent." The fatwa sparked a huge movement to the extent that even in the private quarters of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1848–1896), hookahs were broken.

Saudi Arabia

In 2014, Saudi Arabia was in the process of implementing general smoking bans in public places. This included shishas. Currently, hookah remains legal in the country, with some restaurants charging customers extra fees.

Syria

Although perceived to be an important cultural feature of Syria (see Smoking in Syria), narghile had declined in popularity during most of the twentieth century and was used mostly by older men. Similar to other Middle Eastern countries, its use increased dramatically during the 1990s, particularly among youth and young adults. As of 2004, prior to the Syrian civil war, 17% of 18- to 29-year-olds, 10% of 30- to 45-year-olds, and 6% of 46- to 65-year-olds reported using narghile, and use was higher in men than women. More recent data is not available.

Turkey and the Balkans

Nargile became part of Turkish and Balkan culture from the 17th century. Back then, it became prominent in society and was used as a status symbol. Nargile was such an important Turkish custom that it even sparked a diplomatic crisis between France and the Ottoman Empire. Western Turkey is noted for its traditional pottery production where potters make earthenware objects, including nargile bowls.

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, the hookah, where it is predominantly called shisha, was particularly used within the Arab and Indian communities.

Hookah was virtually unknown in Southeast Asia before the latter 20th century, yet the popularity among contemporary younger people is now vastly growing. Southeast Asia's most cosmopolitan cities, Makati, Bangkok, Singapore (now banned), Phnom Penh, Siem Reap, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, now have various bars and clubs that offer hookahs to patrons.

Although hookah use has been common for hundreds of years and enjoyed by people of all ages, it has recently started to become a youth pastime in Asia. Hookahs are most popular with college students, and young adults, who may be underage and thus unable to purchase cigarettes.

Kenya

The hookah is called shisha in Kenya. They are officially banned in the country. Despite this, many clubs still continue to defy the law and hookah smoking goes on in urban areas.

South Africa

In South Africa, hookah, colloquially known as a hubbly bubbly or an okka pipe, is popular among the Cape Malay and Indian populations, wherein it is smoked as a social pastime. However, hookah is seeing increasing popularity with South Africans, especially the youth. Bars that additionally provide hookahs are becoming more prominent, although smoking is normally done at home or in public spaces such as beaches and picnic sites.

In South Africa, the terminology of the various hookah components also differ from other countries. The clay "head/bowl" is known as a "clay pot". The hoses are called "pipes" and the air release valve is known as a "clutch".

The windcover (which is considered optional for outside use) is known as an "As-jas", which directly translates from Afrikaans to English as an "ash-jacket". Also, making/preparing the "clay pot" is commonly referred to as "racking the hubbly".

Some scientists point to the marijuana pipe as an African origin of hookah.

United States and Canada

See also: Hookah lounge

During the 1960s and 1970s, hookahs were a popular tool for the consumption of various derivations of tobacco, among other things. At parties or small gatherings the hookah hose was passed around with users partaking as they saw fit. Typically, though, open flames were used instead of burning coals.

Today, hookahs are readily available for sale at smoke shops and some gas stations across the United States, along with a variety of tobacco brands and accessories. In addition to private hookah smoking, hookah lounges or bars have opened in cities across the country.

Recently, certain cities, counties, and states have implemented indoor smoking bans. In some jurisdictions, hookah businesses can be exempted from the policies through special permits. Some permits, however, have requirements such as the business earning a certain minimum percentage of their revenue from alcohol or tobacco.

In cities with indoor smoking bans, hookah bars have been forced to close or switch to tobacco-free mixtures. In many cities, though, hookah lounges have been growing in popularity. From the year 2000 to 2004, over 200 new hookah cafés opened for business, most of them targeted at young adults and located near college campuses or cities with large Middle-Eastern communities. This activity continues to gain popularity within the post-secondary student demographic. Hookah use among high school students declined from 9.4% to 3.4% from 2014 to 2019 while cigarette smoking decreased from 9.2% to 5.8% during this same time period, according to the US CDC. According to a 2018 study, 1.1% of students with some college but no degree, an associate degree or an undergraduate degree reported waterpipe or pipe tobacco product use either every day or some days. As of November 2017, at least 2,082 college or university campuses in the U.S. have adopted 100% smokefree campus policies that attempt to eliminate smoking in indoor and outdoor areas across the entire campus, including residences.

In the United States, the prevalence of hookah use has been noted in a 2019 article to be increasing, particularly among certain states with larger populations of Arab Americans. The use of hookah is more common in urban areas compared to rural areas, and this trend is influenced by factors like availability in public spaces such as cafés and restaurants, as well as cultural and social influences.

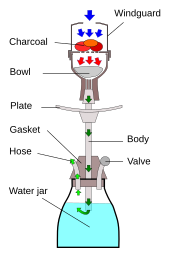

Operation

The jar at the bottom of the hookah is filled with water sufficient to submerge a few centimeters (an inch or two) of the body tube, which is sealed tightly to it. Deeper water will only increase the inhalation force needed to use it. Tobacco or tobacco-free molasses are placed inside the bowl at the top of the hookah. Often the bowl is covered with perforated tin foil or a metal screen and coal placed on top. The foil or screen separates the coal and the tobacco, with the foil and the tobacco reaching maximum temperatures of 450 and 130 degrees Celsius (850 °F and 270 °F) respectively. These temperatures are too low to sustain combustion and considerably lower than the 900 degrees Celsius (1700 °F) found in cigarettes. A larger fraction of the smoke condensates of the hookah are produced by simple distillation rather than by pyrolysis and combustion, and as a result, would tend to carry considerably less of the pyrosynthesized compounds found in cigarette smoke.

As a result of suction through the hose, a vacuum is created in the headspace of the water bowl sufficient to overcome the small static head of the water above the inlet pipe, causing the smoke to bubble into the bowl. At the same time, air is drawn over and heated by the coals. It then passes through the tobacco mixture where due to hot air convection and thermal conduction from the coal, the mainstream aerosol is produced. The vapor is passed down through the body tube that extends into the water in the jar. It bubbles up through the water, losing heat, and fills the top part of the jar, to which the hose is attached. When a user inhales from the hose, smoke passes into the lungs, and the change in pressure in the jar pulls more air through the charcoal, continuing the process. Vapour that has collected in the bowl above the waterline may be exhausted through a purge valve, if present. This one-way valve is opened by the positive pressure created from gently blowing into the hose.

Health effects

Further information: Health effects of tobacco and Mu‘assel § Health effectsExposure to toxic chemicals

Tobacco smoke contains toxic chemicals, including carcinogens (chemicals that cause cancer). Water does not filter out many of these chemicals. The toxic chemicals come from the burning of the charcoal, tobacco, and flavorings. These chemicals can lead to cancer, heart disease, lung disease, and other health problems. The toxic chemicals include tobacco-specific nitrosamines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs; e.g., benzopyrene and anthracene), volatile aldehydes (e.g. formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein), benzene, nitric oxide, heavy metals (arsenic, chromium, lead), and carbon monoxide (CO). Hookah smoking also increases the amount of carbon monoxide (CO) in a person's body to eight times their normal level. Compared to smoking one cigarette, a single hookah session exposes users to more carbon monoxide and PAHs, similar levels of nicotine, and lower levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines. By inhaling these chemicals, hookah smokers are at increased risk of many of the same health problems as cigarette smokers. An average hookah smoking session smokers inhale 100–200 times more smoke inhaled smoking a single cigarette.

Exposure to pathogens that cause infectious diseases

When people share a hookah, there is a risk of spreading infectious diseases such as oral herpes, tuberculosis, hepatitis, influenza, and H. pylori. Using personal disposable mouthpieces may reduce this risk, but does not eliminate it.

Addiction to and dependence on hookah

Hookah smokers inhale nicotine, which is an addictive chemical. A typical hookah smoking session delivers 1.7 times the nicotine dose of one cigarette and the nicotine absorption rate in daily waterpipe users is equivalent to smoking 10 cigarettes per day. Many hookah smokers, especially frequent users, have urges to smoke and show other withdrawal symptoms after not smoking for some time, and it can be difficult to quit. People who become addicted to hookah may be more likely to smoke alone. Hookah smokers who are addicted may find it easier to quit if they have help from a quit-smoking counseling program.

Short-term health effects

Carbon monoxide (CO) in hookah smoke binds to hemoglobin in the blood to form carboxyhemoglobin, which reduces the amount of oxygen that can be transported to organs including the brain. There are several case reports in the medical literature of hookah smokers needing treatment in hospital emergency rooms for symptoms of CO poisoning including headache, nausea, lethargy, and fainting. This is sometimes called "hookah sickness". Hookah smoking can damage the cardiovascular system in several ways. Its use elevates heart rate and blood pressure. It also impairs baroreflex control (which helps to control blood pressure) and cardiac autonomic functioning (which has many purposes, including control of heart rate) Hookah use also acutely harms vascular functioning, increases inflammation, and harms lung function and reduces the ability to exercise.

Long-term health effects

Current evidence indicates hookah causes numerous health problems. Hookah smoking is associated with increased risk of several cancers (lung, esophageal, and gastric), pulmonary diseases (impaired pulmonary function, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema), coronary artery disease, periodontal disease, obstetrical and perinatal problems (low birth weight and pulmonary problems at birth), larynx and voice changes, and osteoporosis. Many of the studies to date have methodological limitations, such as not measuring hookah use in a standardized way. Larger, longitudinal studies are needed to learn more about the long-term health effects of hookah use and of exposure to hookah smoke. Oral health is also affected, notably dental and periodontal status.

Effects of secondhand exposure to hookah smoke

Secondhand smoke from hookahs contains significant amounts of carbon monoxide, aldehydes, PAHs, ultrafine particles, and respirable particulate matter (particles small enough to enter the lungs). Studies have found that concentrations of particulate matter in the air of hookah bars were in the unhealthy to hazardous range according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards. The air in hookah bars also contains significant amounts of toxic chemicals, including aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, nicotine, and trace metals. The concentrations in the air of all these toxic substances are greater than for cigarettes (for the same number of smokers per hour). During a typical one-hour hookah session, a user expels into the air 2-10 times the amount of cancer-causing chemicals and other harmful chemicals compared to a cigarette smoker. No studies have examined the long-term health effects of exposure to secondhand hookah smoke, but short term effects may include experience respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, nasal congestion, and chronic cough.

See also

- Bong

- Chillum (pipe)

- Electronic hookah

- Health effects of tobacco

- Incense

- One-hitter (smoking)

- Pipe smoking

- Thuoc lao

References

- ^ The Ceylon Antiquary and Literary Register, Volume 1. 1916. p. 111.

It has even drawn largely on English, and such words as daktar and platfarm, isteshan and tikat, trem-ghari and rel-ghari, registran karna and apil karna are as common as similar words are in Ceylon. To make up for it Hindustani has not only enriched the vocabulary of Anglo-Indian English with such words as topi and pugre, oheerot and hookah, dhoby and sepoy, ghary and tamasha, durbar and bukshish, Kachcheri and Punkah, but has contributed to it words like jungle, bazar, loot.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Pathak, R. S. (1994). Indianisation of English Language and Literature. Bahri Publications. p. 72.

Bhabani Bhattacharya, who uses Hindi words like taveez, laddoo, hookah, vaid and halwai, also makes deft employment of reverential term Bai for the heroine besides using exclamatory terms as Ho, Han (yes) and Ram-Ram.

- ^ Qasim, Hanan; Alarabi, A. B.; Alzoubi, K. H.; Karim, Z. A.; Alshbool, F. Z.; Khasawneh, F. T. (September 2019). "The effects of hookah/waterpipe smoking on general health and the cardiovascular system" (PDF). Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 24 (58). BioMed Central: 58. Bibcode:2019EHPM...24...58Q. doi:10.1186/s12199-019-0811-y. ISSN 1347-4715. PMC 6745078. PMID 31521105. S2CID 202570973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- Devichand, Mukul (25 June 2007). "UK | Magazine | Pipe dream". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

Despite being a recent addition to British culture, shisha has a long history. Many believe that it originated in India (known there as "hookah") about a thousand years ago, when more often the shisha pipe was used to smoke opium rather than tobacco.

- The cyclopaedia of India and of Jordan and eastern and southern Asia, Volume 2. Bernard Quaritch. 1885. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

HOOKAH. Hindi. The Indian pipe and apparatus for smoking.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hookah" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 670.

- "WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (TobReg) an advisory note Waterpipe tobacco smoking: dangerous health effects include risk to public safety if used by multiple users, research needs and recommended actions by regulators, 2005" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Alarabi, A. B.; Karim, Z. A.; Alshbool, F. Z.; Khasawneh, F. T.; Hernandez, Keziah R.; Lozano, Patricia A.; Montes Ramirez, Jean E.; Rivera, José O. (February 2020). "Short-Term Exposure to Waterpipe/Hookah Smoke Triggers a Hyperactive Platelet Activation State and Increases the Risk of Thrombogenesis". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 40 (2). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 335–349. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313435. ISSN 1079-5642. PMC 7000176. PMID 31941383. S2CID 210335103.

- ^ Patel, Mit P.; Khangoora, Vikramjit S.; Marik, Paul E. (October 2019). "A Review of the Pulmonary and Health Impacts of Hookah Use". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 16 (10). American Thoracic Society: 1215–1219. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201902-129CME. ISSN 2325-6621. PMID 31091965. S2CID 155103502.

- ^ Etemadi, Arash; Blount, Benjamin C.; Calafat, Antonia M.; Chang, Cindy M.; De Jesus, Victor R.; Poustchi, Hossein; Wang, Lanqing; Pourshams, Akram; Shakeri, Ramin; Shiels, Meredith S.; Inoue-Choi, Maki; Ambrose, Bridget K.; Christensen, Carol H.; Wang, Baoguang; Ye, Xiaoyun; Murphy, Gwen; Feng, Jun; Xia, Baoyun; Sosnoff, Connie S.; Boffetta, Paolo; Brennan, Paul; Bhandari, Deepak; Kamangar, Farin; Dawsey, Sanford M.; Abnet, Christian C.; Freedman, Neal D.; Malekzadeh, Reza (February 2019). "Urinary Biomarkers of Carcinogenic Exposure among Cigarette, Waterpipe, and Smokeless Tobacco Users and Never Users of Tobacco in the Golestan Cohort Study". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 28 (2). American Association for Cancer Research: 337–347. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0743. eISSN 1538-7755. ISSN 1055-9965. PMC 6935158. PMID 30622099. S2CID 58560832.

- ^ WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation (2015). Advisory note: waterpipe tobacco smoking: health effects, research needs and recommended actions by regulator (PDF) (2nd. ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- Akl, EA; Gaddam, S; Gunukula, SK; Honeine, R; Jaoude, PA; Irani, J (June 2010). "The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review". International Journal of Epidemiology. 39 (3): 834–57. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq002. ISSN 0300-5771. PMID 20207606.

- ^ El-Zaatari, ZM; Chami, HA; Zaatari, GS (March 2015). "Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking". Tobacco Control. 24 (Suppl 1): i31 – i43. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051908. PMC 4345795. PMID 25661414.

- ^ Sivaramakrishnan, V. M (2001). Tobacco and Areca Nut. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-81-250-2013-4.

The hookah is of historical interest. Portuguese merchants introduced tobacco leaves and European style pipes into Bijapur, the glittering capital of the Adil Shahi kingdom. From here, Asad Beg, the Moghul ambassador in Bijapur, took a large quantity of tobacco leaves and pipes to the Mughal court. He presented Emperor Akbar with some tobacco leaves and a jewel-encrusted European style pope. Out of courtesy and curiosity, Akbar took a few puffs, but his personal physician was worried that tobacco smoke, a hitherto totally unknown substance, might be dangerous. So, he suggested that the smoke be purified by passing it through water, before being inhaled. Thus, the hookah, or water pipe, came into being.

- ^ The Wealth of India. Council of Scientific & Industrial Research. 1976. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

The smoking of hookah and hubble-bubble started in India during the reign of the great Moghul emperor, Akbar

- ^ Khaled Aljarrah; Zaid Q Ababneh; Wael K Al-Delaimy (2009). "Perceptions of hookah smoking harmfulness: predictors and characteristics among current hookah users". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 5 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-5-16. ISSN 1617-9625. PMC 2806861. PMID 20021672.

Hookahs originated in India in the 15th century and then spread to the Near East countries. Hookahs spread first to Persia and underwent further changes to its original shape to the current known shape. In the middle of the 16th century, hookahs reached the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and other Mediterranean regions.

- "ḠALYĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

It seems, therfore, [sic] that Abu'l-Fatḥ Gīlānī should be credited with the introduction of the ḡalyān, already in use in Persia, to India.

- Nichola Fletcher (1 August 2005). Charlemagne's tablecloth: a piquant history of feasting. Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 9780312340681.

- Sandra Alters; Wendy Schiff (28 January 2011). Essential Concepts for Healthy Living Update. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763789756.

- Prakash C. Gupta (1992). Control of tobacco-related cancers and other diseases: proceedings of an international symposium, January 15–19, 1990, TIFR, Bombay. Prakash C. Gupta. p. 33. ISBN 9780195629613.

- Chopra, H. K.; Nanda, Navin C. (30 December 2012). Textbook of Cardiology (A Clinical & Historical Perspective). JP Medical Ltd. ISBN 978-93-5090-081-9.

- Qasim H, Alarabi AB, Alzoubi KH, Karim ZA, Alshbool FZ, Khasawneh FT (September 2019). "The effects of hookah/waterpipe smoking on general health and the cardiovascular system". Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 24 (1): 58. Bibcode:2019EHPM...24...58Q. doi:10.1186/s12199-019-0811-y. PMC 6745078. PMID 31521105.

- Qadeer, Atlaf (2011). "The Socio-Cognitive Dynamics of Hindi/Urdu Lexemes in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Pathak, R. S. (1994). Indianisation of English Language and Literature. Bahri Publications/. p. 24.

In the domain of philosophy, religion and fine arts, particularly music, the words come entirely from Hindi-Sanskrit. The commonest ones are puja, bhajan, shastra, purana, karma, vina, raga, etc. Finally, common festivals and socio-cultural institutions throughout the country provide such terms as Holi, Dee(pa)wali, brahmin, sudra, hookah, bidi, budmash, shikari and so on.

- Steingass, Francis Joseph (1884). The Student's Arabic–English Dictionary. London: W. H. Allen. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- Brockman, LN; Pumper, MA; Christakis, DA; Moreno, MA (December 2012). "Hookah's new popularity among US college students: a pilot study of the characteristics of hookah smokers and their Facebook displays". BMJ Open. 2. 2 (6): e001709. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001709. PMC 3533013. PMID 23242241.

- Dora-Laskey, Prathim-Maya. Postmodern Chic and Postcolonial Cheek: A Map of Linguistic Resistance, Hybridity, and Pedagogy in Rushdie's Midnight's Children. York University. pp. 190–193.

- Cook, Vivian (9 December 2010). It's All in a Word: History, meaning and the Sheer Joy of Words. Profile Books. p. 72. ISBN 9781847653192.

Ever since the British went to India, many words from Indian languages have travelled in the reverse direction. The changing historical relationship between the two countries is shown in the different kinds of words that the English language borrowed at different periods, according to the Indian expert Subba Roa. In the seventeenth century, it was trade that counted. The names of Indian places were used for particular materials, such as calico (a city) or cashere (Kashmir). In the eighteenth century, though trade continued to bring in words such as jute and seersucker, influences came from Indian culture, such as hookah (alias hubble-bubble, a kind of smoking device), and the military, as in sepoy (native Indian soldier).

- Memoirs of William Hickey (Volume II ed.). London: Hurst & Blackett. 1918. p. 136.

- Team, Forvo. "أرجيلة pronunciation: How to pronounce أرجيلة in Arabic". Forvo.com.

- "Nargile". mymerhaba. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- "Smoke like an Egyptian—Sri Lanka". Lankanewspapers.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Nargile on the map". ezglot. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- "Diccionario de la lengua española – Vigésima segunda edición" (in Spanish). Buscon.rae.es. Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Diccionario de la lengua española – Vigésima segunda edición" (in Spanish). Buscon.rae.es. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "تعريف و معنى شيشة في معجم المعاني الجامع". المعاني – معجم عربي عربي. Almaany. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Rudolph P. Matthee (2005). The pursuit of pleasure: drugs and stimulants in Persian history, 1500-1900. Princeton University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0691118550.

- "hookah". Reverso Dictionary. Reverso-Softissimo. 2017. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Robert Connell Clarke (1998). Hashish!. Red Eye Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780929349053.

- "My Teachers And Jajjeer". Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Melvin Ember, Carol R. Ember (2001). Countries and Their Cultures: Laos to Rwanda. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 1377. ISBN 9780028649498.

- "Duden: Shisha". Duden (in German). Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- John Adrian Rosit (1969). Adrian Rosit's Guide to THC. Rex Bookstore. p. 33.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- "Hút shisha hay thuốc lá để đảm bảo sức khỏe". Binhshishagiare.com (in Vietnamese). 12 November 2018. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Rousselet, Louis (2005) . "XXVII — The Ruins of Futtehpore". India and Its Native Princes: Travels in Central India and in the Presidencies of Bombay and Bengal (Reprint — Asian Educational Services 2005 ed.). London: Chapman and Hall. p. 290. ISBN 978-81-206-1887-9.

According to tradition, it was here that he received the Jesuits of Goa, who brought him the leaves and seeds of tobacco and it was a Futtehpore that Hakim Aboul Futteh Ghilani, one of Akbar's physicians, is supposed to have invented the hookah, the pipe of India.

- Blechynden, Kathleen (1905). Calcutta, Past and Present. Los Angeles: University of California. p. 215.

It is said that it was in the early years of their settlement at Hughly that the Portuguese introduced tobacco to the notice of the Emperor Akbar, and that the Indian pipe, the hookah, was invented.

- ^ Rousselet, Louis (1875). India and Its Native Princes: Travels in Central India and in the Presidencies of Bombay and Bengal. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 290. ISBN 9788120618879.

According to tradition, it was here that he received the Jesuits of Goa, who brought him the leaves and seeds of tobacco; and it was at Futtehpore that Hakim Aboul Futteh Ghilani, one of Akbar's physicians, is supposed to have invented the hookah, the pipe of India.

- ^ Razpush, Shahnaz (15 December 2000). "ḠALYĀN". Encyclopedia Iranica. pp. 261–65. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "Tobacco". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Iranica online. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- "An Oriental Delight". What I learned today. Medium. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "Business at hookah-less cafes go up in smoke". The Times of India. 7 June 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013.

- "Hookah". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- Sajid, Khan; Chaouachi, Kamal; Mahmood, Rubaida (2008). "Full text | Hookah smoking and cancer: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels in exclusive/ever hookah smokers". Harm Reduction Journal. 5: 19. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-5-19. PMC 2438352. PMID 18501010.

- "Sheesha ban smoked". The Pakistan Today. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Kaneta Choudhury; S.M.A. Hanifi; Abbas Bhuiya; Shehrin Shaila Mahmood (December 2007). "Sociodemographic Characteristics of Tobacco Consumers in a Rural Area of Bangladesh". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 25 (4): 456–464. PMC 2754020. PMID 18402189.

- Ahmed Shatil Alam. "Killer in disguise". The New Age. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- "Elections symbols prescribed". Bangladesh: a fortnightly news bulletin. Vol. 3. Embassy of Bangladesh. 26 January 1973. p. 4.

- Colebrooke, Thomas Edward (1884). "First Start in Diplomacy". Life of the Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9781108097222. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Dikshit, K. R.; Dikshit, Jutta K. (21 October 2013). North-East India: Land, People and Economy. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789400770553. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Nepal, ECS. "Smoke on The Water: Hubby-bubbly .Hookah". ECS Nepal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- Shane Christensen (25 January 2011). Frommer's Dubai. John Wiley & Sons. p. 141. ISBN 9781119994275. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Fritz Allhoff (23 February 2011). Coffee – Philosophy for Everyone: Grounds for Debate. John Wiley & Sons. p. 10. ISBN 9781444393361. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Gaza ban on women smoking pipes Archived 11 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 19 July 2010, The Independent.

- "Edict lifted for female smokers" Archived 6 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine Jason Koutsoukis, 29 July 2010, The Sunday Morning Herald.

- Falsafī, II, p. 277; Semsār, 1963, p. 15

- Falsafī, II, pp. 278–80

- Rudolph P. Matthee (2005). The pursuit of pleasure: drugs and stimulants in Iranian history, 1500-1900. Princeton University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0691118550. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Chardin, tr., II, p. 899

- Chardin, tr., II, p. 892

- Tavernier apud Semsār, 1963, p. 16

- Herbette, tr. p. 7; Kasrawī, pp. 211–12; Semsār, 1963, pp. 18–19

- "Encyclopædia Iranica | Articles". Iranica.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- https://shiawaves.com/english/uncategorized/98385-jumadi-al-awal-1st-marks-anniversary-of-mirza-shirazis-historic-fatwa-to-ban-tobacco-during-qajar-era/

- "Saudi Arabia bans smoking in public places". The National (Abu Dhabi). 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- "Saudi Arabia Bans Smoking in Most Public Places". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- "New Saudi rules on hookah leave businesses, consumers confused". Arab News. 15 October 2019. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- Rastram, S; Ward, KD; Eissenberg, T; Maziak, W (2004). "Estimating the beginning of the waterpipe epidemic in Syria". BMC Public Health. 4 (32): 32. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-4-32. PMC 514554. PMID 15294023.

- ^ Ward, KD; Hammal, F; Vander Weg, MW; Maziak, W; Eissenberg, T (2006). "The tobacco epidemic in Syria". Tobacco Control. 15 (Supplement 1): i24–9. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.014860. PMC 2563543. PMID 16723671.

- Kinzer, Stephen (10 June 1997). "Inhale the Pleasure of an Unhurried Ottoman Past". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Crane, Howard (1988). "Traditional Pottery Making in the Sardis Region of Western Turkey". Muqarnas. 5: 12.

- Ramachandra SS, Yaldrum A. Shisha smoking: An emerging trend in Southeast Asian nations. J Public Health Policy. 2015 Aug;36(3):304-17.

- "Đánh giá về tác hại của shisha". Gamiecocharm.vn (in Vietnamese). 24 August 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "E-cigarettes, shisha to be illegal from Feb 1 under amended Tobacco Act – CNA". Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- Gundavarapu KC, Dicksit DD, Ramachandra SS. Characteristics of shisha smoking venues in a satellite township near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: an observational study. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation. 2016;2(August):70. doi:10.18332/tpc/64807.

- "Use of Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products Among Students Aged 13-15 Years – Worldwide, 1999-2005". CDC. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- "Nairobians smoking shisha despite ban". Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Has the ban on shisha really worked?". The Star. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Hubble-bubble as cafes go up in smoke". Independent Online. 14 October 2002. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- van der Merwe, N.; et al. (2013). "Hookah pipe smoking among health sciences students". South African Medical Journal. 103 (11): 847–849. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.7448 (inactive 10 November 2024). hdl:11427/34902. PMID 24148170. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - "The Mysterious Origins of the Hookah (Narghile)" The Sacred Narghile Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Jillian Krotki (29 October 2008). "Hookah lounge brings '60s pastime back to the present". Seminole Chronicle. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Harben, Victoria (2 May 2006). "Beyond the Smoke, There is a Solidarity Among Cultures". Cgnews.org. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Lyon, Lindsay "The Hazard in Hookah Smoke". (28 January 2008)

- Quenqua, Douglas (30 May 2011). "Putting a Crimp in the Hookah". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- "Tobacco Product Use Among High School Students" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Arrazola, RA; et al. (17 April 2015). "Tobacco use among middle and high school students--United States, 2011-2014". Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 64 (14): 381–385.

- Wang, TW; Gentzke, AS; Creamer, MR; et al. (6 December 2019). "Tobacco product and associated factors among middle and high school students--United States, 2019". Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 68 (12): 1–22.

- Creamer, MR; Wang, TW; Babb, S; et al. (15 November 2019). "Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults – United States, 2018". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (45): 1013–1019. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2. PMC 6855510. PMID 31725711.

- Wang, TW; Tynan, MA; Hallett, C; et al. (22 June 2018). "Smoke-Free and Tobacco-Free Policies in Colleges and Universities ― United States and Territories, 2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67 (24): 686–689. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6724a4. PMC 6013086. PMID 29927904.

- Qasim, Hanan; Alarabi, Ahmed B.; Alzoubi, Karem H.; Karim, Zubair A.; Alshbool, Fatima Z.; Khasawneh, Fadi T. (14 September 2019). "The effects of hookah/waterpipe smoking on general health and the cardiovascular system". Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 24 (1): 58. Bibcode:2019EHPM...24...58Q. doi:10.1186/s12199-019-0811-y. ISSN 1347-4715. PMC 6745078. PMID 31521105.

- ^ Shihadeh, A (21 July 2002). "Investigation of mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 41 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005. PMID 15388286. S2CID 29182130.

- Wakeham, H (1972). "Recent Trends in Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke Research". The Chemistry of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke. Boston, MA: Springer. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-0462-4_1. ISBN 978-1-4757-0462-4.

- Shihadeh, Alan; Azar, Sima; Antonios, Charbel; Haddad, Antoine; et al. (September 2004). "Towards a Topographical Model of Narghile Water-Pipe café Smoking: A Pilot Study in a High Socioeconomic Status Neighborhood of Beirut, Lebanon". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 79 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005. PMID 15388286. S2CID 29182130.

- ^ Akl, EA; Gaddam, S; Gunukula, SK; Honeine, R; Jaoude, PA; Irani, J (2010). "The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review". International Journal of Epidemiology. 39 (3): 834–57. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq002. PMID 20207606.

- ^ Shihadeh, A; Schubert, J; Klaiany, J; El Sabban, M; Luch, A; Saliba, NA (2015). "Toxicant content, physical properties and biological activity of waterpipe tobacco smoke and its tobacco-free alternatives". Tobacco Control. 24 (Supplement 1): i22 – i30. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051907. PMC 4345918. PMID 25666550.

- Grillo, R; Khemiss, M; Slusarenko da Silva, Y (2023). "Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of waterpipe on oral health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 23 (1): 5–12. doi:10.18295/SQUMJ.6.2022.043. PMC 9974039. PMID 36865434.

- Martinasek, MP; Ward, KD; Calvanese, AV (2014). "Change in carbon monoxide exposure among waterpipe bar patrons". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 16 (7): 1014–9. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu041. PMID 24642592.

- CDCTobaccoFree (20 October 2023). "Hookahs". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- "Hookah Smoking – A Growing Threat to Public Health" (PDF). American Lung Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "Waterpipe and Hookah Smoking – A Dangerous New Trend". Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- Eissenberg, T; Shihadeh, A (December 2009). "Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 37 (6): 518–23. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. PMC 2805076. PMID 19944918.

- Neergaard, J; Singh, P; Job, J; Montgomery, S (October 2007). "Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 9 (10): 987–94. doi:10.1080/14622200701591591. PMC 3276363. PMID 17943617.

- Aboaziza, E; Eissenberg, T (March 2015). "Waterpipe tobacco smoking: what is the evidence that it supports nicotine/tobacco dependence?". Tobacco Control. 24 (Suppl 1): i44 – i53. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051910. PMC 4345797. PMID 25492935.

- ^ Asfar, T; Al Ali, R; Rastam, S; Maziak, W; Ward, KD (June 2014). "Behavioral cessation treatment of waterpipe smoking: The first pilot randomized controlled trial". Addictive Behaviors. 39 (6): 1066–74. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.012. PMC 4141480. PMID 24629480.

- Rastam, S; Eissenberg, T; Ibrahim, I; Ward, KD; Khalil, R; Maziak, W (May 2011). "Comparative analysis of waterpipe and cigarette suppression of abstinence and craving symptoms". Addictive Behaviors. 36 (5): 555–9. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.021. PMC 3061840. PMID 21316156.

- Ward, KD; Hammal, F; VanderWeg, MW; Eissenberg, T; Asfar, T; Rastam, S; Maziak, W (February 2005). "Are waterpipe users interested in quitting?". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 7 (1): 149–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.625.4651. doi:10.1080/14622200412331328402. PMID 15804687.

- Maziak, W; Eissenberg, T; Ward, KD (January 2005). "Patterns of waterpipe use and dependence: implications for intervention development". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 80 (1): 173–9. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.026. PMID 15652393. S2CID 22556876.

- Dogar, O; Jawad, M; Shah, SK; Newell, JN; Kanaan, M; Khan, MA; Siddiqi, K (June 2014). "Effect of cessation interventions on hookah smoking: post-hoc analysis of a cluster-randomized controlled trial". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 16 (6): 682–8. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt211. PMID 24376277.

- Maziak, Wasim; Jawad, Mohammed; Jawad, Sena; Ward, Kenneth D.; Eissenberg, Thomas; Asfar, Taghrid (31 July 2015). "Interventions for waterpipe smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (7): CD005549. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005549.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4838024. PMID 26228266.

- Cavus, UY; Rehber, ZH; Ozeke, O; Ilkay, E (2010). "Carbon monoxide poisoning associated with narghile use". Emergency Medicine Journal. 27 (5): 406. doi:10.1136/emj.2009.077214. PMID 20442182. S2CID 2332261.

- La Fauci, G; Weiser, G; Steiner, IP; Shavit, I (2012). "Carbon monoxide poisoning in narghile (water pipe) tobacco smokers". Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 14 (1): 57–59. doi:10.2310/8000.2011.110431. PMID 22417961.

- Lim, BL; Lim, GH; Seow, E (2009). "Case of carbon monoxide poisoning after smoking shisha". International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2 (2): 121–122. doi:10.1007/s12245-009-0097-8. PMC 2700232. PMID 20157455.

- Türkmen, S; Eryigit, U; Sahin, A; Yeniocak, S; Turedi, S (2011). "Carbon monoxide poisoning associated with water pipe smoking". Clinical Toxicology. 49 (7): 697–698. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.598160. PMID 21819288. S2CID 43906064.

- Pearl, Mike. "Is hookah sickness just carbon monoxide poisoning". Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Alomari, MA; Khabour, OF; Alzoubi, KH; Shqair, DM; Eissenberg, T (2014). "Central and peripheral cardiovascular changes immediately after waterpipe smoking". Inhal Toxicol. 26 (10): 579–587. Bibcode:2014InhTx..26..579A. doi:10.3109/08958378.2014.936572. PMID 25144473. S2CID 30687980. Archived from the original on 26 March 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- Al-Kubati, M; Al-Kubati, AS; al'Absi, M; Fiser, B. (2006). "The short-term effect of water-pipe smoking on the baroreflex control of heart rate in normotensives". Autonomic Neuroscience. 126–127: 146–9. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2006.03.007. PMID 16716761. S2CID 31388586.

- Cobb, CO; Sahmarani, K; Eissenberg, T; Shihadeh, A (2012). "Acute toxicant exposure and cardiac autonomic dysfunction from smoking a single narghile waterpipe with tobacco and with a "healthy" tobacco-free alternative". Toxicology Letters. 215 (1): 70–75. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.09.026. PMC 3641895. PMID 23059956.

- St Helen, G; Benowitz, NL; Dains, KM; Havel, C; Peng, M; Jacob, P (2014). "Nicotine and carcinogen exposure after water pipe smoking in hookah bars". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 23 (6): 1055–66. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0939. PMC 4047652. PMID 24836469.

- Hakim, F; Hellou, E; Goldbart, A; Katz, R; Bentur, Y; Bentur, L (April 2011). "The acute effects of water-pipe smoking on the cardiorespiratory system". Chest. 139 (4): 775–81. doi:10.1378/chest.10-1833. PMID 21030492.

- Hawari, FI; Obeidat, NA; Ayub, H; Ghonimat, I; Eissenberg, T; Dawahrah, S; Beano, H (August 2013). "The acute effects of waterpipe smoking on lung function and exercise capacity in a pilot study of healthy participants". Inhalation Toxicology. 25 (9): 492–7. Bibcode:2013InhTx..25..492H. doi:10.3109/08958378.2013.806613. PMID 23905967. S2CID 22728685.

- CDCTobaccoFree (23 April 2021). "Hookahs". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Grillo, R; Khemiss, M; Bibars, A; Slusarenko da Silva, Y (2023). "Impact of waterpipe smoking on oral health of users: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Prosthodontics. 72 (4): 322–332. doi:10.5114/PS/157370. S2CID 254625804.

- Kumar, SR; Davies, S; Weitzman, M; Sherman, S (March 2015). "A review of air quality, biological indicators and health effects of second-hand waterpipe smoke exposure". Tobacco Control. 24 (Suppl 1): i54 – i59. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052038. PMC 4345792. PMID 25480544.

- ^ Daher, N; Saleh, R; Jaroudi, E; Sheheitli, H; Badr, T; Sepetdjian, E; Al Rashidi, M; Saliba, N; Shihadeh, A (1 January 2010). "Comparison of carcinogen, carbon monoxide, and ultrafine particle emissions from narghile waterpipe and cigarette smoking: Sidestream smoke measurements and assessment of second-hand smoke emission factors". Atmospheric Environment. 44 (1): 8–14. Bibcode:2010AtmEn..44....8D. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.10.004. PMC 2801144. PMID 20161525.

- Tamim, H; Musharrafieh, U; El Roueiheb, Z; Yunis, K; Almawi, WY (2003). "Exposure of children to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and its association with respiratory ailments". The Journal of Asthma. 40 (5): 571–6. doi:10.1081/jas-120019029. PMID 14529107. S2CID 35129626.

- Zeidan, RK; Rachidi, S; Awada, S; El Hajje, A; El Bawab, W; Salamé, J; Bejjany, R; Salameh, P (August 2014). "Carbon monoxide and respiratory symptoms in young adult passive smokers: a pilot study comparing waterpipe to cigarette". International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 27 (4): 571–82. doi:10.2478/s13382-014-0246-z. PMID 25012596.

External links

Media related to Hookahs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hookahs at Wikimedia Commons- WHO Report on water pipe (hookah), by WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation.

- Chaouachi, Kamal (2006). "A critique of the WHO Tob Reg's "Advisory Note" report entitled: "Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Health effects, research needs and recommended actions by regulators"". Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine. 5: 17. doi:10.1186/1477-5751-5-17. PMC 1664583. PMID 17112380.

- Scientific Evidence of the Health Risks of Hookah Smoking Archived 10 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine (University of Maryland, College Park: 9 June 2008, vol 17, issue 23)