The question mark ? (also known as interrogation point, query, or eroteme in journalism) is a punctuation mark that indicates a question or interrogative clause or phrase in many languages.

History

In the fifth century, Syriac Bible manuscripts used question markers, according to a 2011 theory by manuscript specialist Chip Coakley: he believes the zagwa elaya ("upper pair"), a vertical double dot over a word at the start of a sentence, indicates that the sentence is a question.

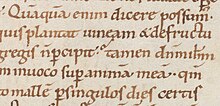

From around 783, in Godescalc Evangelistary, a mark described as "a lightning flash, striking from right to left" is attested. This mark is later called a punctus interrogativus. According to some paleographers, it may have indicated intonation, perhaps associated with early musical notation like neumes. Another theory, is that the "lightning flash" was originally a tilde or titlo, as in ·~, one of many wavy or more or less slanted marks used in medieval texts for denoting things such as abbreviations, which would later become various diacritics or ligatures.

From the 10th century, the pitch-defining element (if it ever existed) seems to have been gradually forgotten, so that the "lightning flash" sign (with the stroke sometimes slightly curved) is often seen indifferently at the end of clauses, whether they embody a question or not.

In the early 13th century, when the growth of communities of scholars (universities) in Paris and other major cities led to an expansion and streamlining of the book-production trade, punctuation was rationalized by assigning the "lightning flash" specifically to interrogatives; by this time the stroke was more sharply curved and can easily be recognized as the modern question mark. (See, for example, De Aetna [it] (1496) printed by Aldo Manuzio in Venice.)

In 1598, the English term point of interrogation is attested in an Italian–English dictionary by John Florio.

In the 1850s, the term question mark is attested:

The mark which you are to notice in this lesson is of this shape ? You see it is made by placing a little crooked mark over a period.... The name of this mark is the Question Mark, because it is always put after a question. Sometimes it is called by a longer and harder name. The long and hard name is the Interrogation Point.

Scope

In English, the question mark typically occurs at the end of a sentence, where it replaces the full stop (period). However, the question mark may also occur at the end of a clause or phrase, where it replaces the comma (see also Question comma):

- "Is it good in form? style? meaning?"

or:

- "Showing off for him, for all of them, not out of hubris—hubris? him? what did he have to be hubrid about?—but from mood and nervousness."

- — Stanley Elkin.

This is quite common in Spanish, where the use of bracketing question marks explicitly indicates the scope of interrogation.

- En el caso de que no puedas ir con ellos, ¿quieres ir con nosotros? ('In case you cannot go with them, would you like to go with us?')

A question mark may also appear immediately after questionable data, such as dates:

- Genghis Khan (1162?–1227)

In other languages and scripts

Opening and closing question marks in Spanish

Main article: Inverted question and exclamation marks

In Spanish, since the second edition of the Ortografía of the Real Academia Española in 1754, interrogatives require both opening ¿ and closing ? question marks. An interrogative sentence, clause, or phrase begins with an inverted question mark ¿ and ends with the question mark ?, as in:

- Ella me pregunta «¿qué hora es?» – 'She asks me, "What time is it?"'

Question marks must always be matched, but to mark uncertainty rather than actual interrogation omitting the opening one is allowed, although discouraged:

- Gengis Khan (¿1162?–1227) is preferred in Spanish over Gengis Khan (1162?–1227)

The omission of the opening mark is common in informal writing, but is considered an error. The one exception is when the question mark is matched with an exclamation mark, as in:

- ¡Quién te has creído que eres? – 'Who do you think you are?!'

(The order may also be reversed, opening with a question mark and closing with an exclamation mark.) Nonetheless, even here the Academia recommends matching punctuation:

- ¡¿Quién te has creído que eres?!

The opening question mark in Unicode is U+00BF ¿ INVERTED QUESTION MARK (¿).

In other languages of Spain

Galician also uses the inverted opening question mark, though usually only in long sentences or in cases that would otherwise be ambiguous. Basque and Catalan, however, use only the terminal question mark.

Solomon Islands Pidgin

In Solomon Islands Pidgin, the question can be between question marks since, in yes/no questions, the intonation can be the only difference.

?Solomon Aelan hemi barava gudfala kandre, ia man? ('Solomon Islands is a great country, isn't it?')

Armenian question mark

|

In Armenian, the question mark is a diacritic that takes the form of an open circle and is placed over the stressed vowel of the question word. It is defined in Unicode at U+055E ◌՞ ARMENIAN QUESTION MARK.

Greek question mark

The Greek question mark (Greek: ερωτηματικό, romanized: erōtīmatikó) looks like ;. It appeared around the same time as the Latin one, in the 8th century. It was adopted by Church Slavonic and eventually settled on a form essentially similar to the Latin semicolon. In Unicode, it is separately encoded as U+037E ; GREEK QUESTION MARK, but the similarity is so great that the code point is normalised to U+003B ; SEMICOLON, making the marks identical in practice.

Mirrored question mark in right-to-left scripts

"؟" redirects here. For the symbol this may also stand for, see Irony punctuation.

In Arabic and other languages that use Arabic script such as Persian, Urdu and Uyghur (Arabic form), which are written from right to left, the question mark is mirrored right-to-left from the Latin question mark. In Unicode, two encodings are available: U+061F ؟ ARABIC QUESTION MARK (With bi-directional code AL: Right-to-Left Arabic) and U+2E2E ⸮ REVERSED QUESTION MARK (With bi-directional code Other Neutrals). Some browsers may display the character in the previous sentence as a forward question mark due to font or text directionality issues. In addition, the Thaana script in Dhivehi uses the mirrored question mark: މަރުހަބާ؟

The Arabic question mark is also used in some other right-to-left scripts: N'Ko, Syriac and Adlam. Adlam also has U+1E95F 𞥟 ADLAM INITIAL QUESTION MARK: 𞥟 𞤢𞤤𞤢𞥄 ؟, 'No?'.

Hebrew script is also written right-to-left, but it uses a question mark that appears on the page in the same orientation as the left-to-right question mark (e.g. את מדברת עברית?).

Fullwidth question mark in East Asian languages

The question mark is also used in modern writing in Chinese and, to a lesser extent, Japanese. Usually, it is written as fullwidth form in Chinese and Japanese, in Unicode: U+FF1F ? FULLWIDTH QUESTION MARK. Fullwidth form is always preferred in official usage. In Korean language, however, halfwidth is used.

Japanese has a spoken indicator of questions, か (ka), which essentially functions as a verbal question mark. Therefore, the question mark is optional with か in Japanese. For example, both 終わったのかもしれませんよ。 or 終わったのかもしれませんよ? are correct to express "It may be over". The question mark is not used in official usages such as governmental documents or school textbooks. Most Japanese people do not use the question mark as well, but the usage is increasing.

Chinese also has a spoken indicator of questions, which is 吗 (ma). However, the question mark should always be used after 吗 when asking questions.

In other scripts

Some other scripts have a specific question mark:

- U+1367 ፧ ETHIOPIC QUESTION MARK

- U+A60F ꘏ VAI QUESTION MARK

- U+2CFA ⳺ COPTIC OLD NUBIAN DIRECT QUESTION MARK, and U+2CFB ⳻ COPTIC OLD NUBIAN INDIRECT QUESTION MARK

- U+1945 ᥅ LIMBU QUESTION MARK

Stylistic variants

French orthography specifies a narrow non-breaking space before the question mark. (e.g., "Que voulez-vous boire ?"); in English orthography, no space appears in front of the question mark (e.g. "What would you like to drink?").

Typological variants of ?

The rhetorical question mark or percontation point (see Irony punctuation) was invented by Henry Denham in the 1580s and was used at the end of a rhetorical question; however, it became obsolete in the 17th century. It was the reverse of an ordinary question mark, so that instead of the main opening pointing back into the sentence, it opened away from it. This character can be represented using U+2E2E ⸮ REVERSED QUESTION MARK.

Bracketed question marks can be used for rhetorical questions, for example Oh, really(?), in informal contexts such as closed captioning.

The question mark can also be used as a meta-sign to signal uncertainty regarding what precedes it. It is usually put between brackets: (?). The uncertainty may concern either a superficial level (such as unsure spelling), or a deeper truth (real meaning).

In typography, some other variants and combinations are available: "⁇," "⁈," and "⁉," are usually used for chess annotation symbols; the interrobang, "‽," is used to combine the functions of the question mark and the exclamation mark, superposing these two marks.

Unicode makes available these variants:

- U+2047 ⁇ DOUBLE QUESTION MARK

- U+2048 ⁈ QUESTION EXCLAMATION MARK

- U+2049 ⁉ EXCLAMATION QUESTION MARK

- ⁉️ with an emoji variation selector

- U+203D ‽ INTERROBANG

- U+2E18 ⸘ INVERTED INTERROBANG

- U+2E2E ⸮ REVERSED QUESTION MARK

- U+061F ؟ ARABIC QUESTION MARK

- U+FE56 ﹖ SMALL QUESTION MARK

- U+00BF ¿ INVERTED QUESTION MARK (¿)

- U+2753 ❓ BLACK QUESTION MARK ORNAMENT

- U+2754 ❔ WHITE QUESTION MARK ORNAMENT

- U+1F679 🙹 HEAVY INTERROBANG ORNAMENT

- U+1F67A 🙺 SANS-SERIF INTERROBANG ORNAMENT

- U+1F67B 🙻 HEAVY SANS-SERIF INTERROBANG ORNAMENT

Computing

In computing, the question mark character is represented by ASCII code 63 (0x3F hexadecimal), and is located at Unicode code-point U+003F ? QUESTION MARK (?). The full-width (double-byte) equivalent (?), is located at code-point U+FF1F ? FULLWIDTH QUESTION MARK.

The inverted question mark (¿) corresponds to Unicode code-point U+00BF ¿ INVERTED QUESTION MARK (¿), and can be accessed from the keyboard in Microsoft Windows on the default US layout by holding down the Alt and typing either 1 6 8 (ANSI) or 0 1 9 1 (Unicode) on the numeric keypad. In GNOME applications on Linux operating systems, it can be entered by typing the hexadecimal Unicode character (minus leading zeros) while holding down both Ctrl and Shift, i.e.: Ctrl Shift B F. In recent XFree86 and X.Org incarnations of the X Window System, it can be accessed as a compose sequence of two straight question marks, i.e. pressing Compose ? ? yields ¿. In classic Mac OS and Mac OS X (macOS), the key combination Option Shift ? produces an inverted question mark.

In shell and scripting languages, the question mark is often utilized as a wildcard character: a symbol that can be used to substitute for any other character or characters in a string. In particular, filename globbing uses "?" as a substitute for any one character, as opposed to the asterisk, "*", which matches zero or more characters in a string.

The question mark is used in ASCII renderings of the International Phonetic Alphabet, such as SAMPA, in place of the glottal stop symbol, ʔ, (which resembles "?" without the dot), and corresponds to Unicode code point U+0294 ʔ LATIN LETTER GLOTTAL STOP.

In computer programming, the symbol "?" has a special meaning in many programming languages. In C-descended languages, ? is part of the ?: operator, which is used to evaluate simple boolean conditions. In C# 2.0, the ? modifier is used to handle nullable data types and ?? is the null coalescing operator. In the POSIX syntax for regular expressions, such as that used in Perl and Python, ? stands for "zero or one instance of the previous subexpression", i.e. an optional element. It can also make a quantifier like {x,y}, + or * match as few characters as possible, making it lazy, e.g. /^.*?px/ will match the substring 165px in 165px 17px instead of matching 165px 17px. In certain implementations of the BASIC programming language, the ? character may be used as a shorthand for the "print" function; in others (notably the BBC BASIC family), ? is used to address a single-byte memory location. In OCaml, the question mark precedes the label for an optional parameter. In Scheme, as a convention, symbol names ending in ? are used for predicates, such as odd?, null?, and eq?. Similarly, in Ruby, method names ending in ? are used for predicates. In Swift a type followed by ? denotes an option type; ? is also used in "optional chaining", where if an option value is nil, it ignores the following operations. Similarly, in Kotlin, a type followed by ? is nullable and functions similar to option chaining are supported. In APL, ? generates random numbers or a random subset of indices. In Rust, a ? suffix on a function or method call indicates error handling. In SPARQL, the question mark is used to introduce variable names, such as ?name. In MUMPS, it is the pattern match operator.

In many Web browsers and other computer programs, when converting text between encodings, it may not be possible to map some characters into the target character set. In this situation it is common to replace each unmappable character with a question mark ?, inverted question mark ¿, or the Unicode replacement character, usually rendered as a white question mark in a black diamond: U+FFFD � REPLACEMENT CHARACTER. This commonly occurs for apostrophes and quotation marks when they are written with software that uses its own proprietary non-standard code for these characters, such as Microsoft Office's "smart quotes".

The generic URL syntax allows for a query string to be appended to a resource location in a Web address so that additional information can be passed to a script; the query mark, ?, is used to indicate the start of a query string. A query string is usually made up of a number of different field/value pairs, each separated by the ampersand symbol, &, as seen in this URL:

http://www.example.com/search.php?query=testing&database=English

Here, a script on the page search.php on the server www.example.com is to provide a response to the query string containing the pairs query=testing and database=English.

Games

In algebraic chess notation, some chess punctuation conventions include: "?" denotes a bad move, "??" a blunder, "?!" a dubious move, and "!?" an interesting move.

In Scrabble, a question mark indicates a blank tile.

Linguistics

In most areas of linguistics, but especially in syntax, a question mark in front of a word, phrase or sentence indicates that the form in question is strongly dispreferred, "questionable" or "strange", but not outright ungrammatical. (The asterisk is used to indicate outright ungrammaticality.)

Other sources go further and use several symbols (e.g. the question mark and the asterisk plus ?* or the degree symbol °) to indicate gradations or a continuum of acceptability.

Yet others use double question marks ?? to indicate a degree of strangeness between those indicated by a single question mark and that indicated by the combination of question mark and asterisk.

Mathematics and formal logic

In mathematics, "?" commonly denotes Minkowski's question mark function.

In linear logic, the question mark denotes one of the exponential modalities that control weakening and contraction.

When placed above the relational symbol in an equation or inequality, a question-mark annotation means that the stated relation is "questioned". This can be used to ask whether the relation might be true or to point out the relation's possible invalidity.

- U+225F ≟ QUESTIONED EQUAL TO

- U+2A7B ⩻ LESS-THAN WITH QUESTION MARK ABOVE

- U+2A7C ⩼ GREATER-THAN WITH QUESTION MARK ABOVE

Medicine

A question mark is used in English medical notes to suggest a possible diagnosis. It facilitates the recording of a doctor's impressions regarding a patient's symptoms and signs. For example, for a patient presenting with left lower abdominal pain, a differential diagnosis might include ?diverticulitis (read as "query diverticulitis").

See also

- Betteridge's law of headlines – Journalistic adage on questions in headlines

- Cosmic "Question Mark"

- High rising terminal – An intonation pattern in some varieties of English ('upspeak', 'uptalk')

- Inquiry – Any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem

- Interrobang – Combined question mark and exclamation mark

- Irony punctuation – Proposed form of notation used to denote irony or sarcasm in text

- List of typographical symbols and punctuation marks

- Terminal punctuation – Marks that identify the end of some text

Notes

- The Perl Compatible Regular Expressions library implements the

Uflag, which reverses behavior of quantifiers: these become lazy by default, and?can make them greedy. - One article notes succinctly that "common practice in linguistics an asterisk preceding a word, a clause or a sentence is used to indicate ungrammaticality or unacceptability, while a question mark is used to indicate questionable usage", another that, "A question mark indicates that the example is marginal; an asterisk indicates unacceptability" and another that "examples preceded by an asterisk are ungrammatical, and those preceded by a question mark would be considered strange".

- One example is "rough approximations of acceptability are given in four gradations and indicated as follows: normal and preferred, no mark; acceptable but not preferred, degree sign

°; marginally acceptable, question mark (?); unacceptable, asterisk (*)."

References

- Truss 2003, p. 139.

- "The riddle of the Syriac double dot: it's the world's earliest question mark". University of Cambridge. 2011-07-21. Archived from the original on 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- "Symbol in Syriac may be world's first question mark". Reuters. 2011-07-21. Archived from the original on 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ "The Grammarphobia Blog: Who invented the question mark?". www.grammarphobia.com. 2022-02-28. Archived from the original on 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- Truss 2003, p. 159.

- Parkes, M. B. (1993). Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07941-8.

- The Straight Dope on the question mark Archived July 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (link down)

- De Hamel, Christopher History of Illuminated Manuscripts, 1997

- Bembo, Pietro (1495–1496). De Aetna. Venice: Aldo Pio Manuzio. f. 4v.

- Florio, John (1598). A worlde of wordes, or, Most copious, and exact dictionarie in Italian and English. London: By Arnold Hatfield for Edw. Blount. p. 188.

Iterogatiuo punto, a point of interrogation.

- Parker, Richard Green; Watson, J. Madison (1859). The National Second Reader: Containing preliminary exercises in articulation, pronunciation, and punctuation. National series; no. 2. New York: A. S. Barnes & Burr. p. 20. hdl:2027/nc01.ark:/13960/t26988j57.

- Elkin, Stanley (1991). The MacGuffin. p. 173.

- Truss 2003, p. 142–143.

- Ortografía de la Lengua Castellana (in Spanish). Madrid: Real Academia Española. 1779 – via Internet Archive.

- Interrogación y exclamación (signos de). Punto 3d.

- Interrogación y exclamación (signos de). Punto 3b.

- Lee, Ernie (1999). Pidgin Phrasebook (2nd ed.). Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0864425872.

- Thompson, Edward Maunde (1912). An Introduction to Greek and Latin Palaiography. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 60 ff. Retrieved December 10, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Nicolas, Nick (November 20, 2014). "Greek Unicode Issues: Punctuation". Thesaurus Linguae Graecae: A Digital Library of Greek Literature. University of California, Irvine. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015.". 2005. Accessed 7 October 2014.

- "Adlam/Pular orthography notes". r12a.github.io. 5 January 2023. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- Truss 2003, p. 143.

- "标点符号用法" (PDF). Chinese Ministry of Education (in Simplified Chinese).

句号、逗号、顿号、分号、冒号均置于相应文字之后,占一个字位置,居左下,不出现在一行之首。

- "常用格式說明" (PDF). Chinese Journal of Psychology (in Traditional Chinese).

請使用新式標準符號,所有的中文標點符號都要佔全形。

- "記述上の約束事". The Japan Sociological Society (in Japanese). 8 February 2019.

和文を書くときには,原則としてすべて全角文字を使用しなければならない.漢字,ひらがな,カタカナのみならず,句読点やカッコ記号なども,全角文字を使用すること(このルールの例外については,そのつど述べる).

- 심우진 (December 2011). "한글 타이포그라피 환경으로서의 문장부호에 대하여 : 표준화 이슈를 중심으로 개선 방향 제안". 글짜씨 (in Korean). 3 (2): 987–1005. ISSN 2093-1166. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

일반적인 키보드 입력 환경에서 사용하는 문장 부호는 대부분 반각 문장 부호이며, 이들은 라틴 문자의 문장 부호를 차용한 것이다.

- 塩田雄大. "疑問文でないのに"?"を付けてもよいか?". NHK放送文化研究所 (in Japanese).

- "标点符号用法" (PDF). Chinese Ministry of Education (in Simplified Chinese).

使用问号主要根据语段前后有较大停顿、带有疑问语气和语调,并不取决于句子的长短。

- "Ponctuation". Lexique des règles typographiques en usage à l'Imprimerie nationale (in French) (3e ed.). Imprimerie nationale. October 2007. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-2-7433-0482-9..

- "Learn English Punctuation - English Punctuation Rules". www.learnenglish.de. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ Truss 2003, p. 142.

- Mandeville, Henry (1851). A Course of Reading for Common Schools and the Lower Classes of Academies. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- "Character Codes – HTML Codes, Hexadecimal Codes & HTML Names". Character-Code.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- "Scrabble Glossary". Tucson Scrabble Club. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- Xu, Hui Ling (2007). "Aspect of Chaozhou Grammar A Synchronic Description of the Jieyang Variety / 潮州話揭陽方言語法研究". Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monograph Series (22): i–xiv, 1–304. ISSN 2409-2878. JSTOR 23826160. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Simons, Mandy (August 1996). "Pronouns and Definite Descriptions: A Critique of Wilson". The Journal of Philosophy. 93 (8): 408–420. doi:10.2307/2941036. JSTOR 2941036. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Everett, Daniel L. (August–October 2005). "Cultural Constraints on Grammar and Cognition in Pirahã: Another Look at the Design Features of Human Language". Current Anthropology. 46 (4): 621–646. doi:10.1086/431525. hdl:2066/41103. JSTOR 10.1086/431525. S2CID 2223235. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Graffi, Giorgio (May 2002). "The Asterisk from Historical to Descriptive and Theoretical Linguistics: An historical note". Historiographia Linguistica. 29 (3): 329–338. doi:10.1075/hl.29.3.04gra. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Timberlake, Alan (Summer 1975). "Hierarchies in the Genitive of Negation". The Slavic and East European Journal. 19 (2): 123–138. doi:10.2307/306765. JSTOR 306765. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Trask, R. L. (1993). A Dictionary of Grammatical Terms in Linguistics. London: Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 0-415-08627-2.

- Jones, Michael Alan (1996). Foundations of French Syntax. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. xxv. ISBN 0-521-38104-5.

Bibliography

- Truss, Lynne (2003). Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. London: Profile Books. ISBN 1861976127.

- Lupton, Ellen; Miller, J. Abbott (2003). "Period Styles: A Punctuated History" (PDF). In Peterson, Linda H. (ed.). The Norton Reader (11th ed.). Norton. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2017 – via Think-gn.com – online excerpt (at least – may be full text of chapter), pp. 3–7.

External links

- "The Question Mark". Guide to Grammar & Writing. Hartford, Connecticut: Capital Community College Foundation. 2004. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2017. – provides an overview of question mark usage, and the differences between direct, indirect, and rhetorical questions.

| Common punctuation and other typographical symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| |