| Revision as of 20:41, 6 June 2007 view source207.229.164.203 (talk) →Description← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:42, 20 December 2024 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,406,324 edits Added newspaper. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 50/662 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Genus of flowering plants}} | |||

| {{wiktionary}}{{Taxobox | |||

| {{About|the plant genus|therapeutic use|Medical cannabis|the psychoactive drug|Cannabis (drug)|other uses|Cannabis (disambiguation)}} | |||

| | color = lightgreen | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| | name = Cannabis | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| {{Automatic taxobox | |||

| | fossil_range = Early ] – Present {{fossilrange|19.6|0}} | |||

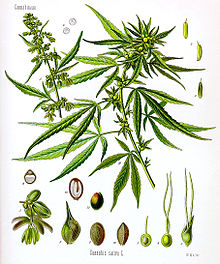

| | image = Cannabis sativa Koehler drawing.jpg | | image = Cannabis sativa Koehler drawing.jpg | ||

| | image_caption = Common hemp | |||

| | image_width = 203px | |||

| | |

| taxon = Cannabis | ||

| | |

| authority = ] | ||

| | classis = ] | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| | genus = '''''Cannabis''''' | |||

| | genus_authority = ] | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Species | | subdivision_ranks = Species | ||

| | subdivision_ref = <ref name="GuyWhittle2004">{{cite book |author-link1 = Geoffrey William Guy |vauthors = Guy GW, Whittle BA, Robson P |title=The Medicinal Uses of Cannabis and Cannabinoids |year=2004 |publisher=Pharmaceutical Press |isbn=978-0-85369-517-2 |pages=74–}}</ref> | |||

| | subdivision = | |||

| | subdivision = * '']'' L. | |||

| ]<br /> | * '']'' Lam. | ||

| ] | * '']'' Janisch | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Cannabis sidebar}} | |||

| '''''Cannabis''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|æ|n|ə|b|ɪ|s}})<ref name="Publishing2010">{{cite book |title=Dictionary of Medical Terms |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uFfl2zc_ivYC&pg=PT139 |year=2010 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-1-4081-3635-5 |page=139 |access-date=28 June 2020 |archive-date=5 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200805204228/https://books.google.com/books?id=uFfl2zc_ivYC&pg=PT139 |url-status=live}}</ref> is a ] of ]s in the family ]. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: '']'', '']'', and '']''. Alternatively, ''C. ruderalis'' may be included within ''C. sativa'', or all three may be treated as ] of ''C. sativa'',<ref name=GuyWhittle2004/><ref>{{cite web |title=Classification Report |url=https://plants.usda.gov/java/ClassificationServlet?classid=CASA3 |publisher=] |access-date=13 February 2017|archive-date=6 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181206102613/https://plants.usda.gov/java/ClassificationServlet?classid=CASA3 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Indica, Sativa, Ruderalis – Did We Get It All Wrong?|url=http://theleafonline.com/c/science/2015/01/indica-sativa-ruderalis-get-wrong/ |website=The Leaf Online|access-date=13 February 2017 |date=26 January 2015|archive-date=14 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170214004241/http://theleafonline.com/c/science/2015/01/indica-sativa-ruderalis-get-wrong/ |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomylist.aspx?category=species&type=genus&value=Cannabis&id=2034 |title=Species of ''Cannabis'' |website=GRIN Taxonomy |access-date=13 February 2017 |archive-date=13 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170213164940/https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomylist.aspx?category=species&type=genus&value=Cannabis&id=2034 |url-status=live }}</ref> or ''C. sativa'' may be accepted as a single undivided species.<ref name="POWO_306087-2">{{cite web |title=''Cannabis sativa'' L. |work=Plants of the World Online |publisher=Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew |url=https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:306087-2 |access-date=17 January 2019 |archive-date=19 January 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190119121450/http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:306087-2 |url-status=live }}</ref> The genus is widely accepted as being ] to and originating from ].<ref>{{cite book |title=Marijuana and the Cannabinoids |vauthors = ElSohly MA |year=2007 |publisher=Humana Press |isbn=978-1-58829-456-2 |page=8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fxoJPVNKYUgC&pg=PA8|access-date=2 May 2011|archive-date=22 July 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110722061142/http://books.google.com/books?id=fxoJPVNKYUgC&pg=PA8|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Cannabinoids in Nature and Medicine |vauthors = Lambert DM |year=2009|publisher=]|isbn=978-3-906390-56-7 |page=20 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ATDRt1HM9MwC&pg=PA20|access-date=21 August 2018|archive-date=18 August 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210818141634/https://books.google.com/books?id=ATDRt1HM9MwC&pg=PA20|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Ren2021">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ren G, Zhang X, Li Y, Ridout K, Serrano-Serrano ML, Yang Y, Liu A, Ravikanth G, Nawaz MA, Mumtaz AS, Salamin N, Fumagalli L | display-authors = 6 | title = Large-scale whole-genome resequencing unravels the domestication history of ''Cannabis sativa'' | journal = Science Advances | volume = 7 | issue = 29 | pages = eabg2286 | date = July 2021 | pmid = 34272249 | pmc = 8284894 | doi = 10.1126/sciadv.abg2286 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2021SciA....7.2286R |issn = 2375-2548 }}</ref> | |||

| :''This article is about the plant genus ''Cannabis''. For use as a psychoactive drug, see ]. For use as a therapeutic drug, see ]. For non-drug cultivation and uses, see ].'' | |||

| The plant is also known as ], although this term is often used to refer only to ] of ''Cannabis'' ] for non-drug use. Cannabis has long been used for hemp ], ]s and their ], hemp ] for use as ] and as ]. Industrial hemp products are made from cannabis plants selected to produce an abundance of fibre. | |||

| {{Mergefrom|Cannabis sativa|date=June 2007}} | |||

| ''Cannabis'' also has a long history of being used for ], and ] known as ''marijuana'' or ''weed''. Various ]s have been bred, often selectively to produce high or low levels of ] (THC), a ] and the plant's principal ]. Compounds such as ] and ] are extracted from the plant.<ref name="erowid">Erowid. 2006. . {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070423060250/http://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis_basics.shtml |date=23 April 2007 }}. Retrieved on 25 February 2007.</ref> | |||

| == |

==Etymology== | ||

| {{main| |

{{main|Etymology of cannabis}} | ||

| ''Cannabis'' is a ] word.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gray |first1=Stephen |title=Cannabis and Spirituality: An Explorer's Guide to an Ancient Plant Spirit Ally |date=9 December 2016 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-62055-584-2 |page=69 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GmEoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT69 |language=en |quote=Cannabis is called kaneh bosem in Hebrew, which is now recognized as the Scythian word that Herodotus wrote as kánnabis (or cannabis).}}</ref><ref name="r980">{{cite book | last1=Riegel | first1=A. | last2=Ellens | first2=J.H. | title=Seeking the Sacred with Psychoactive Substances: Chemical Paths to Spirituality and to God | publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing | series=Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality | year=2014 | isbn=979-8-216-14310-9 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V6nOEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT80 | access-date=2024-06-03 | page=80}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Duncan |first1=Perry M. |title=Substance Use Disorders: A Biopsychosocial Perspective |date=17 September 2020 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-87777-0 |page=441 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X7H2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA441|language=en |quote=Cannabis is a Scythian word (Benet 1975).}}</ref> The ] learned of the use of cannabis by observing Scythian funerals, during which cannabis was consumed.<ref name="r980" /> In ], cannabis was known as ''qunubu'' ({{lang|akk|𐎯𐎫𐎠𐎭𐏂}}).<ref name="r980" /> The word was adopted in to the ] as ''qaneh bosem'' ({{lang|he|קָנֶה בֹּשׂם}}).<ref name="r980" /> | |||

| The plant name '''cannabis''' is from ] '''{{lang|grc|κάνναβις}}''' (''{{lang|grc|kánnabis}}''), via Latin ''{{lang|la|cannabis}}'', originally a a Scythian or Thracian word, also loaned into Persian as ''{{lang|fa|kanab}}''. English '']'' (Old English {{lang|ags|hænep}}) may be an early loan (predating ]) from the same source. | |||

| ==Description== | |||

| The further origin of the Scythian term is uncertain. It may be of Semitic origin, Hebrew '''קַנַּבּוֹס''' (qannabbôs). | |||

| ]s at the foot of ], ]]] | |||

| ] of wild ''cannabis'' in ], ]]] | |||

| ''Cannabis'' is an ], ], ] ]. The ] are ], with ] ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://waynesword.palomar.edu/termlf1.htm|title=Leaf Terminology (Part 1)|publisher=Waynesword.palomar.edu|access-date=17 February 2011 |archive-date=9 September 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150909114619/http://waynesword.palomar.edu/termlf1.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> The first pair of leaves usually have a single ], the number gradually increasing up to a maximum of about thirteen leaflets per leaf (usually seven or nine), depending on ] and growing conditions. At the top of a ], this number again diminishes to a single leaflet per leaf. The lower leaf pairs usually occur in an opposite ] and the upper leaf pairs in an alternate arrangement on the main stem of a mature plant. | |||

| The leaves have a peculiar and diagnostic ] pattern (which varies slightly among varieties) that allows for easy identification of ''Cannabis'' leaves from unrelated species with similar leaves. As is common in serrated leaves, each serration has a central vein extending to its tip, but in ''Cannabis'' this originates from lower down the central vein of the leaflet, typically opposite to the position of the second notch down. This means that on its way from the midrib of the leaflet to the point of the serration, the vein serving the tip of the serration passes close by the intervening notch. Sometimes the vein will pass tangentially to the notch, but often will pass by at a small distance; when the latter happens a spur vein (or occasionally two) branches off and joins the leaf margin at the deepest point of the notch. Tiny samples of ''Cannabis'' also can be identified with precision by microscopic examination of leaf cells and similar features, requiring special equipment and expertise.<ref name="WattPP">{{cite book | vauthors = Watt JM, Breyer-Brandwijk MG | title = The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa | edition = 2nd | publisher = E & S Livingstone | date = 1962 }}</ref> | |||

| == Description == | |||

| === Reproduction === | |||

| ''Cannabis" also known as, Chronic, Pot, Marijuana, "Dankidy Dank","Cannabis'', herb, weed, gange, mary jane, el presidente, stuff, shiit, beaster, shwag, shwagity shit, is an ], ], ] ]. The ] are ], with ] ]s. The first pair of leaves usually have a single leaflet, the number gradually increasing up to a maximum of about thirteen leaflets per leaf (usually seven or nine), depending on variety and growing conditions. At the top of a flowering plant, this number again diminishes to a single leaflet per leaf. The lower leaf pairs usually occur in an opposite ] and the upper leaf pairs in an alternate arrangement on the main stem of a mature plant. | |||

| All known ] of ''Cannabis'' are ]<ref name="clarke1991a">{{cite book |last1=Clarke RC |title=Marijuana Botany : an advanced study, the propagation and breeding of distinctive Cannabis |date=1981 |publisher=Ronin PuPublishing |location=Berkeley, California |isbn=978-0-914171-78-2 }}{{page needed|date=December 2013}}</ref> and the fruit is an ].<ref name="small1975c">{{cite journal|doi=10.1139/b75-117|title=Morphological variation of achenes of ''Cannabis''|year=1975| vauthors = Small E |journal=Canadian Journal of Botany|volume=53|issue=10|pages=978–87|bibcode=1975CaJB...53..978S }}</ref> Most strains of ''Cannabis'' are ],<ref name=clarke1991a/> with the possible exception of ''C. sativa'' subsp. ''sativa'' var. ''spontanea'' (= ''C. ruderalis''), which is commonly described as "auto-flowering" and may be ]. | |||

| ''Cannabis'' |

''Cannabis'' is predominantly ],<ref name=clarke1991a/><ref name="ainsworth2000">{{cite journal|doi=10.1006/anbo.2000.1201|title=Boys and Girls Come Out to Play: The Molecular Biology of Dioecious Plants|year=2000| vauthors = Ainsworth C |journal=Annals of Botany|volume=86|issue=2|pages=211–221|doi-access=free|bibcode=2000AnBot..86..211A }}</ref> having ] ], with ] "male" and ]late "female" flowers occurring on separate plants.<ref name="lebel1997">{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01012-1|title=Genetics of sex determination in flowering plants|year=1997| vauthors = Lebel-Hardenack S, Grant SR |journal=Trends in Plant Science|volume=2|issue=4|pages=130–6|bibcode=1997TPS.....2..130L }}</ref> "At a very early period the Chinese recognized the ''Cannabis'' plant as dioecious",<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hui-Lin L | date = 1973 | title = The Origin and Use of ''Cannabis'' in Eastern Asia: Linguistic-Cultural Implications | journal = Economic Botany | volume = 28 | issue = 3 | pages = 293–301 (294) }}</ref> and the (c. 3rd century BCE) '']'' dictionary defined ''xi'' ] "male ''Cannabis''" and ''fu'' ] (or ''ju'' ]) "female ''Cannabis''".<ref>13/99 and 13/133. In addition, 13/98 defined ''fen'' 蕡 "''Cannabis'' inflorescence" and 13/159 ''bo'' 薜 "wild ''Cannabis''".</ref> Male flowers are normally borne on loose ]s, and female flowers are borne on ]s.<ref name="bouquet1950">Bouquet, R. J. 1950. . ]. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref> | ||

| Many ] varieties have also been described,<ref name="meijer1999a">{{cite book | vauthors = de Meijer EP | date = 1999 | chapter = ''Cannabis'' germplasm resources. | veditors = Ranalli P | title = Advances in Hemp Research | publisher = Haworth Press | location = Binghamton, NY | pages = 131–151 | isbn = 978-1-56022-872-1 }}</ref> in which individual plants bear both male and female flowers.<ref name="moliterni2005">{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s10681-004-4758-7|title=The sexual differentiation of Cannabis sativa L.: A morphological and molecular study|year=2004| vauthors = Moliterni VC, Cattivelli L, Ranalli P, Mandolino G |journal=Euphytica |volume=140 |issue=1–2 |pages=95–106 |s2cid=11835610}}</ref> (Although monoecious plants are often referred to as "hermaphrodites", true hermaphrodites – which are less common in ''Cannabis'' – bear staminate and pistillate structures together on individual flowers, whereas monoecious plants bear male and female flowers at different locations on the same plant.) ] (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.<ref name="mignoni1999">{{cite web |url=http://www.globalhemp.com/Archives/Government_Research/UN/03_odccp_bulletin.html |vauthors = Mignoni G |date = 1 December 1999 |work = Global Hemp |title=Cannabis as a licit crop: recent developments in Europe |access-date=10 February 2008 |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20030313091047/http://www.globalhemp.com/Archives/Government_Research/UN/03_odccp_bulletin.html |archive-date=13 March 2003 }}</ref><ref name="schumann1999">{{cite journal |vauthors = Schumann E, Peil A, Weber WE |doi=10.1023/A:1008696018533 |year=1999 |title=Preliminary results of a German field trial with different hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) accessions |journal=Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution |volume=46|issue=4|pages=399–407|s2cid=34246180}}</ref><ref name="ranalli2004a">{{cite journal |doi=10.1007/s10681-004-4760-0 |title=Current status and future scenarios of hemp breeding|year=2004| vauthors = Ranalli P |journal=Euphytica |volume=140|issue=1–2 |pages=121–131 |s2cid=26214647}}</ref> Many populations have been described as sexually labile.<ref name="mandolino2002a"/><ref name="hirata1924">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hirata K | year = 1924 | title = Sex reversal in hemp | journal = Journal of the Society of Agriculture and Forestry | volume = 16 | pages = 145–168 }}</ref><ref name="schaffner1931">{{cite journal| vauthors = Schaffner JH |year=1931 |title=The Fluctuation Curve of Sex Reversal in Staminate Hemp Plants Induced by Photoperiodicity|journal=American Journal of Botany |volume=18 |issue=6 |pages=424–30 |jstor=2435878 |doi=10.2307/2435878}}</ref> | |||

| ], ], and other volatile compounds are secreted by glandular ] that occur most abundantly on the floral ]es and ]s of female plants.<ref name="mahlberg2001a">Mahlberg, Paul G. and Eun Soo Kim. 2001. . ''The Hemp Report'' '''3'''(17). Retrieved on 23 Feb 2007</ref> | |||

| As a result of intensive selection in ], ''Cannabis'' exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.<ref name="truta2002a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Truţa E, Gille E, Tóth E, Maniu M | title = Biochemical differences in Cannabis sativa L. depending on sexual phenotype | journal = Journal of Applied Genetics | volume = 43 | issue = 4 | pages = 451–62 | year = 2002 | pmid = 12441630 }}</ref> Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the fruits (produced by female flowers) are used. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate licit crops of monoecious hemp from illicit drug crops,<ref name="mignoni1999"/> but ''sativa'' strains often produce monoecious individuals, which is possibly as a result of ]. | |||

| All known strains of ''Cannabis'' are ]<ref name="clarke1991a">Clarke, Robert C. 1991. ''Marijuana Botany'', 2nd ed. Ron Publishing, California. ISBN 0-914171-78-X</ref> and produce "]s" that are technically called ]s.<ref name="small1975c">Small, E. 1975. Morphological variation of achenes of ''Cannabis''. ''Canadian Journal of Botany'' '''53'''(10): 978-987.</ref> Most strains of ''Cannabis'' are ]s,<ref name=clarke1991a/> with the possible exception of ''C. sativa'' subsp. ''sativa'' var. ''spontanea'' (= ''C. ruderalis''), which is commonly described as "auto-flowering" and may be ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ''Cannabis'' is naturally ], having a ] complement of 2n=20, although polyploid individuals have been artificially produced.<ref name=”small1972a”>Small, E. 1972. Interfertility and chromosomal uniformity in ''Cannabis''. ''Canadian Journal of Botany'' '''50'''(9): 1947-1949.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Cannabis is a genus of flowering plant which includes one or more species. The plant is believed to have originated in the mountainous regions just north west of the Himalayas. It is also known as hemp, although this term usually refers to varieties of Cannabis cultivated for non-drug use. Cannabis plants produce a group of chemicals called cannabinoids which produce mental and physical effects when consumed. As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried buds or flowers(]), ] (]), or various extracts collectively known as ] . In the early 20th century, it became illegal in most of the world to cultivate or possess Cannabis for drug purposes. | |||

| == |

===Sex determination=== | ||

| {{See also|Cytogenetics#History}} | |||

| === Breeding systems === | |||

| ''Cannabis'' has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of ] among the dioecious plants.<ref name="truta2002a"/> Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in ''Cannabis''. | |||

| ] | |||

| ''Cannabis'' is predominantly ],<ref name=clarke1991a/><ref name="ainsworth2000">Ainsworth, C. 2000. . ''Annals of Botany'' '''86'''(2): 211-221. Retrieved on 24 Feb 2007</ref> although many monoecious varieties have been described.<ref name="meijer1999a">de Meijer, E. P. M. 1999. ''Cannabis'' germplasm resources. In: Ranalli P. (ed.). ''Advances in Hemp Research'', Haworth Press, Binghamton, NY, pp. 131-151. ISBN 1-56022-872-5</ref> Subdioecy (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.<ref name="mignoni1999"/><ref name="schumann1999">Schumann, E., A. Peil, and W. E. Weber. 1999. . ''Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution'' '''46'''(4): 399-407. Retrieved on 24 Feb 2007</ref><ref name="ranalli2004a">Ranalli, P. 2004. Current status and future scenarios of hemp breeding. ''Euphytica'' '''140'''(1): 121-131.</ref> Many populations have been described as sexually labile.<ref name="hirata1924">Hirata, K. 1924. Sex reversal in hemp. ''Journal of the Society of Agriculture and Forestry'' '''16''': 145-168.</ref><ref name="schaffner1931">Schaffner, J. H. 1931. The fluctuation curve of sex reversal in staminate hemp plants induced by photoperiodicity. ''American Journal of Botany'' '''18'''(6): 424-430.</ref><ref name="mandolino2002a"/> | |||

| Based on studies of sex reversal in ], it was first reported by K. Hirata in 1924 that an ] is present.<ref name="hirata1924"/> At the time, the XY system was the only known system of sex determination. The ] was first described in '']'' spp in 1925.<ref name="bridges1925">{{cite journal| vauthors = Bridges CB |year= 1925 |title=Sex in Relation to Chromosomes and Genes|journal=The American Naturalist|volume=59|issue=661|pages=127–37|jstor=2456354|doi=10.1086/280023|bibcode= 1925ANat...59..127B |s2cid=84528876}}</ref> Soon thereafter, Schaffner disputed Hirata's interpretation,<ref name="schaffner1929">{{cite journal|hdl=1811/2398| vauthors = Schaffner JH |year=1929|title=Heredity and sex|journal=Ohio Journal of Science|volume=29|issue=1|pages=289–300}}</ref> and published results from his own studies of sex reversal in hemp, concluding that an X:A system was in use and that furthermore sex was strongly influenced by environmental conditions.<ref name="schaffner1931"/> | |||

| As a result of intensive selection in cultivation, ''Cannabis'' exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.<ref name="truta2002a">Truta, E., E. Gille, E. Toth, and M. Maniu. 2002. . ''Journal of Applied Genetics'' '''43'''(4): 451-462. Retrieved on 24 Feb 2007</ref> Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the ] are preferred. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate between licit crops of monoecious hemp and illicit dioecious drug crops.<ref name="mignoni1999"/> | |||

| Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.<ref name="ainsworth2000"/> Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.<ref name="negrutiu2001">{{cite journal | vauthors = Negrutiu I, Vyskot B, Barbacar N, Georgiev S, Moneger F | title = Dioecious plants. A key to the early events of sex chromosome evolution | journal = Plant Physiology | volume = 127 | issue = 4 | pages = 1418–24 | date = December 2001 | pmid = 11743084 | pmc = 1540173 | doi = 10.1104/pp.010711 }}</ref> | |||

| === Mechanisms of sex determination === | |||

| Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for ''Cannabis''. Ainsworth describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage type".<ref name="ainsworth2000"/> | |||

| ''Cannabis'' has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of ] among the dioecious plants.<ref name="truta2002a"/> Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in ''Cannabis''. | |||

| The question of whether heteromorphic ] are indeed present is most conveniently answered if such chromosomes were clearly visible in a ]. ''Cannabis'' was one of the first plant species to be karyotyped; however, this was in a period when karyotype preparation was primitive by modern standards. Heteromorphic sex chromosomes were reported to occur in staminate individuals of dioecious "Kentucky" hemp, but were not found in pistillate individuals of the same variety. Dioecious "Kentucky" hemp was assumed to use an XY mechanism. Heterosomes were not observed in analyzed individuals of monoecious "Kentucky" hemp, nor in an unidentified German cultivar. These varieties were assumed to have sex chromosome composition XX.<ref name="menzel1964">{{cite journal| vauthors = Menzel MY |year=1964|title=Meiotic Chromosomes of Monoecious Kentucky Hemp (Cannabis sativa)|journal=Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club|volume=91|issue=3|pages=193–205|jstor=2483524|doi=10.2307/2483524}}</ref> According to other researchers, no modern karyotype of ''Cannabis'' had been published as of 1996.<ref name="hong1996a">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hong S, Clarke RC |year=1996 |url=http://www.hempfood.com/IHA/iha03207.html |title=Taxonomic studies of Cannabis in China |journal=Journal of the International Hemp Association |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=55–60 |access-date=7 September 2006 |archive-date=9 August 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120809052050/http://www.hempfood.com/iha/iha03207.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Proponents of the XY system state that ] is slightly larger than the X, but difficult to differentiate cytologically.<ref name="peil2003">{{cite journal | vauthors = Peil A, Flachowsky H, Schumann E, Weber WE | title = Sex-linked AFLP markers indicate a pseudoautosomal region in hemp ( Cannabis sativa L.) | journal = Theoretical and Applied Genetics | volume = 107 | issue = 1 | pages = 102–9 | date = June 2003 | pmid = 12835935 | doi = 10.1007/s00122-003-1212-5 | s2cid = 11453369 }}</ref> | |||

| Based on studies of sex reversal in ], it was first reported by K. Hirata in 1924 that an ] is present.<ref name="hirata1924"/> At the time, the XY system was the only known system of sex determination. The ] was first described in Drosophila spp in 1925.<ref name=”bridges1925”>Bridges, C. B. 1925. Sex in relation to chromosomes and genes. ''American Naturalist'' '''59''': 127-137.</ref> Soon thereafter, Schaffner disputed Hirata's interpretation,<ref name="schaffner1929">Schaffner, J. H. 1929. Heredity and sex. ''Ohio Journal of Science'' '''29'''(1): 289-300.</ref> and published results from his own studies of sex reversal in hemp, concluding that an X:A system was in use and that furthermore sex was strongly influenced by environmental conditions.<ref name="schaffner1931"/> | |||

| More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors<ref name="sakamoto1995a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sakamoto K, Shimomura K, Komeda Y, Kamada H, Satoh S | title = A male-associated DNA sequence in a dioecious plant, Cannabis sativa L | journal = Plant & Cell Physiology | volume = 36 | issue = 8 | pages = 1549–54 | date = December 1995 | pmid = 8589931 }}</ref><ref name="sakamoto2005a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sakamoto K, Abe T, Matsuyama T, Yoshida S, Ohmido N, Fukui K, Satoh S | s2cid = 40436657 | title = RAPD markers encoding retrotransposable elements are linked to the male sex in Cannabis sativa L | journal = Genome | volume = 48 | issue = 5 | pages = 931–6 | date = October 2005 | pmid = 16391699 | doi = 10.1139/g05-056 }}</ref> have used ] (RAPD) to isolate several ] sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in ''Cannabis'' (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and ].<ref name="meijer2003a" /><ref name="mandolino2002a" /><ref name="torjek2002">{{cite journal |doi=10.1023/A:1020204729122 |year=2002 | vauthors = Törjék O, Bucherna N, Kiss E, Homoki H, Finta-Korpelová Z, Bócsa I, Nagy I, Heszky LE |journal=Euphytica |volume=127 |issue=2 |pages=209–218|title=Novel male-specific molecular markers (MADC5, MADC6) in hemp|s2cid=27065456 }}</ref> Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating, | |||

| Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.<ref name="ainsworth2000"/> Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.<ref name=”negrutiu2001”> Negrutiu, I., B. Vyskot, N. Barbacar, S. Georgiev, and F. Moneger. 2001. . ''Plant Physiology'' '''127'''(4): 418-424.</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination.<ref name="ainsworth2000" />}} | |||

| Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for ''Cannabis''. Ainsworth<ref name="ainsworth2000"/> describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage-type." | |||

| Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.<ref name="tanurdzic2004">{{cite journal | vauthors = Tanurdzic M, Banks JA | title = Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants | journal = The Plant Cell | volume = 16 | issue = Suppl | pages = S61-71 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15084718 | pmc = 2643385 | doi = 10.1105/tpc.016667 | bibcode = 2004PlanC..16S..61T }}</ref> Many researchers have suggested that sex in ''Cannabis'' is determined or strongly influenced by environmental factors.<ref name=schaffner1931/> Ainsworth reviews that treatment with ] and ] have feminizing effects, and that treatment with ] and ] have masculinizing effects.<ref name=ainsworth2000/> It has been reported that sex can be reversed in ''Cannabis'' using chemical treatment.<ref name="mohanram1982">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mohan Ram HY, Sett R | title = Induction of fertile male flowers in genetically female Cannabis sativa plants by silver nitrate and silver thiosulphate anionic complex | journal = Theoretical and Applied Genetics | volume = 62 | issue = 4 | pages = 369–75 | date = December 1982 | pmid = 24270659 | doi = 10.1007/BF00275107 | s2cid = 12256760 }}</ref> A ]-based method for the detection of female-associated ] by ] has been developed.<ref name=PCR>{{cite journal |doi=10.1300/J237v08n01_02 |title=Female-Associated DNA Polymorphisms of Hemp (Cannabis sativaL.) |year=2003| vauthors = Shao H, Song SJ, Clarke RC |journal=Journal of Industrial Hemp |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=5–9 |s2cid=84460585 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The question of whether heteromorphic sex chromosomes are indeed present is most conveniently answered if such chromosomes were clearly visible in a ]. ''Cannabis'' was one of the first plant species to be karyotyped, however, this was in a period when karyotype preparation was primitive by modern standards (see ]). Heteromorphic sex chromosomes were reported to occur in staminate individuals of dioecious 'Kentucky' hemp, but were not found in pistillate individuals of the same variety. Dioecious 'Kentucky' hemp was assumed to use an XY mechanism. Heterosomes were not observed in analyzed individuals of monoecious 'Kentucky' hemp, nor in an unidentified German cultivar. These varieties were assumed to have sex chromosome composition XX.<ref name="menzel1964">Menzel, Margaret Y. 1964. Meiotic chromosomes of monoecious Kentucky hemp (''Cannabis sativa''). ''Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club'' '''91'''(3): 193-205.</ref> According to other researchers, no modern karyotype of ''Cannabis'' had been published as of 1996.<ref name=”hong1996a”>Shao Hong and Robert C. Clarke. 1996. . ''Journal of the International Hemp Association'' '''3'''(2): 55-60. Retrieved on 25 Feb 2007</ref> Proponents of the XY system state that Y chromosome is slightly larger than the X, but difficult to differentiate cytologically.<ref name="peil2003">Peil, A., H. Flachowsky, E. Schumann, and W. E. Weber. 2003. Sex-linked AFLP markers indicate a pseudoautosomal region in hemp (''Cannabis sativa'' L.). ''Theoretical and Applied Genetics'' '''107'''(1): 102-109.</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="180px" heights="200px"> | |||

| More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors<ref name=”sakamoto1995a”> Sakamoto, K., K. Shimomura, Y. Komeda, H. Kamada, and S. Satoh. 1995. ''Plant & Cell Physiology'' '''36'''(8): 1549-1554. Retrieved on 25 Feb 2007</ref><ref name=”sakamoto2005a”> Sakamoto, K., T. Abe, T. Matsuyama, S. Yoshida, N. Ohmido, K. Fukui, and S. Satoh. 2005. ''Genome'' '''48'''(5): 931-936. Retrieved on 25 Feb 2007</ref> have used ] to isolate several ] sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in Cannabis (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and ].<ref name=”torjek2002”>Törjék, O., N. Bucherna, E. Kiss, H. Homoki, Z. Finta-Korpelová, I. Bócsa, I. Nagy, and L. E. Heszky. 2002. Novel male specific molecular markers (MADC5, MADC6) for sex identification in hemp. ''Euphytica'' '''127''': 209-218.</ref><ref name=mandolino2002a/><ref name=meijer2003a/> Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating that "It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination."<ref name=ainsworth2000/> | |||

| File:Hemp plants-cannabis sativa-single 3.JPG|A male hemp plant | |||

| File:Cannabis indica Selkem.jpg|Dense raceme of female flowers typical of drug-type varieties of ''Cannabis'' | |||

| File:Male Cannabis Lemon Kush (Entire Plant).jpg|Male Lemon Kush cannabis plant (12 foot plant) | |||

| File:Male Lemon Kush Cannabis Plant.jpg|Male Lemon Kush cannabis Flowers | |||

| File:Alcapulco Gold Young Plant.jpg|A young female ] plant (Mexican x Nepalese). Seed grown plant from seeds obtained from a cannabis seed bank.<ref name="r501">{{cite web | last=M. | first=Linda | title=Buy Acapulco Gold Feminized Seeds | website=Seed Supreme | date=2024-08-03 | url=https://seedsupreme.com/acapulco-gold-feminized.html | access-date=2024-08-07}}</ref> | |||

| File:Acapulco Gold Female Plant in Bloom 1.jpg|Acapulco Gold female plant in bloom | |||

| File:Indoor grown Acapulco Gold in Final Stages of Flowering 1.jpg|Indoor grown Acapulco Gold female plant in final stages of flowering (flushing in amber and gold tones) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Chemistry === | |||

| Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.<ref name=”tanurdzic2004”>Tanurdzic, M. and J. A. Banks. 2004. Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants. ''Plant Cell'' '''16''' (suppl.): S61-71.</ref> Many researchers have suggested that sex in ''Cannabis'' is determined or strongly influenced by environmental factors.<ref name=schaffner1931/> Ainsworth reviews that treatment with ] and ] have feminizing effects, and that treatment with ] and ] have masculinizing effects.<ref name=ainsworth2000/> It has been reported that sex can be reversed in ''Cannabis'' using chemical treatment.<ref name=”mohanram1982”>Mohan Ram, H. Y., and R. Sett. 1982. Induction of fertile male flowers in genetically female ''Cannabis sativa'' plants by silver nitrate and silver thiosulfate anionic complex. ''Theoretical and Applied Genetics'' '''62''': 369-375.</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Chemical defenses in Cannabis}} | |||

| A ]-based method for the detection of female-associated ] by ] has been developed | |||

| ''Cannabis'' plants produce a large number of chemicals as part of their ]. One group of these is called ]s, which induce mental and physical ] when ]. | |||

| <ref name="PCR">Journal of Industrial Hemp 2003 Vol 8 issue 1 page 5-9, | |||

| Female-Associated DNA Polymorphisms of Hemp (''Cannabis sativa'' L.), | |||

| Hong Shao, Shu-Juan Song, Robert C. Clarke | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Cannabinoids, ], ], and other compounds are secreted by glandular ]s that occur most abundantly on the floral ] and ]s of female plants.<ref name="mahlberg2001a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mahlberg PG, Eun SK | year = 2001 | title = THC (tetrahyrdocannabinol) accumulation in glands of ''Cannabis'' (Cannabaceae) | url = http://www.hempreport.com/issues/17/malbody17.html | journal = The Hemp Report | volume = 3 | issue = 17 | access-date = 23 November 2006 | archive-date = 29 October 2006 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20061029102500/http://www.hempreport.com/issues/17/malbody17.html | url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| == Aspects of ''Cannabis'' production and use == | |||

| <gallery widths="180px" heights="120px" perrow="3"> | |||

| ] | |||

| File:Cannabis sativa radix profile.png|Root system side view | |||

| File:Cannabis sativa radix topview.png|Root system top view | |||

| File:Cannabis hemp sativa (left) indica (right).png|Micrograph ''C. sativa'' (left), ''C. indica'' (right) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Genetics === | |||

| *] discusses its use as a medication. | |||

| ''Cannabis'', like many organisms, is ], having a ] complement of 2n=20, although ] individuals have been artificially produced.<ref name="small1972a">{{cite journal|doi=10.1139/b72-248|title=Interfertility and chromosomal uniformity in ''Cannabis''|year=1972| vauthors = Small E |journal=Canadian Journal of Botany|volume=50|issue=9|pages=1947–9|bibcode=1972CaJB...50.1947S }}</ref> The first genome sequence of ''Cannabis'', which is estimated to be 820 ] in size, was published in 2011 by a team of Canadian scientists.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = van Bakel H, Stout JM, Cote AG, Tallon CM, Sharpe AG, Hughes TR, Page JE | title = The draft genome and transcriptome of Cannabis sativa | journal = Genome Biology | volume = 12 | issue = 10 | pages = R102 | date = October 2011 | pmid = 22014239 | pmc = 3359589 | doi = 10.1186/gb-2011-12-10-r102 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| *] discusses its use as a recreational ]. | |||

| *] discusses sacramental and religious use. | |||

| *] discusses its uses as a source of ], ], ], ], and industrial materials. | |||

| *] discusses aspects of cultivation for medicinal and recreational drug purposes | |||

| *] focuses on the law and enforcement aspects of growing, transporting, selling and using cannabis as a drug. | |||

| **] | |||

| **] | |||

| *] discusses the ], physical, and mental effects of ''Cannabis'' when used as drug. | |||

| == |

==Taxonomy== | ||

| ]'' leaf, showing diagnostic venation]] | |||

| <!-- ---------------------------------------------------------- | |||

| The genus ''Cannabis'' was formerly placed in the ] family (]) or ] family (]), and later, along with the genus '']'' (]), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae ]).<ref name=schultes2001a>{{cite book | vauthors = Schultes RE, Hofmann A, Rätsch C | date = 2001 | chapter = The nectar of delight. | title = Plants of the Gods | edition = 2nd | publisher = Healing Arts Press | location = Rochester, Vermont | pages = 92–101 | isbn = 978-0-89281-979-9 }}</ref> Recent ] studies based on ] ] analysis and ] strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single ] family, the ] ].<ref name=song2001>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s006060170041|title=Further evidence for paraphyly of the Celtidaceae from the chloroplast gene mat K|year=2001| vauthors = Song BH, Wang XQ, Li FZ, Hong DY |journal=Plant Systematics and Evolution|volume=228|issue=1–2|pages=107–15|bibcode=2001PSyEv.228..107S |s2cid=45337406}}</ref><ref name=sytsma2002>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sytsma KJ, Morawetz J, Pires JC, Nepokroeff M, Conti E, Zjhra M, Hall JC, Chase MW | s2cid = 207690258 | display-authors = 6 | title = Urticalean rosids: circumscription, rosid ancestry, and phylogenetics based on rbcL, trnL-F, and ndhF sequences | journal = American Journal of Botany | volume = 89 | issue = 9 | pages = 1531–46 | date = September 2002 | pmid = 21665755 | doi = 10.3732/ajb.89.9.1531 | doi-access = }}</ref> | |||

| See http://en.wikipedia.org/Wikipedia:Footnotes for a | |||

| discussion of different citation methods and how to generate | |||

| footnotes using the <ref>, </ref> and <reference /> tags | |||

| ----------------------------------------------------------- --> | |||

| <div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> | |||

| <references /></div> | |||

| indica | |||

| Various types of ''Cannabis'' have been described, and variously classified as ], ], or ]:<ref name="small1975b">{{cite journal | vauthors = Small E | title = American law and the species problem in Cannabis: science and semantics | journal = Bulletin on Narcotics | volume = 27 | issue = 3 | pages = 1–20 | year = 1975 | pmid = 1041693 }}</ref> | |||

| == See also== | |||

| * plants cultivated for fiber and seed production, described as low-intoxicant, non-drug, or fiber types. | |||

| *] | |||

| * plants cultivated for drug production, described as high-intoxicant or drug types. | |||

| *] | |||

| * escaped, hybridised, or wild forms of either of the above types. | |||

| *] | |||

| {{Ancient anaesthesia-footer}} | |||

| ''Cannabis'' plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.answers.php?questionID=000636|title=What chemicals are in marijuana and its byproducts?|publisher=ProCon.org|year=2009|access-date=13 January 2013|archive-date=20 January 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130120030619/http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/view.answers.php?questionID=000636|url-status=live}}</ref> and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = El-Alfy AT, Ivey K, Robinson K, Ahmed S, Radwan M, Slade D, Khan I, ElSohly M, Ross S | display-authors = 6 | title = Antidepressant-like effect of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids isolated from Cannabis sativa L | journal = Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior | volume = 95 | issue = 4 | pages = 434–42 | date = June 2010 | pmid = 20332000 | pmc = 2866040 | doi = 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.004 }}</ref> The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are ] (CBD) and/or Δ<sup>9</sup>-] (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.<ref name="pmid19204413">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ahrens J, Demir R, Leuwer M, de la Roche J, Krampfl K, Foadi N, Karst M, Haeseler G | display-authors = 6 | title = The nonpsychotropic cannabinoid cannabidiol modulates and directly activates alpha-1 and alpha-1-Beta glycine receptor function | journal = Pharmacology | volume = 83 | issue = 4 | pages = 217–22 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19204413 | doi = 10.1159/000201556 | s2cid = 13508856 | url = https://www.karger.com/Article/PDF/000201556 | access-date = 18 May 2019 | archive-date = 18 May 2019 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190518161406/https://www.karger.com/Article/PDF/000201556 | url-status = live }}</ref> Since the early 1970s, ''Cannabis'' plants have been categorized by their chemical ] or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.<ref name="small1973a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Small E, Beckstead HD | title = Common cannabinoid phenotypes in 350 stocks of Cannabis | journal = Lloydia | volume = 36 | issue = 2 | pages = 144–65 | date = June 1973 | pmid = 4744553 }}</ref> Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.<ref name="meijer2003a">{{cite journal | vauthors = de Meijer EP, Bagatta M, Carboni A, Crucitti P, Moliterni VM, Ranalli P, Mandolino G | title = The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L | journal = Genetics | volume = 163 | issue = 1 | pages = 335–46 | date = January 2003 | doi = 10.1093/genetics/163.1.335 | pmid = 12586720 | pmc = 1462421 }}</ref> Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F<sub>1</sub>) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.<ref name=small1973a/><ref name="hillig2004a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hillig KW, Mahlberg PG | s2cid = 32469533 | title = A chemotaxonomic analysis of cannabinoid variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae) | journal = American Journal of Botany | volume = 91 | issue = 6 | pages = 966–75 | date = June 2004 | pmid = 21653452 | doi = 10.3732/ajb.91.6.966 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| {{Herbs & spices}} | |||

| {{Cannabis resources}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of ''Cannabis'' constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a ].<ref name="small1979a">{{cite book | vauthors = Small E | date = 1979 | chapter = Fundamental aspects of the species problem in biology. | title = The Species Problem in Cannabis | volume = 1 | publisher = Science. Corpus Information Services | location = Toronto, Canada | pages = 5–63 | isbn = 978-0-919217-11-9 }}</ref> One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."<ref name="glossary">{{cite book | vauthors = Rieger R, Michaelis A, Green MM | date = 1991 | title = Glossary of Genetics | edition = 5th | publisher = Springer-Verlag | pages = 458–459 | isbn = 978-0-387-52054-4 }}</ref> Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.<ref name=glossary/> ] are not known to occur within ''Cannabis'', and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.<ref name="small1972a"/> However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled ''Cannabis'' gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.<ref name="hillig2005a">{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s10722-003-4452-y|title=Genetic evidence for speciation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae)|year=2005| vauthors = Hillig KW |journal=Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution|volume=52|issue=2|pages=161–80|s2cid=24866870}}</ref> It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and ] occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.<ref name="small1975a">{{cite journal| vauthors = Small E |year=1975|url=http://www.botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/psb-1975-21-3.php|title=On toadstool soup and legal species of marihuana|journal=Plant Science Bulletin|volume=21|issue=3|pages=34–9|access-date=28 September 2006|archive-date=27 September 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060927191824/http://www.botany.org/PlantScienceBulletin/psb-1975-21-3.php|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="emboden1981a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Emboden WA | title = The genus Cannabis and the correct use of taxonomic categories | journal = Journal of Psychoactive Drugs | volume = 13 | issue = 1 | pages = 15–21 | year = 1981 | pmid = 7024491 | doi = 10.1080/02791072.1981.10471446 }}</ref><ref name="schultes1980a">{{cite book | vauthors = Schultes RE, Hofmann A | date = 1980 | title = Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens | publisher = C. C. Thomas | location = Springfield, Illinois | pages = 82–116 | isbn = 978-0-398-03863-2 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Early classifications=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The genus ''Cannabis'' was first ] using the "modern" system of taxonomic ] by ] in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.<ref name="linnaeus1753">{{cite book | vauthors = Linnaeus C | orig-date = 1753 | title = Species Plantarum | volume = 2 | page = 1027 | edition = Facsimile | date = 1957–1959 | publisher = Ray SocietyLondon, U.K. (originally Salvius, Stockholm) }}</ref> He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named ''Cannabis sativa'' L.<ref group="a">"L." stands for Linnaeus, and indicates the authority who first named the species</ref> Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classification attempts resulted in a four group division:<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=Lapierre |first1=Éliana |last2=Monthony |first2=Adrian S. |last3=Torkamaneh |first3=Davoud |date=2023-08-01 |title=Genomics-based taxonomy to clarify cannabis classification |journal=Genome |language=en |volume=66 |issue=8 |pages=202–211 |doi=10.1139/gen-2023-0005 |issn=0831-2796|doi-access=free |pmid=37163765 }}</ref> | |||

| * Kif (southern hemp - psychoactive) | |||

| * Vulgaris (intermediate - psychoactive and fiber) | |||

| * Pedemontana (northern hemp - fiber) | |||

| * Chinensis (northern hemp - fiber) | |||

| In 1785, evolutionary biologist ] published a description of a second species of ''Cannabis'', which he named ''Cannabis indica'' Lam.<ref name="lamarck1785">{{cite book | vauthors = de Lamarck JB | date = 1785 | title = Encyclopédie Méthodique de Botanique | volume = 1 | issue = 2 | location = Paris, France | pages = 694–695 }}</ref> Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on morphological aspects (trichomes, leaf shape) and geographic localization of plant specimens collected in India. He described ''C. indica'' as having poorer fiber quality than ''C. sativa'', but greater utility as an ]. Also, ''C. indica'' was considered smaller, by Lamarck. Also, woodier stems, alternate ramifications of the branches, narrow leaflets, and a villous calyx in the female flowers were characteristics noted by the botanist.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (''C. indica'')" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based on a clear distinction between ''C. sativa'' and ''C. indica'', but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as ''indica.<ref name=":1" />'' | |||

| Additional ''Cannabis'' species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names ''Cannabis chinensis'' Delile, and ''Cannabis gigantea'' Delile ex Vilmorin.<ref name="small1976a">{{cite journal| vauthors = Small E, Cronquist A |year=1976|title=A Practical and Natural Taxonomy for Cannabis|journal=Taxon|volume=25|issue=4|pages=405–35|jstor=1220524|doi=10.2307/1220524}}</ref> However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the ], where ''Cannabis'' continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name ''Cannabis indica'' was listed in various ]s, and was widely used to designate ''Cannabis'' suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.<ref name="winek1977">{{cite journal | vauthors = Winek CL | title = Some historical aspects of marijuana | journal = Clinical Toxicology | volume = 10 | issue = 2 | pages = 243–53 | year = 1977 | pmid = 322936 | doi = 10.3109/15563657708987969 }}</ref> | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| {{Further|Feral cannabis}} | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ] ''Cannabis'' in central Russia is either a variety of ''C. sativa'' or a separate species, and proposed ''C. sativa'' L. var. ''ruderalis'' Janisch, and ''Cannabis ruderalis'' Janisch, as alternative names.<ref name=small1975b/> In 1929, renowned plant explorer ] assigned wild or feral populations of ''Cannabis'' in Afghanistan to ''C. indica'' Lam. var. ''kafiristanica'' Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to ''C. sativa'' L. var. ''spontanea'' Vav.<ref name="hillig2004a"/><ref name=small1976a/> Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes ''et al'' (1975)<ref>{{Citation |last1=Schultes |first1=Richard Evans |title=Cannabis: An Example of Taxonomic Neglect |date=1975-12-31 |work=Cannabis and Culture |pages=21–38 |editor-last=Rubin |editor-first=Vera |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110812060.21/html |access-date=2024-07-22 |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |doi=10.1515/9783110812060.21 |isbn=978-90-279-7669-7 |last2=Klein |first2=William M. |last3=Plowman |first3=Timothy |last4=Lockwood |first4=Tom E.}}</ref> and Emboden (1974):<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Emboden |first=William A. |date=1974 |title=Cannabis — a polytypic genus |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF02861427 |journal=Economic Botany |language=en |volume=28 |issue=3 |pages=304–310 |doi=10.1007/BF02861427 |bibcode=1974EcBot..28..304E |issn=0013-0001}}</ref> ''C. sativa'', ''C. indica'' and ''C. ruderalis.<ref name=":1" />'' | |||

| In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized ''C. sativa'' and ''C. indica'' as separate species. Within ''C. sativa'' they recognized two subspecies: ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''culta'' Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''spontanea'' (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two ''C. sativa'' subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies ''culta''. However, they did not divide ''C. indica'' into subspecies or varieties.<ref name="small1975b" /><ref name="serebriakova1940">{{cite book | vauthors = Serebriakova TY, Sizov IA | date = 1940 | chapter = Cannabinaceae Lindl. | veditors = Vavilov NI | title = Kulturnaya Flora SSSR | volume = 5 | location = Moscow-Leningrad, USSR | pages = 1–53 | language = Russian }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Koren |first1=Anamarija |last2=Sikora |first2=Vladimir |last3=Kiprovski |first3=Biljana |last4=Brdar-Jokanović |first4=Milka |last5=Aćimović |first5=Milica |last6=Konstantinović |first6=Bojan |last7=Latković |first7=Dragana |date=2020 |title=Controversial taxonomy of hemp |url=https://doiserbia.nb.rs/Article.aspx?ID=0534-00122001001K |journal=Genetika |volume=52 |issue=1 |pages=1–13 |doi=10.2298/gensr2001001k}}</ref> Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with ''C. sativa'' L. and ''C. ruderalis''.<ref>Zhukovskii, P.M. (1971) ''Cultivated plants and their wild relatives''. 3rd ed. Leningrad, USSR, Kolos.</ref> | |||

| In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of ''Cannabis'' took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting ''Cannabis'' in the ] and ] specifically named products of ''C. sativa'' as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized ''Cannabis'' material may not have been ''C. sativa'', and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while ] and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.<ref name=small1975a/><ref name=emboden1981a/> The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.<ref name="watts2006">{{cite journal | vauthors = Watts G | title = Cannabis confusions | journal = BMJ | volume = 332 | issue = 7534 | pages = 175–6 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16424501 | pmc = 1336775 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.332.7534.175 }}</ref> | |||

| ]In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small<ref name="smallbiography"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070211135642/http://pubs.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/cgi-bin/rp/rp2_gene_e?mlist-authors-small_e.html |date=11 February 2007 }}. National Research Council Canada. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref> and American taxonomist ] published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of ''Cannabis'' with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus: | |||

| * ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''sativa'', presumably ] for traits that enhance fiber or seed production. | |||

| ** ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''sativa'' var. ''sativa'', domesticated variety. | |||

| ** ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''sativa'' var. ''spontanea'' Vav., wild or escaped variety. | |||

| * ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''indica'' (Lam.) Small & Cronq.,<ref name=small1976a/> primarily selected for drug production. | |||

| ** ''C. sativa'' L. subsp. ''indica'' var. ''indica'', domesticated variety. | |||

| ** ''C. sativa'' subsp. ''indica'' var. ''kafiristanica'' (Vav.) Small & Cronq, wild or escaped variety. | |||

| This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of ] characters.<ref name=small1973a/><ref name=small1976a/><ref name="small1976b">{{cite journal| vauthors = Small E, Jui PY, Lefkovitch LP |year=1976|title=A Numerical Taxonomic Analysis of Cannabis with Special Reference to Species Delimitation|journal=Systematic Botany|volume=1|issue=1|pages=67–84|jstor=2418840|doi=10.2307/2418840}}</ref> | |||

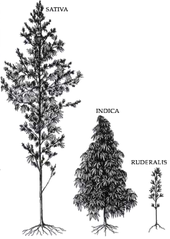

| Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist ] and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of ''Cannabis'' in the 1970s, and concluded that stable ] differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, ''C. sativa'', ''C. indica'', and ''C. ruderalis.''<ref name="schultes1974a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schultes RE, Klein WM, Plowman T, Lockwood TE | year = 1974 | title = ''Cannabis'': an example of taxonomic neglect | journal = Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets | volume = 23 |issue=9 | pages = 337–367 |doi=10.5962/p.168565 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="anderson1974a"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090308011913/http://www.bio.fsu.edu/faculty-anderson.php |date=8 March 2009 }} 1974. A study of systematic wood anatomy in ''Cannabis''. ''Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets'' '''24''': 29–36. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref><ref name="anderson1980a"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090308011913/http://www.bio.fsu.edu/faculty-anderson.php |date=8 March 2009 }} 1980. Leaf variation among ''Cannabis'' species from a controlled garden. ''Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets'' '''28''': 61–69. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref><ref name=emboden1974a>{{cite journal|doi=10.1007/BF02861427|title=Cannabis — a polytypic genus|year=1974| vauthors = Emboden WA |journal=Economic Botany|volume=28|issue=3|pages=304–310|bibcode=1974EcBot..28..304E |s2cid=35358047}}</ref> For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that ''Cannabis'' is monotypic, with only a single species.<ref name="schultes1970a">{{cite book | vauthors = Schultes RE | date = 1970 | chapter = Random thoughts and queries on the botany of ''Cannabis'' | veditors = Joyce CR, Curry SH | title = The Botany and Chemistry of Cannabis | publisher = J. & A. Churchill | location = London | pages = 11–38 }}</ref> According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, ''C. sativa'' is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, ''C. indica'' is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and ''C. ruderalis'' is short, branchless, and grows wild in ]. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by ''Cannabis'' aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.<ref name="clarke2005a">. 1 January 2005. NORML, New Zealand. Retrieved on 19 February 2007</ref> McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.<ref name="pmid30426073"/> | |||

| ===Continuing research=== | |||

| ] developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on ]. Several studies of ] (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of ''Cannabis'', primarily for ] and forensic purposes.<ref name="faeti1996a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mandolino G, Carboni A, Forapani S, Faeti V, Ranalli P |doi=10.1007/s001220051043|title=Identification of DNA markers linked to the male sex in dioecious hemp (Cannabis sativa L.)|year=1999 |journal=Theoretical and Applied Genetics|volume=98|pages=86–92|s2cid=26011527}}</ref><ref name="forapani2001a">{{cite journal|doi=10.2135/cropsci2001.1682|title=Comparison of Hemp Varieties Using Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA Markers|year=2001| vauthors = Forapani S, Carboni A, Paoletti C, Moliterni VM, Ranalli P, Mandolino G |s2cid=29448044|journal=Crop Science|volume=41|issue=6|page=1682|url=http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2e7d/f4b5dd7992dd5ad04d3098aae531fd2d7a28.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220311032503/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2e7d/f4b5dd7992dd5ad04d3098aae531fd2d7a28.pdf |archive-date=2022-03-11 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="mandolino2002a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mandolino G, Ranalli P |doi=10.1300/J237v07n01_03|title=The Applications of Molecular Markers in Genetics and Breeding of Hemp |year=2002 |journal=Journal of Industrial Hemp|volume=7|pages=7–23|s2cid=84960806}}</ref><ref name="gilmore2003a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gilmore S, Peakall R, Robertson J | title = Short tandem repeat (STR) DNA markers are hypervariable and informative in Cannabis sativa: implications for forensic investigations | journal = Forensic Science International | volume = 131 | issue = 1 | pages = 65–74 | date = January 2003 | pmid = 12505473 | doi = 10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00397-3 }}</ref><ref name="kojoka2002a">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kojoma M, Iida O, Makino Y, Sekita S, Satake M | title = DNA fingerprinting of Cannabis sativa using inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR) amplification | journal = Planta Medica | volume = 68 | issue = 1 | pages = 60–3 | date = January 2002 | pmid = 11842329 | doi = 10.1055/s-2002-19875 | s2cid = 260280872 }}</ref> Dutch ''Cannabis'' researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.<ref name="meijer2003a"/> They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the ''Cannabis'' ] throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study ''per se''. | |||

| An investigation of genetic, morphological, and ] variation among 157 ''Cannabis'' accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in ''Cannabis'' ]. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of ''C. sativa'' and ''C. indica'' as separate species, but not ''C. ruderalis''. ''C. sativa'' contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and ]. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to ''C. indica''.<ref name=hillig2004a/> In 2005, a ] of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing ''C. sativa'', ''C. indica'', and (tentatively) ''C. ruderalis''.<ref name="hillig2005a"/> Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the ] of ''Cannabis'' revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain ] alcohols, including ] and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.<ref name="hillig2004b">{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.bse.2004.04.004|title=A chemotaxonomic analysis of terpenoid variation in Cannabis|year=2004| vauthors = Hillig KW |journal=Biochemical Systematics and Ecology|volume=32|issue=10|pages=875–891|bibcode=2004BioSE..32..875H }}</ref><!-- | |||

| As of 2007, taxonomy web sites continue to list ''Cannabis'' as a genus with a single species, whilst listing Cannabis Sativa, Cannabis Indica and Cannabis Ruderalis as subspecies.<ref name="GRIN">USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Program. , National Germplasm Resources Laboratory, Beltsville, Maryland. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref><ref name="APNI">Barlow, Snow. 2006. . Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database. The University of Melbourne. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref><ref name="ITIS">. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref><ref name="taxonomicon">. Universal Taxonomic Services. Retrieved on 23 February 2007</ref>--> | |||

| A 2020 analysis of ]s reports five clusters of ''cannabis'', roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Henry P, Khatodia S, Kapoor K, Gonzales B, Middleton A, Hong K, Hilyard A, Johnson S, Allen D, Chester Z, Jin D, Rodriguez Jule JC, Wilson I, Gangola M, Broome J, Caplan D, Adhikary D, Deyholos MK, Morgan M, Hall OW, Guppy BJ, Orser C | display-authors = 6 | title = A single nucleotide polymorphism assay sheds light on the extent and distribution of genetic diversity, population structure and functional basis of key traits in cultivated north American cannabis | journal = Journal of Cannabis Research | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | pages = 26 | date = September 2020 | pmid = 33526123 | pmc = 7819309 | doi = 10.1186/s42238-020-00036-y | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the ] found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).<ref>{{cite news | vauthors = Ormiston S |date=17 January 2018 |title=What's in your weed: Why cannabis strains don't all live up to their billing |url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/thenational/ormiston-pot-marijuana-cannabis-weed-genetics-1.4489974 |work=CBC |access-date=2 October 2018 |archive-date=1 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181001142449/https://www.cbc.ca/news/thenational/ormiston-pot-marijuana-cannabis-weed-genetics-1.4489974 |url-status=live }} (Paper is {{PMID|26308334}}.)</ref> Legalization of cannabis in Canada ({{as of|2018|October|17|lc=y|df=}}) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://licensedproducerscanada.ca/faq/will-craft-cannabis-growers-in-canada-succeed-like-craft-brewers |title=Will Craft Cannabis Growers in Canada Succeed Like Craft Brewers? |author=<!--Not stated--> |date=<!--Not stated--> |website=Licensed Producers Canada |access-date=2 October 2018 |archive-date=8 May 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190508004314/https://licensedproducerscanada.ca/faq/will-craft-cannabis-growers-in-canada-succeed-like-craft-brewers |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Popular usage=== | |||

| {{hatnote|Popular terms are discerned from scientific taxonomy by the lack of italics, use of quotes and uppercasing.}} | |||

| The scientific debate regarding taxonomy has had little effect on the terminology in widespread use among cultivators and users of drug-type ''Cannabis''. ''Cannabis'' aficionados recognize three distinct types based on such factors as morphology, ], aroma, and subjective psychoactive characteristics. "Sativa" is the most widespread variety, which is usually tall, laxly branched, and found in warm lowland regions. "Indica" designates shorter, bushier plants adapted to cooler climates and highland environments. "Ruderalis" is the informal name for the short plants that grow wild in Europe and Central Asia.<ref name="pmid30426073"/> | |||

| Mapping the morphological concepts to scientific names in the Small 1976 framework, "Sativa" generally refers to ''C. sativa'' subsp. ''indica'' var. ''indica'', "Indica" generally refers to ''C. sativa'' subsp. ''i.'' ''kafiristanica'' (also known as ''afghanica''), and "Ruderalis", being lower in THC, is the one that can fall into ''C. sativa'' subsp. ''sativa''. The three names fit in Schultes's framework better, if one overlooks its inconsistencies with prior work.<ref name="pmid30426073">{{cite journal | vauthors = McPartland JM | title = ''Cannabis'' Systematics at the Levels of Family, Genus, and Species | journal = Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research | volume = 3 | issue = 1 | pages = 203–212 | date = 2018 | pmid = 30426073 | pmc = 6225593 | doi = 10.1089/can.2018.0039 }}</ref> Definitions of the three terms using factors other than morphology produces different, often conflicting results. | |||

| Breeders, seed companies, and cultivators of drug type ''Cannabis'' often describe the ancestry or gross ] characteristics of ]s by categorizing them as "pure indica", "mostly indica", "indica/sativa", "mostly sativa", or "pure sativa". These categories are highly arbitrary, however: one "AK-47" hybrid strain has received both "Best Sativa" and "Best Indica" awards.<ref name="pmid30426073"/> | |||

| === Phylogeny === | |||

| ''Cannabis'' likely split from its closest relative, '']'' (hops), during the mid ], around 27.8 million years ago according to ] estimates. The centre of origin of ''Cannabis'' is likely in the northeastern ]. The pollen of ''Humulus'' and ''Cannabis'' are very similar and difficult to distinguish. The oldest pollen thought to be from ''Cannabis'' is from ], China, on the boundary between the Tibetan Plateau and the ], dating to the early ], around 19.6 million years ago. ''Cannabis'' was widely distributed over Asia by the Late Pleistocene. The oldest known ''Cannabis'' in South Asia dates to around 32,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal| vauthors = McPartland JM, Hegman W, Long T |date=2019-05-14|title=Cannabis in Asia: its center of origin and early cultivation, based on a synthesis of subfossil pollen and archaeobotanical studies|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00334-019-00731-8|journal=Vegetation History and Archaeobotany|volume=28|issue=6|pages=691–702|doi=10.1007/s00334-019-00731-8|bibcode=2019VegHA..28..691M |s2cid=181608199|issn=0939-6314|access-date=19 July 2021|archive-date=11 March 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220311032507/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00334-019-00731-8|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Uses == | |||

| ''Cannabis'' is used for a wide variety of purposes. | |||

| ===History=== | |||

| {{Main|History of cannabis}} | |||

| According to genetic and archaeological evidence, cannabis was first domesticated about 12,000 years ago in ] during the early ] period.<ref name="Ren2021"/> The use of cannabis as a mind-altering drug has been documented by archaeological finds in prehistoric societies in Eurasia and Africa.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Abel E | title = Marijuana, The First 12,000 years | publisher = Plenum Press | location = New York | date = 1980 }}</ref> The oldest written record of cannabis usage is the Greek historian ]'s reference to the central Eurasian ] taking cannabis steam baths.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Butrica JL | date = June 2002 | title = The Medical Use of Cannabis Among the Greeks and Romans | journal = Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics | volume = 2 | issue = 2| pages = 51–70 | doi=10.1300/j175v02n02_04}}</ref> His ({{circa|440 BCE}}) ] records, "The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed , and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Greek vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy."<ref>{{cite web|author=Herodotus | translator-last = Rawlinson G |title=The History of Herodotus|url=http://classics.mit.edu/Herodotus/history.4.iv.html|website=The Internet Classics Archive|publisher=Daniel C. Stevenson, Web Atomics|access-date=13 August 2014|year=1994–2009|archive-date=29 June 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629071015/http://classics.mit.edu/Herodotus/history.4.iv.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Classical Greeks and Romans also used cannabis. | |||

| In China, the psychoactive properties of cannabis are described in the '']'' (3rd century AD).<ref name="Rudgley">{{cite book | veditors = Prance G, Nesbitt M, Rudgley R |date=2005 |title=The Cultural History of Plants |publisher=Routledge |page=198 |isbn=978-0-415-92746-8 }}</ref> Cannabis smoke was inhaled by ]s, who burned it in incense burners.<ref name="Rudgley"/> | |||

| In the Middle East, use spread throughout the Islamic empire to North Africa. In 1545, cannabis spread to the western hemisphere where Spaniards imported it to Chile for its use as fiber. In North America, cannabis, in the form of hemp, was grown for use in rope, cloth and paper.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.deamuseum.org/ccp/cannabis/history.html|title=Cannabis: History|website=deamuseum.org|access-date=8 June 2014|archive-date=17 April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140417065459/http://www.deamuseum.org/ccp/cannabis/history.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Conrad C |title=Hemp : lifeline to the future : the unexpected answer for our environmental and economic recovery |date=1994 |publisher=Creative Xpressions Publications |location=Los Angeles, California |isbn=978-0-9639754-1-6 |edition=2nd}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Herer J | title = Hemp & the marijuana conspiracy : the emperor wears no clothes |date=1992 |publisher=Hemp Pub |location=Van Nuys, CA |isbn=1-878125-00-1 |edition=New, rev. and updated for 1992}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Stafford PG |title=Psychedelics Encyclopedia |date=1992 |publisher=Ronin Publications |location=Berkeley, CA |isbn=978-0-914171-51-5 |edition=3rd expanded}}</ref> | |||

| ] (CBN) was the first compound to be isolated from cannabis extract in the late 1800s. Its structure and chemical synthesis were achieved by 1940, followed by some of the first preclinical research studies to determine the effects of individual cannabis-derived compounds in vivo.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Pertwee |first=Roger G |date=2006 |title=Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years: Cannabinoid pharmacology |journal=British Journal of Pharmacology |language=en |volume=147 |issue=S1 |pages=S163–S171 |doi=10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406 |pmc=1760722 |pmid=16402100}}</ref> | |||

| Globally, in 2013, 60,400 kilograms of cannabis ].<ref name="UN2015">{{cite book |url=https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2014/Narcotic_Drugs_Report_2014.pdf |title=Narcotic Drugs 2014 |date=2015 |publisher=International Narcotics Control Board |isbn=9789210481571 |page=21 |access-date=2 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150602192211/https://www.incb.org/documents/Narcotic-Drugs/Technical-Publications/2014/Narcotic_Drugs_Report_2014.pdf |archive-date=2 June 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Recreational use=== | |||

| {{Main|Cannabis (drug)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Cannabis is a popular recreational drug around the world, only behind alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. In the U.S. alone, it is believed that over 100 million Americans have tried cannabis, with 25 million Americans having used it within the past year.{{when|date=February 2017}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=5442|title=Introduction|publisher=NORML|access-date=17 February 2011|archive-date=11 February 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100211010755/http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=5442|url-status=dead}}</ref> As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried marijuana, ], or various extracts collectively known as ].<ref name="erowid" /> | |||

| Normal cognition is restored after approximately three hours for larger doses via a ], ] or ].<ref name="erowid.org">{{cite web|author=Cannabis|url=http://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis_effects.shtml|title=Erowid Cannabis (Marijuana) Vault : Effects|publisher=Erowid.org|access-date=17 February 2011|archive-date=19 August 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160819023850/https://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis_effects.shtml|url-status=live}}</ref> However, if a large amount is taken orally the effects may last much longer. After 24 hours to a few days, minuscule psychoactive effects may be felt, depending on dosage, frequency and tolerance to the drug. | |||