| Revision as of 03:57, 9 January 2007 editSadi Carnot (talk | contribs)8,673 edits fmt ref← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:43, 22 October 2024 edit undoDirac66 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,924 edits For oxygen, compare with valence bond theory, not with VSEPR which does not deal with diatomic molecules. | ||

| (452 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Method for describing the electronic structure of molecules using quantum mechanics}} | |||

| In ], '''molecular orbital theory''' is a method for determining molecular structure in which ]s are not assigned to individual ]s between ]s, but are treated as moving under the influence of the nuclei in the whole molecule.<ref>{{cite book|author=Daintith, J. |title=Oxford Dictionary of Chemistry|location=New York | publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2004|id=ISBN 0-19-860918-3}}</ref> In this theory, each molecule has a set of ]s, in which it is assumed that the molecular orbital ] ''ψ<sub>f</sub>'' may be written as a simple weighted sum of the constituent atomic orbitals ''χ<sub>i</sub>'', according to the following equation:<ref>{{cite book|author=Licker, Mark, J. |title=McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry|location=New York | publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=2004|id=ISBN 0-07-143953-6}}</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Molecular orbital}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date = February 2019}} | |||

| {{Electronic structure methods}} | |||

| In ], '''molecular orbital theory''' (MO theory or MOT) is a method for describing the electronic structure of molecules using ]. It was proposed early in the 20th century. The MOT explains the ] nature of ], which ] cannot explain. | |||

| :<math> \Psi_j = \sum_i c_{ij} \Chi_i</math> | |||

| In molecular orbital theory, ]s in a molecule are not assigned to individual ]s between ]s, but are treated as moving under the influence of the ] in the whole molecule.<ref>{{cite book|author=Daintith, J. |title=Oxford Dictionary of Chemistry|location=New York | publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-19-860918-6}}</ref> Quantum mechanics describes the spatial and energetic properties of electrons as molecular orbitals that surround two or more atoms in a molecule and contain ]s between atoms. | |||

| The ''c<sub>ij</sub>'' coefficients may be determined numerically by substitution of this equation into the ] and application of the ]. This method is called the ] approximation and is used in ]. Molecular orbital theory is closely related to ]. | |||

| Molecular orbital theory revolutionized the study of chemical bonding by approximating the states of bonded electrons – the molecular orbitals – as ] (LCAO). These approximations are made by applying the ] (DFT) or ] (HF) models to the ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Molecular orbital theory was developed, in the years after valence bond theory (1927) had been established, primarily through the efforts of ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Coulson | first = Charles, A. | title = Valence | publisher = Oxford at the Clarendon Press | year = 1952}}</ref> By 1933, the molecular orbital theory had become accepted as a valid and useful theory.<ref> - Foundations of Molecular Orbital Theory.</ref> According to German physicist and physical chemist ], the first quantitative use of molecular orbital theory was the 1929 paper of Lennard-Jones.<ref>Hückel, E. (1934). ''Trans. Faraday Soc. 30'', 59.</ref> The first accurate calculation of a molecular orbital wavefunction was that made by ] in 1938 on the hydrogen molecule.<ref>Coulson, C.A. (1938). ''Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 34'', 204.</ref> By 1950, ]s were completely defined as ] (wave functions) of the self-consistent field ] and it was at this point that molecular orbital theory became fully rigorous and consistent.<ref>Hall, G.G. Lennard-Jones, Sir John. (1950). ''Proc. Roy. Soc. A202'', 155.</ref> The timeline ] shows the key steps and contributors in the precursory developments to each of these theories, which are both closely intertwined. | |||

| Molecular orbital theory and ] are the foundational theories of ]. | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ] theory (MO) uses a linear combination of ]s to form molecular orbitals which cover the whole molecule. These are often divided into bonding orbitals, ] orbitals, and non-bonding orbitals. A ] is merely a Schrödinger orbital which includes several, but often only two nuclei. If this orbital is of type in which the electron(s) in the orbital have a higher probability of being ''between'' nuclei than elsewhere, the orbital will be a '''bonding''' orbital, and will tend to hold the nuclei together. If the electrons tend to be present in a molecular orbital in which they spend more time elsewhere than between the nuclei, the orbital will function as an ] and will actually weaken the bond. Electrons in non-bonding orbitals tend to be in deep orbitals (nearly ]) associated almost entirely with one nucleus or the other, and thus they spend equal time between nuclei or not. These electrons neither contribute nor detract from bond strength. | |||

| ==Linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) method== | |||

| Molecular orbitals are further divided according the types of atomic orbitals combining to form a bond. These orbitals are results of electron-] interactions that are caused by the ] force of ]. Chemical substances will form a bond if their orbitals become lower in energy when they interact with each other. Different chemical bonds are distinguished that differ by ] and by ]s. | |||

| In the ] method, each molecule has a set of ]s. It is assumed that the molecular orbital ] ''ψ<sub>j</sub>'' can be written as a simple weighted sum of the ''n'' constituent ]s ''χ<sub>i</sub>'', according to the following equation:<ref>{{cite book | author=Licker, Mark, J. |title=McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry | location=New York | publisher=McGraw-Hill| year=2004 | isbn=978-0-07-143953-4}}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block"> \psi_j = \sum_{i=1}^{n} c_{ij} \chi_i.</math> | |||

| MO theory provides a global, delocalized perspective on chemical bonding. For example, in the MO theory for ] molecules, it is no longer necessary to invoke a major role for d-orbitals. In MO theory, ''any'' electron in a molecule may be found ''anywhere'' in the molecule, since quantum conditions allow electrons to travel under the influence of an arbitrarily large number of nuclei, so long as permitted by certain quantum rules. Athough in MO theory ''some'' molecular orbitals may hold electrons which are more localized between specific pairs of molecular atoms, ''other'' orbitals may hold electrons which are spread more uniformly over the molecule. Thus, overall, bonding (and electrons) are far more delocalized (spread out) in MO theory, than is implied in VB theory. This makes MO theory more useful for the description of extended systems. | |||

| One may determine ''c<sub>ij</sub>'' coefficients numerically by substituting this equation into the ] and applying the ]. The variational principle is a mathematical technique used in quantum mechanics to build up the coefficients of each atomic orbital basis. A larger coefficient means that the orbital basis is composed more of that particular contributing atomic orbital – hence, the molecular orbital is best characterized by that type. This method of quantifying orbital contribution as a ] is used in ]. An additional ] can be applied on the system to accelerate the convergence in some computational schemes. Molecular orbital theory was seen as a competitor to ] in the 1930s, before it was realized that the two methods are closely related and that when extended they become equivalent. | |||

| An example is that in the MO picture of ], composed of a hexagonal ring of 6 carbon atoms. In this molecule, 24 of the 30 total valence bonding electrons are located in 12 σ (sigma) bonding orbitals which are mostly located between pairs of atoms (C-C or C-H), similar to the valence bond picture. However, in benzene the remaining 6 bonding electrons are located in 3 π (pi) molecular bonding orbitals that are delocalized around the ring. Two are in a MO which has equal contrinutions from all 6 atoms. The other two have a vertical nodes at right angles to each other. As in the VB theory, all of these 6 delocalized pi electrons reside in a larger space which exists above and below the ring plane. All carbon-carbon bonds in benzene are chemically equivalent. In MO theory this is a direct consequence of the fact that the 3 molecular pi orbitals form a combination which evenly spreads the extra 6 electrons over 6 carbon atoms.<ref> - Imperial College London</ref> | |||

| Molecular orbital theory is used to interpret ] (UV–VIS). Changes to the electronic structure of molecules can be seen by the absorbance of light at specific wavelengths. Assignments can be made to these signals indicated by the transition of electrons moving from one orbital at a lower energy to a higher energy orbital. The molecular orbital diagram for the final state describes the electronic nature of the molecule in an excited state. | |||

| In molecules such as ], the 8 valence electrons are in 4 MOs that are spread out over all 5 atoms. However, it is possible to transform this picture, without altering the total wavefunction and energy, to one with 8 electrons in 4 localised orbitals that are similar to the normal bonding picture of four two-electron covalent bonds. This is what has been done above for the σ (sigma) bonds of benzene, but it is not possible for the π (pi) orbitals. The delocalised picture is more appropriate for ionisation and spectroscopic properties. Upon ionization, a single electron is taken from the whole molecule. The resulting ion does not have one bond different from the other three Similarly for electronic excitations, the electron that is excited is found over the whole molecule and not in one bond. | |||

| There are three main requirements for atomic orbital combinations to be suitable as approximate molecular orbitals. | |||

| As in benzene, in substances such as ], ] or ], some electrons the π (pi) orbitals are spread out in molecular orbitals over long distances in a molecule, giving rise to light absorption in lower energies (visible colors), a fact which is observed. This and other spectroscopic data for molecules are better explained in MO theory, with an emphasis on electronic states associated with multicenter orbitals, including mixing of orbitals premised on principles of orbital symmetry matching. The same MO principles also more naturally explain some electrical phenomena, such as high ] in the planar direction of the hexagonal atomic sheets that exist in ]. In MO theory, "resonance" (a mixing and blending of VB bond states) is a natural consequence of symmetry. For example, in graphite, as in benzene, it is not necessary to invoke the sp<sup>2</sup> hybridization and resonance of VB theory, in order to explain electrical conduction. Instead, MO theory simply recognizes that some electrons in the graphic atomic sheets are completely delocalized over arbitrary distances, and reside in very large ''molecular orbitals'' that cover an entire graphite sheet, and some electrons are thus are as free to move and conduct electricity ''in the sheet plane,'' as if they resided in a ]. | |||

| # The atomic orbital combination must have the correct symmetry, which means that it must belong to the correct ] of the ]. Using ], or SALCs, molecular orbitals of the correct symmetry can be formed. | |||

| ==Timeline== | |||

| # Atomic orbitals must also overlap within space. They cannot combine to form molecular orbitals if they are too far away from one another. | |||

| The following timeline shows the key steps and contributors in the precursory development of molecular orbital theory: | |||

| # Atomic orbitals must be at similar energy levels to combine as molecular orbitals. Because if the energy difference is great, when the molecular orbitals form, the change in energy becomes small. Consequently, there is not enough reduction in energy of electrons to make significant bonding.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Miessler |first1=Gary L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VSktAAAAQBAJ |title=Inorganic Chemistry |last2=Fischer |first2=Paul J. |last3=Tarr |first3=Donald A. |date=2013-04-08 |publisher=Pearson Education |isbn=978-0-321-91779-9 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" |-valign="top" | |||

| |width="4%"|'''Date''' | |||

| == History == | |||

| |width="13%"|'''Person''' | |||

| Molecular orbital theory was developed in the years after ] had been established (1927), primarily through the efforts of ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Coulson | first = Charles, A. | title = Valence | publisher = Oxford at the Clarendon Press | year = 1952}}</ref> MO theory was originally called the Hund-Mulliken theory.<ref name="Mulliken" >{{cite press release |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1966/mulliken-lecture.pdf |orig-year=1966 |year=1972 |author=Mulliken, Robert S.|title=Spectroscopy, Molecular Orbitals, and Chemical Bonding |series=Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1963–1970 |publisher=Elsevier Publishing Company |location=Amsterdam}}</ref> According to physicist and physical chemist ], the first quantitative use of molecular orbital theory was the 1929 paper of ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Hückel |first=Erich |year=1934 |journal=Trans. Faraday Soc. |volume=30 |doi=10.1039/TF9343000040 |title=Theory of free radicals of organic chemistry |pages=40–52}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Lennard-Jones |first=J.E. |year=1929 |journal=Trans. Faraday Soc. |volume=25 |doi= 10.1039/TF9292500668 |title=The electronic structure of some diatomic molecules |pages=668–686|bibcode=1929FaTr...25..668L }}</ref> This paper predicted a ] ground state for the ] which explained its ]<ref>Coulson, C.A. ''Valence'' (2nd ed., Oxford University Press 1961), p.103</ref> (see {{slink|Molecular orbital diagram|Dioxygen}}) before valence bond theory, which came up with its own explanation in 1931.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pauling |first=Linus |year=1931 |journal=J. Am. Chem. Soc. |volume=53 |issue=9 |doi= 10.1021/ja01360a004 |title= The Nature of the Chemical Bond. II. The One-Electron Bond and the Three-Electron Bond. |pages=3225–3237}}</ref> The word ''orbital'' was introduced by Mulliken in 1932.<ref name="Mulliken" /> By 1933, the molecular orbital theory had been accepted as a valid and useful theory.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.quantum-chemistry-history.com/LeJo_Dat/LJ-Hall1.htm |title=The Lennard-Jones paper of 1929 and the foundations of Molecular Orbital Theory |first=George G. |last=Hall |journal=Advances in Quantum Chemistry |volume=22 |pages=1–6 |issn=0065-3276 |isbn=978-0-12-034822-0 |doi=10.1016/S0065-3276(08)60361-5|bibcode = 1991AdQC...22....1H |year=1991 }}</ref> | |||

| |width="83%"|'''Contribution''' | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| Erich Hückel applied molecular orbital theory to unsaturated hydrocarbon molecules starting in 1931 with his ] for the determination of MO energies for ], which he applied to conjugated and aromatic hydrocarbons.<ref>E. Hückel, '']'', '''70''', 204 (1931); '''72''', 310 (1931); '''76''', 628 (1932); '''83''', 632 (1933).</ref><ref>''Hückel Theory for Organic Chemists'', ], B. O'Leary and R. B. Mallion, Academic Press, 1978.</ref> This method provided an explanation of the stability of molecules with six pi-electrons such as ]. | |||

| |'''1838''' | |||

| |] | |||

| The first accurate calculation of a molecular orbital wavefunction was that made by ] in 1938 on the hydrogen molecule.<ref>{{citation |last=Coulson |first=C.A. |author-link=Charles Coulson |title=Self-consistent field for molecular hydrogen |journal=Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society |volume=34 |issue=2 |pages=204–212 |year=1938 |doi=10.1017/S0305004100020089|bibcode = 1938PCPS...34..204C |s2cid=95772081 }}</ref> By 1950, molecular orbitals were completely defined as ] (wave functions) of the self-consistent field ] and it was at this point that molecular orbital theory became fully rigorous and consistent.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1098/rspa.1950.0104 |last=Hall |first=G.G. |journal=Proc. R. Soc. A |volume=202 |pages=336–344 |issue=1070 |date=7 August 1950 |title= The Molecular Orbital Theory of Chemical Valency. VI. Properties of Equivalent Orbitals|bibcode = 1950RSPSA.202..336H |s2cid=123260646 }}</ref> This rigorous approach is known as the ] for molecules although it had its origins in calculations on atoms. In calculations on molecules, the molecular orbitals are expanded in terms of an atomic orbital ], leading to the ].<ref name="Frank">{{cite book |first=Frank |last=Jensen |title=Introduction to Computational Chemistry |publisher=John Wiley and Sons |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-471-98425-2}}</ref> This led to the development of many ]. In parallel, molecular orbital theory was applied in a more approximate manner using some empirically derived parameters in methods now known as ].<ref name="Frank"/> | |||

| |Discovered “]s” when, during an experiment, he passed current through a rarefied air filled glass tube and noticed a strange light arc starting at the ] (positive electrode) and ending at the ] (negative electrode). | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| The success of Molecular Orbital Theory also spawned ], which was developed during the 1930s and 1940s as an alternative to ]. | |||

| |'''1852''' | |||

| |] | |||

| ==Types of orbitals== | |||

| |Initiated the theory of ] by proposing that each element has a specific “combining power”, e.g. some elements such as nitrogen tend to combine with three other elements (e.g. ''NO<sub>3</sub>'') while others may tend to combine with five (e.g. ''PO<sub>5</sub>''), and that each element strives to fulfill it’s combining power (valency) quota so as to satisfy their affinities. | |||

| ] | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| Molecular orbital (MO) theory uses a ] (LCAO) to represent molecular orbitals resulting from bonds between atoms. These are often divided into three types, ], ], and ]. A bonding orbital concentrates electron density in the region ''between'' a given pair of atoms, so that its electron density will tend to attract each of the two nuclei toward the other and hold the two atoms together.<ref name="Tarr 2013">Miessler and Tarr (2013), ''Inorganic Chemistry'', 5th ed, 117-165, 475-534.</ref> An anti-bonding orbital concentrates electron density "behind" each nucleus (i.e. on the side of each atom which is farthest from the other atom), and so tends to pull each of the two nuclei away from the other and actually weaken the bond between the two nuclei. Electrons in non-bonding orbitals tend to be associated with atomic orbitals that do not interact positively or negatively with one another, and electrons in these orbitals neither contribute to nor detract from bond strength.<ref name="Tarr 2013"/> | |||

| |'''1879''' | |||

| |] | |||

| Molecular orbitals are further divided according to the types of ]s they are formed from. Chemical substances will form bonding interactions if their orbitals become lower in energy when they interact with each other. Different bonding orbitals are distinguished that differ by ] (electron cloud shape) and by ]s. | |||

| |Showed that cathode rays (1838), unlike light rays, can be bent in a ]. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

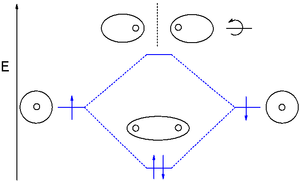

| The molecular orbitals of a molecule can be illustrated in ]s. | |||

| |'''1891''' | |||

| |] | |||

| Common bonding orbitals are ] which are symmetric about the bond axis and ] with a ] along the bond axis. Less common are ] and ] with two and three nodal planes respectively along the bond axis. Antibonding orbitals are signified by the addition of an asterisk. For example, an antibonding pi orbital may be shown as π*. | |||

| |Proposed a theory of ] and valence in which affinity is an attractive force issuing from the center of the atom which acts uniformly from towards all parts of the spherical surface of the central atom. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| == Bond order == | |||

| |'''1892''' | |||

| |] | |||

| ] | |||

| |Showed that cathode rays (1838) could pass through thin sheets of gold foil and produce appreciable luminosity on glass behind them. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| Bond order is the number of chemical bonds between a pair of atoms. The bond order of a molecule can be calculated by subtracting the number of electrons in ] orbitals from the number of ] orbitals, and the resulting number is then divided by two. A molecule is expected to be stable if it has bond order larger than zero. It is adequate to consider the ] to determine the bond order. Because (for ] ''n'' > 1) when MOs are derived from 1s AOs, the difference in number of electrons in bonding and anti-bonding molecular orbital is zero. So, there is no net effect on bond order if the electron is not the valence one. | |||

| |'''1896''' | |||

| |] | |||

| <math>\text{Bond order} = \frac12 (\text{Number of electrons in bonding MO} - \text{Number of electrons in anti-bonding MO})</math> | |||

| |Discovered “]” a process in which, due to nuclear disintegration, certain ]s or ]s spontaneously emit one of three types of energetic entities: ]s (positive charge), ]s (negative charge), and ]s (neutral charge). | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| From bond order, one can predict whether a bond between two atoms will form or not. For example, the existence of He<sub>2</sub> molecule. From the molecular orbital diagram, the bond order is <math display=inline>\frac12(2-2)=0</math>. That means, no bond formation will occur between two He atoms which is seen experimentally. It can be detected under very low temperature and pressure molecular beam and has ] of approximately 0.001 J/mol.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Miessler |first1=Gary L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VSktAAAAQBAJ |title=Inorganic Chemistry |last2=Fischer |first2=Paul J. |last3=Tarr |first3=Donald A. |date=2013-04-08 |publisher=Pearson Education |isbn=978-0-321-91779-9 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| |'''1897''' | |||

| |] | |||

| Besides, the strength of a bond can also be realized from bond order (BO). For example: | |||

| |Showed that cathode rays (1838) bend under the influence of both an ] and a ] and to explain this he suggested that cathode rays are negatively charged subatomic electrical particles or “corpuscles” (]s), stripped from the atom; and in 1904 proposed the “]" in which atoms have a positively charged amorphous mass (pudding) as a body embedded with negatively charged electrons (raisins) scattered throughout in the form of non-random rotating rings. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| For H<sub>2</sub>: Bond order is <math display=inline>\frac12(2-0)=1</math>; bond energy is 436 kJ/mol. | |||

| |'''1900''' | |||

| |] | |||

| For H<sub>2</sub><sup>+</sup>: Bond order is <math display=inline>\frac12(1-0)=\frac12</math>; bond energy is 171 kJ/mol. | |||

| |To explain ] (1862), he suggested that electromagnetic energy could only be emitted in quantized form, i.e. the energy could only be a multiple of an elementary unit ''E = hν'', where ''h'' is ] and ''ν'' is the frequency of the radiation. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| As the bond order of H<sub>2</sub><sup>+</sup> is smaller than H<sub>2</sub>, it should be less stable which is observed experimentally and can be seen from the bond energy. | |||

| |'''1902''' | |||

| |] | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| |To explain the ] (1893), he developed the “]” theory in which electrons in the form of dots were positioned at the corner of a cube and suggested that single, double, or triple “]” result when two atoms are held together by multiple pairs of electrons (one pair for each bond) located between the two atoms (1916). | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=September 2020}} | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| MOT provides a global, delocalized perspective on ]. In MO theory, ''any'' electron in a molecule may be found ''anywhere'' in the molecule, since quantum conditions allow electrons to travel under the influence of an arbitrarily large number of nuclei, as long as they are in eigenstates permitted by certain quantum rules. Thus, when excited with the requisite amount of energy through high-frequency light or other means, electrons can transition to higher-energy molecular orbitals. For instance, in the simple case of a hydrogen diatomic molecule, promotion of a single electron from a bonding orbital to an antibonding orbital can occur under UV radiation. This promotion weakens the bond between the two hydrogen atoms and can lead to photodissociation, the breaking of a chemical bond due to the absorption of light. | |||

| |'''1904''' | |||

| |] | |||

| Molecular orbital theory is used to interpret ] (UV–VIS). Changes to the electronic structure of molecules can be seen by the absorbance of light at specific wavelengths. Assignments can be made to these signals indicated by the transition of electrons moving from one orbital at a lower energy to a higher energy orbital. The molecular orbital diagram for the final state describes the electronic nature of the molecule in an excited state. | |||

| |Noted the pattern that the numerical difference between the maximum positive valence, such as +6 for ''H<sub>2</sub>SO<sub>4</sub>,'' and the maximum negative valence, such as -2 for ''H<sub>2</sub>S'', of an element tends to be eight (]). | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| Although in MO theory ''some'' molecular orbitals may hold electrons that are more localized between specific pairs of molecular atoms, ''other'' orbitals may hold electrons that are spread more uniformly over the molecule. Thus, overall, bonding is far more delocalized in MO theory, which makes it more applicable to resonant molecules that have equivalent non-integer bond orders than ]. This makes MO theory more useful for the description of extended systems. | |||

| |'''1905''' | |||

| |] | |||

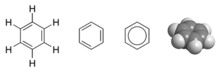

| ], who actively participated in the advent of molecular orbital theory, considers each molecule to be a self-sufficient unit. He asserts in his article: <blockquote>...Attempts to regard a molecule as consisting of specific atomic or ionic units held together by discrete numbers of bonding electrons or electron-pairs are considered as more or less meaningless, except as an approximation in special cases, or as a method of calculation . A molecule is here regarded as a set of nuclei, around each of which is grouped an electron configuration closely similar to that of a free atom in an external field, except that the outer parts of the electron configurations surrounding each nucleus usually belong, in part, jointly to two or more nuclei....<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mulliken|first=R. S.|date=October 1955|title=Electronic Population Analysis on LCAO–MO Molecular Wave Functions. I|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1740588|journal=The Journal of Chemical Physics|volume=23|issue=10|pages=1833–1840|doi=10.1063/1.1740588|bibcode=1955JChPh..23.1833M |issn=0021-9606}}</ref></blockquote>An example is the MO description of ], {{chem|C|6|H|6}}, which is an aromatic hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms and three double bonds. In this molecule, 24 of the 30 total valence bonding electrons – 24 coming from carbon atoms and 6 coming from hydrogen atoms – are located in 12 σ (sigma) bonding orbitals, which are located mostly between pairs of atoms (C–C or C–H), similarly to the electrons in the valence bond description. However, in benzene the remaining six bonding electrons are located in three π (pi) molecular bonding orbitals that are delocalized around the ring. Two of these electrons are in an MO that has equal orbital contributions from all six atoms. The other four electrons are in orbitals with vertical nodes at right angles to each other. As in the VB theory, all of these six delocalized π electrons reside in a larger space that exists above and below the ring plane. All carbon–carbon bonds in benzene are chemically equivalent. In MO theory this is a direct consequence of the fact that the three molecular π orbitals combine and evenly spread the extra six electrons over six carbon atoms. | |||

| |To explain the ] (1839), i.e. that shining light on certain materials can function to eject electrons from the material, he postulated, as based on Planck’s quantum hypothesis (1900), that ] itself consists of individual quantum particles (photons). | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| ] | |||

| |'''1907''' | |||

| In molecules such as ], {{chem|C|H|4}}, the eight valence electrons are found in four MOs that are spread out over all five atoms. It is possible to transform the MOs into four localized sp<sup>3</sup> orbitals. Linus Pauling, in 1931, hybridized the carbon 2s and 2p orbitals so that they pointed directly at the ] 1s basis functions and featured maximal overlap. However, the delocalized MO description is more appropriate for predicting ] and the positions of spectral ]s. When methane is ionized, a single electron is taken from the valence MOs, which can come from the s bonding or the triply degenerate p bonding levels, yielding two ionization energies. In comparison, the explanation in ] is more complicated. When one electron is removed from an sp<sup>3</sup> orbital, ] is invoked between four valence bond structures, each of which has a single one-electron bond and three two-electron bonds. Triply degenerate T<sub>2</sub> and A<sub>1</sub> ionized states (CH<sub>4</sub><sup>+</sup>) are produced from different linear combinations of these four structures. The difference in energy between the ionized and ground state gives the two ionization energies. | |||

| |] | |||

| |To test the plum pudding model (1904), he fired, positively-charged, ]s at gold foil and noticed that some bounced back thus showing that atoms have a small-sized positively charged ] at its center. | |||

| As in benzene, in substances such as ], ], or ], some electrons in the π orbitals are spread out in molecular orbitals over long distances in a molecule, resulting in light absorption in lower energies (the ]), which accounts for the characteristic colours of these substances.<ref name="Griffth 1957">Griffith, J.S. and L.E. Orgel. ''Q. Rev. Chem. Soc.'' 1957, 11, 381-383</ref> This and other spectroscopic data for molecules are well explained in MO theory, with an emphasis on electronic states associated with multicenter orbitals, including mixing of orbitals premised on principles of orbital symmetry matching.<ref name="Tarr 2013"/> The same MO principles also naturally explain some electrical phenomena, such as high ] in the planar direction of the hexagonal atomic sheets that exist in ]. This results from continuous band overlap of half-filled p orbitals and explains electrical conduction. MO theory recognizes that some electrons in the graphite atomic sheets are completely ] over arbitrary distances, and reside in very large molecular orbitals that cover an entire graphite sheet, and some electrons are thus as free to move and therefore conduct electricity in the sheet plane, as if they resided in a metal. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1913''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |To explain the ] (1988), which correctly modeled the light emission spectra of atomic hydrogen, Bohr hypothesized that negatively charged electrons revolve around a positively charged nucleus at certain fixed “quantum” distances and that each of these “spherical orbits” has a specific energy associated with it such that electron movements between orbits requires “quantum” emissions or absorptions of energy. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1916''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |To account for the ] (1896), i.e. that atomic absorption or emission spectral lines change when the light is first shinned through a magnetic field, he suggesting that there might be “elliptical orbits” in atoms in addition to spherical orbits. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1919''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Building on the work of Lewis (1916), he coined the term "covalence" and postulated that ]s occur when the electrons of a pair come from the same atom. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1924''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Postulated that electrons in motion are associated with some kind of waves the lengths of which are given by ] ''h'' divided by the ] of the ''mv = p'' of the ]: ''λ = h / mv = h / p''. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1925''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Outlined the “]” which states that when electrons are added successively to an atom as many levels or orbits are singly occupied as possible before any pairing of electrons with opposite spin occurs and made the distinction that the inner electrons in molecules remained in ]s and only the ]s needed to be in ]s involving both nuclei. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1925''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Outlined the “]” which states that no two identical ]s may occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1926''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Used De Broglie’s electron wave postulate (1924) to develop a “]” that represents mathematically the distribution of a charge of an electron distributed through space, being spherically symmetric or prominent in certain directions, i.e. directed ], which gave the correct values for spectral lines of the hydrogen atom. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1927''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Used Schrödinger’s wave equation (1926) to show how two hydrogen atom ]s join together, with plus, minus, and exchange terms, to form a ]. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1927''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |In 1927 Mulliken worked, in coordination with Hund, to develop a molecular orbital theory where electrons are assigned to states that extend over an entire molecule and in 1932 introduced many new molecular orbital terminologies, such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1928''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Outlined the nature of the ] in which he used Heitler’s quantum mechanical covalent bond model (1927) to outline the ] basis for all types of molecular structure and bonding and suggested that different types of bonds in molecules can become equalized by rapid shifting of electrons, a process called “]” (1931), such that resonance hybrids contain contributions from the different possible electronic configurations. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1929''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Introduced the ] approximation for the calculation of ]s. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1932''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Applied ] to the two-electron problem and showed how ] arising from electron exchange could explain ]. | |||

| |-valign="top" | |||

| |'''1938''' | |||

| |] | |||

| |Made the first accurate calculation of a ] ] with the ]. | |||

| |} | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| {{Portal|Chemistry}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{colbegin}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] (MO theory for transition metal complexes) | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| {{colend}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 140: | Line 100: | ||

| * - Sparknotes | * - Sparknotes | ||

| * - Mark Bishop's Chemistry Site | * - Mark Bishop's Chemistry Site | ||

| * - Queen Mary, London University | * - Queen Mary, London University | ||

| * - a related terms table | * - a related terms table | ||

| * - Oxford University | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Chemical bonding theory}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 12:43, 22 October 2024

Method for describing the electronic structure of molecules using quantum mechanics See also: Molecular orbital

In chemistry, molecular orbital theory (MO theory or MOT) is a method for describing the electronic structure of molecules using quantum mechanics. It was proposed early in the 20th century. The MOT explains the paramagnetic nature of O2, which valence bond theory cannot explain.

In molecular orbital theory, electrons in a molecule are not assigned to individual chemical bonds between atoms, but are treated as moving under the influence of the atomic nuclei in the whole molecule. Quantum mechanics describes the spatial and energetic properties of electrons as molecular orbitals that surround two or more atoms in a molecule and contain valence electrons between atoms.

Molecular orbital theory revolutionized the study of chemical bonding by approximating the states of bonded electrons – the molecular orbitals – as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). These approximations are made by applying the density functional theory (DFT) or Hartree–Fock (HF) models to the Schrödinger equation.

Molecular orbital theory and valence bond theory are the foundational theories of quantum chemistry.

Linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) method

In the LCAO method, each molecule has a set of molecular orbitals. It is assumed that the molecular orbital wave function ψj can be written as a simple weighted sum of the n constituent atomic orbitals χi, according to the following equation:

One may determine cij coefficients numerically by substituting this equation into the Schrödinger equation and applying the variational principle. The variational principle is a mathematical technique used in quantum mechanics to build up the coefficients of each atomic orbital basis. A larger coefficient means that the orbital basis is composed more of that particular contributing atomic orbital – hence, the molecular orbital is best characterized by that type. This method of quantifying orbital contribution as a linear combination of atomic orbitals is used in computational chemistry. An additional unitary transformation can be applied on the system to accelerate the convergence in some computational schemes. Molecular orbital theory was seen as a competitor to valence bond theory in the 1930s, before it was realized that the two methods are closely related and that when extended they become equivalent.

Molecular orbital theory is used to interpret ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–VIS). Changes to the electronic structure of molecules can be seen by the absorbance of light at specific wavelengths. Assignments can be made to these signals indicated by the transition of electrons moving from one orbital at a lower energy to a higher energy orbital. The molecular orbital diagram for the final state describes the electronic nature of the molecule in an excited state.

There are three main requirements for atomic orbital combinations to be suitable as approximate molecular orbitals.

- The atomic orbital combination must have the correct symmetry, which means that it must belong to the correct irreducible representation of the molecular symmetry group. Using symmetry adapted linear combinations, or SALCs, molecular orbitals of the correct symmetry can be formed.

- Atomic orbitals must also overlap within space. They cannot combine to form molecular orbitals if they are too far away from one another.

- Atomic orbitals must be at similar energy levels to combine as molecular orbitals. Because if the energy difference is great, when the molecular orbitals form, the change in energy becomes small. Consequently, there is not enough reduction in energy of electrons to make significant bonding.

History

Molecular orbital theory was developed in the years after valence bond theory had been established (1927), primarily through the efforts of Friedrich Hund, Robert Mulliken, John C. Slater, and John Lennard-Jones. MO theory was originally called the Hund-Mulliken theory. According to physicist and physical chemist Erich Hückel, the first quantitative use of molecular orbital theory was the 1929 paper of Lennard-Jones. This paper predicted a triplet ground state for the dioxygen molecule which explained its paramagnetism (see Molecular orbital diagram § Dioxygen) before valence bond theory, which came up with its own explanation in 1931. The word orbital was introduced by Mulliken in 1932. By 1933, the molecular orbital theory had been accepted as a valid and useful theory.

Erich Hückel applied molecular orbital theory to unsaturated hydrocarbon molecules starting in 1931 with his Hückel molecular orbital (HMO) method for the determination of MO energies for pi electrons, which he applied to conjugated and aromatic hydrocarbons. This method provided an explanation of the stability of molecules with six pi-electrons such as benzene.

The first accurate calculation of a molecular orbital wavefunction was that made by Charles Coulson in 1938 on the hydrogen molecule. By 1950, molecular orbitals were completely defined as eigenfunctions (wave functions) of the self-consistent field Hamiltonian and it was at this point that molecular orbital theory became fully rigorous and consistent. This rigorous approach is known as the Hartree–Fock method for molecules although it had its origins in calculations on atoms. In calculations on molecules, the molecular orbitals are expanded in terms of an atomic orbital basis set, leading to the Roothaan equations. This led to the development of many ab initio quantum chemistry methods. In parallel, molecular orbital theory was applied in a more approximate manner using some empirically derived parameters in methods now known as semi-empirical quantum chemistry methods.

The success of Molecular Orbital Theory also spawned ligand field theory, which was developed during the 1930s and 1940s as an alternative to crystal field theory.

Types of orbitals

Molecular orbital (MO) theory uses a linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) to represent molecular orbitals resulting from bonds between atoms. These are often divided into three types, bonding, antibonding, and non-bonding. A bonding orbital concentrates electron density in the region between a given pair of atoms, so that its electron density will tend to attract each of the two nuclei toward the other and hold the two atoms together. An anti-bonding orbital concentrates electron density "behind" each nucleus (i.e. on the side of each atom which is farthest from the other atom), and so tends to pull each of the two nuclei away from the other and actually weaken the bond between the two nuclei. Electrons in non-bonding orbitals tend to be associated with atomic orbitals that do not interact positively or negatively with one another, and electrons in these orbitals neither contribute to nor detract from bond strength.

Molecular orbitals are further divided according to the types of atomic orbitals they are formed from. Chemical substances will form bonding interactions if their orbitals become lower in energy when they interact with each other. Different bonding orbitals are distinguished that differ by electron configuration (electron cloud shape) and by energy levels.

The molecular orbitals of a molecule can be illustrated in molecular orbital diagrams.

Common bonding orbitals are sigma (σ) orbitals which are symmetric about the bond axis and pi (π) orbitals with a nodal plane along the bond axis. Less common are delta (δ) orbitals and phi (φ) orbitals with two and three nodal planes respectively along the bond axis. Antibonding orbitals are signified by the addition of an asterisk. For example, an antibonding pi orbital may be shown as π*.

Bond order

Bond order is the number of chemical bonds between a pair of atoms. The bond order of a molecule can be calculated by subtracting the number of electrons in anti-bonding orbitals from the number of bonding orbitals, and the resulting number is then divided by two. A molecule is expected to be stable if it has bond order larger than zero. It is adequate to consider the valence electron to determine the bond order. Because (for principal quantum number n > 1) when MOs are derived from 1s AOs, the difference in number of electrons in bonding and anti-bonding molecular orbital is zero. So, there is no net effect on bond order if the electron is not the valence one.

From bond order, one can predict whether a bond between two atoms will form or not. For example, the existence of He2 molecule. From the molecular orbital diagram, the bond order is . That means, no bond formation will occur between two He atoms which is seen experimentally. It can be detected under very low temperature and pressure molecular beam and has binding energy of approximately 0.001 J/mol.

Besides, the strength of a bond can also be realized from bond order (BO). For example:

For H2: Bond order is ; bond energy is 436 kJ/mol.

For H2: Bond order is ; bond energy is 171 kJ/mol.

As the bond order of H2 is smaller than H2, it should be less stable which is observed experimentally and can be seen from the bond energy.

Overview

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

MOT provides a global, delocalized perspective on chemical bonding. In MO theory, any electron in a molecule may be found anywhere in the molecule, since quantum conditions allow electrons to travel under the influence of an arbitrarily large number of nuclei, as long as they are in eigenstates permitted by certain quantum rules. Thus, when excited with the requisite amount of energy through high-frequency light or other means, electrons can transition to higher-energy molecular orbitals. For instance, in the simple case of a hydrogen diatomic molecule, promotion of a single electron from a bonding orbital to an antibonding orbital can occur under UV radiation. This promotion weakens the bond between the two hydrogen atoms and can lead to photodissociation, the breaking of a chemical bond due to the absorption of light.

Molecular orbital theory is used to interpret ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–VIS). Changes to the electronic structure of molecules can be seen by the absorbance of light at specific wavelengths. Assignments can be made to these signals indicated by the transition of electrons moving from one orbital at a lower energy to a higher energy orbital. The molecular orbital diagram for the final state describes the electronic nature of the molecule in an excited state.

Although in MO theory some molecular orbitals may hold electrons that are more localized between specific pairs of molecular atoms, other orbitals may hold electrons that are spread more uniformly over the molecule. Thus, overall, bonding is far more delocalized in MO theory, which makes it more applicable to resonant molecules that have equivalent non-integer bond orders than valence bond theory. This makes MO theory more useful for the description of extended systems.

Robert S. Mulliken, who actively participated in the advent of molecular orbital theory, considers each molecule to be a self-sufficient unit. He asserts in his article:

...Attempts to regard a molecule as consisting of specific atomic or ionic units held together by discrete numbers of bonding electrons or electron-pairs are considered as more or less meaningless, except as an approximation in special cases, or as a method of calculation . A molecule is here regarded as a set of nuclei, around each of which is grouped an electron configuration closely similar to that of a free atom in an external field, except that the outer parts of the electron configurations surrounding each nucleus usually belong, in part, jointly to two or more nuclei....

An example is the MO description of benzene, C

6H

6, which is an aromatic hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms and three double bonds. In this molecule, 24 of the 30 total valence bonding electrons – 24 coming from carbon atoms and 6 coming from hydrogen atoms – are located in 12 σ (sigma) bonding orbitals, which are located mostly between pairs of atoms (C–C or C–H), similarly to the electrons in the valence bond description. However, in benzene the remaining six bonding electrons are located in three π (pi) molecular bonding orbitals that are delocalized around the ring. Two of these electrons are in an MO that has equal orbital contributions from all six atoms. The other four electrons are in orbitals with vertical nodes at right angles to each other. As in the VB theory, all of these six delocalized π electrons reside in a larger space that exists above and below the ring plane. All carbon–carbon bonds in benzene are chemically equivalent. In MO theory this is a direct consequence of the fact that the three molecular π orbitals combine and evenly spread the extra six electrons over six carbon atoms.

In molecules such as methane, CH

4, the eight valence electrons are found in four MOs that are spread out over all five atoms. It is possible to transform the MOs into four localized sp orbitals. Linus Pauling, in 1931, hybridized the carbon 2s and 2p orbitals so that they pointed directly at the hydrogen 1s basis functions and featured maximal overlap. However, the delocalized MO description is more appropriate for predicting ionization energies and the positions of spectral absorption bands. When methane is ionized, a single electron is taken from the valence MOs, which can come from the s bonding or the triply degenerate p bonding levels, yielding two ionization energies. In comparison, the explanation in valence bond theory is more complicated. When one electron is removed from an sp orbital, resonance is invoked between four valence bond structures, each of which has a single one-electron bond and three two-electron bonds. Triply degenerate T2 and A1 ionized states (CH4) are produced from different linear combinations of these four structures. The difference in energy between the ionized and ground state gives the two ionization energies.

As in benzene, in substances such as beta carotene, chlorophyll, or heme, some electrons in the π orbitals are spread out in molecular orbitals over long distances in a molecule, resulting in light absorption in lower energies (the visible spectrum), which accounts for the characteristic colours of these substances. This and other spectroscopic data for molecules are well explained in MO theory, with an emphasis on electronic states associated with multicenter orbitals, including mixing of orbitals premised on principles of orbital symmetry matching. The same MO principles also naturally explain some electrical phenomena, such as high electrical conductivity in the planar direction of the hexagonal atomic sheets that exist in graphite. This results from continuous band overlap of half-filled p orbitals and explains electrical conduction. MO theory recognizes that some electrons in the graphite atomic sheets are completely delocalized over arbitrary distances, and reside in very large molecular orbitals that cover an entire graphite sheet, and some electrons are thus as free to move and therefore conduct electricity in the sheet plane, as if they resided in a metal.

See also

- Cis effect

- Configuration interaction

- Coupled cluster

- Frontier molecular orbital theory

- Ligand field theory (MO theory for transition metal complexes)

- Møller–Plesset perturbation theory

- Quantum chemistry computer programs

- Semi-empirical quantum chemistry methods

- Valence bond theory

References

- Daintith, J. (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Chemistry. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860918-6.

- Licker, Mark, J. (2004). McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-143953-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miessler, Gary L.; Fischer, Paul J.; Tarr, Donald A. (2013-04-08). Inorganic Chemistry. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-321-91779-9.

- Coulson, Charles, A. (1952). Valence. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mulliken, Robert S. (1972) . "Spectroscopy, Molecular Orbitals, and Chemical Bonding" (PDF) (Press release). Nobel Lectures, Chemistry 1963–1970. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company.

- Hückel, Erich (1934). "Theory of free radicals of organic chemistry". Trans. Faraday Soc. 30: 40–52. doi:10.1039/TF9343000040.

- Lennard-Jones, J.E. (1929). "The electronic structure of some diatomic molecules". Trans. Faraday Soc. 25: 668–686. Bibcode:1929FaTr...25..668L. doi:10.1039/TF9292500668.

- Coulson, C.A. Valence (2nd ed., Oxford University Press 1961), p.103

- Pauling, Linus (1931). "The Nature of the Chemical Bond. II. The One-Electron Bond and the Three-Electron Bond". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 53 (9): 3225–3237. doi:10.1021/ja01360a004.

- Hall, George G. (1991). "The Lennard-Jones paper of 1929 and the foundations of Molecular Orbital Theory". Advances in Quantum Chemistry. 22: 1–6. Bibcode:1991AdQC...22....1H. doi:10.1016/S0065-3276(08)60361-5. ISBN 978-0-12-034822-0. ISSN 0065-3276.

- E. Hückel, Zeitschrift für Physik, 70, 204 (1931); 72, 310 (1931); 76, 628 (1932); 83, 632 (1933).

- Hückel Theory for Organic Chemists, C. A. Coulson, B. O'Leary and R. B. Mallion, Academic Press, 1978.

- Coulson, C.A. (1938), "Self-consistent field for molecular hydrogen", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 34 (2): 204–212, Bibcode:1938PCPS...34..204C, doi:10.1017/S0305004100020089, S2CID 95772081

- Hall, G.G. (7 August 1950). "The Molecular Orbital Theory of Chemical Valency. VI. Properties of Equivalent Orbitals". Proc. R. Soc. A. 202 (1070): 336–344. Bibcode:1950RSPSA.202..336H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1950.0104. S2CID 123260646.

- ^ Jensen, Frank (1999). Introduction to Computational Chemistry. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-98425-2.

- ^ Miessler and Tarr (2013), Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed, 117-165, 475-534.

- Miessler, Gary L.; Fischer, Paul J.; Tarr, Donald A. (2013-04-08). Inorganic Chemistry. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-321-91779-9.

- Mulliken, R. S. (October 1955). "Electronic Population Analysis on LCAO–MO Molecular Wave Functions. I". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 23 (10): 1833–1840. Bibcode:1955JChPh..23.1833M. doi:10.1063/1.1740588. ISSN 0021-9606.

- Griffith, J.S. and L.E. Orgel. "Ligand Field Theory". Q. Rev. Chem. Soc. 1957, 11, 381-383

External links

- Molecular Orbital Theory - Purdue University

- Molecular Orbital Theory - Sparknotes

- Molecular Orbital Theory - Mark Bishop's Chemistry Site

- Introduction to MO Theory - Queen Mary, London University

- Molecular Orbital Theory - a related terms table

- An introduction to Molecular Group Theory - Oxford University

| Chemical bonding theory | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of bonds |

| ||||||

| Valence bond theory |

| ||||||

| Molecular orbital theory |

| ||||||

. That means, no bond formation will occur between two He atoms which is seen experimentally. It can be detected under very low temperature and pressure molecular beam and has

. That means, no bond formation will occur between two He atoms which is seen experimentally. It can be detected under very low temperature and pressure molecular beam and has  ; bond energy is 436 kJ/mol.

; bond energy is 436 kJ/mol.

; bond energy is 171 kJ/mol.

; bond energy is 171 kJ/mol.