| Revision as of 05:39, 7 October 2010 edit24.98.122.134 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:44, 7 October 2010 edit undoLex2006 (talk | contribs)27 editsmNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

| In the EU, the European Medicines Agency has issued a release recommending that member states suspend marketing authorization for this product in the treatment of acute (not chronic) back pain.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/press/pr/Pressrelease_Carisoprodol_52046307en.pdf |format=PDF|title=Carisprodol press release |publisher= EMEA |accessdate=2008-05-12}}</ref> | In the EU, the European Medicines Agency has issued a release recommending that member states suspend marketing authorization for this product in the treatment of acute (not chronic) back pain.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/press/pr/Pressrelease_Carisoprodol_52046307en.pdf |format=PDF|title=Carisprodol press release |publisher= EMEA |accessdate=2008-05-12}}</ref> | ||

| In the United States, while carisoprodol is not a ] under federal regulations, as of February 2010, carisoprodol is considered to be a schedule IV controlled substance by the states of Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon and Texas (scheduled using the state's new controlled substance program which requires physicians to obtain, and include, a state "DPS" number as well as a DEA number on all controlled substances prescriptions), Utah,<ref name="Utah house bill 30"></ref> and Washington State. It is a Schedule III controlled substance in West Virginia.<ref>Respective state Boards of Pharmacy and controlled substance authorities.</ref> The rest of the United States, excluding the above named states, falls under the DEA scheduling for the medication, which considers carisoprodol a non-scheduled chemical, meaning that carisoprodol is considered a general prescription medication by the ], with oversight provided solely by the ] (FDA).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flsenate.gov/data/session/2002/House/bills/analysis/pdf/2002h0351z.cpcs.pdf|format=PDF|title=Florida Senate House Bill 351}}</ref> | In the United States, while carisoprodol is not a ] under federal regulations, as of February 2010, carisoprodol is considered to be a schedule IV controlled substance by the states of Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon and Texas (scheduled using the state's new controlled substance program which requires physicians to obtain, and include, a state "DPS" number as well as a DEA number on all controlled substances prescriptions), Utah,<ref name="Utah house bill 30"></ref> and Washington State. It is a Schedule III controlled substance in West Virginia.<ref>Respective state Boards of Pharmacy and controlled substance authorities.</ref> The rest of the United States, excluding the above named states, falls under the DEA scheduling for the medication, which considers carisoprodol a non-scheduled chemical, meaning that carisoprodol is considered a general prescription medication by the ], with oversight provided solely by the ] (FDA).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flsenate.gov/data/session/2002/House/bills/analysis/pdf/2002h0351z.cpcs.pdf|format=PDF|title=Florida Senate House Bill 351}}</ref> The actions of these state simply prohibit the sale via remote prescription. This does not stop legally acting pharmacies like www.netmedorders.com from dispensing these to other locations without a problem and within the bounds of the law. | ||

| On March 26, 2010 the DEA issued a ] on proposed rule making in respect to the placement of | On March 26, 2010 the DEA issued a ] on proposed rule making in respect to the placement of | ||

Revision as of 23:44, 7 October 2010

Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 60% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C19-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.017 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H24N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 260.33 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

| (verify) | |

Carisoprodol is a centrally-acting skeletal muscle relaxant. It is a colorless, crystalline powder, having a mild characteristic odor and a bitter taste. Carisoprodol is slightly soluble in water and freely soluble in alcohol, chloroform and acetone. The drug's solubility is practically independent of pH. Carisoprodol is manufactured and marketed in the United States by Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc. under the brand name SOMA, and in the United Kingdom and other countries under the brand names Sanoma and Carisoma. The drug is available by itself or mixed with aspirin and in one preparation (Soma Compound With Codeine) along with codeine and caffeine as well.

History

On June 1, 1959 several American pharmacologists convened at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan to discuss a new drug. The drug, originally thought to have antiseptic properties, was found to have central muscle relaxing properties. It had been developed by Dr. Frank M. Berger at Wallace Laboratories and was named carisoprodol.

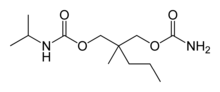

Carisoprodol was developed on the basis of meprobamate, in the hope that it would have better muscle relaxing properties, less potential for abuse, and less risk of overdose than meprobamate. The substitution of one hydrogen atom with an isopropyl group on one of the carbamyl nitrogens was intended to yield a molecule with new pharmacological properties.

The brand name Soma is shared with the Soma/Haoma of ancient India, a drug mentioned in ancient Sanskrit writings. Various classical and modern researchers have theorised that Soma/Haoma could be anything from ephedra or opium to mushrooms of the genus Amanita with hallucinogenic effects due to the anti-muscarinic drugs contained therein, or other anti-cholinergic-drug containing plant—or a still unknown hallucinogen, stimulant and/or narcotic of unknown chemical class and origin or even coca or other drugs ported from the Western Hemisphere by an as yet unknown pre-Viking, pre-Columbian contact.

Soma is also the name of the fictional drug featured in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.

Usage and Legal Status

Although reports from Norway have shown that carisoprodol has abuse potential as a prodrug of meprobamate and/or potentiator of hydrocodone, dihydrocodeine, codeine and similar drugs, it continues to be prescribed in North America, alongside orphenadrine and cyclobenzaprine. In Europe, doctors favor cyclobenzaprine. In the United Kingdom, benzodiazepines are preferred instead. All of the above plus chlorzoxazone are used in Canada.

As of November 2007, carisoprodol (Somadril, Somadril comp.) has been taken off the market in Sweden due to problems with dependence and side effects. The agency overseeing pharmaceuticals has considered other drugs used with the same indications as carisoprodol to have the same or better effects without the risks of the drug. In May 2008 it was taken off the market in Norway as well.

In the EU, the European Medicines Agency has issued a release recommending that member states suspend marketing authorization for this product in the treatment of acute (not chronic) back pain.

In the United States, while carisoprodol is not a controlled substance under federal regulations, as of February 2010, carisoprodol is considered to be a schedule IV controlled substance by the states of Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon and Texas (scheduled using the state's new controlled substance program which requires physicians to obtain, and include, a state "DPS" number as well as a DEA number on all controlled substances prescriptions), Utah, and Washington State. It is a Schedule III controlled substance in West Virginia. The rest of the United States, excluding the above named states, falls under the DEA scheduling for the medication, which considers carisoprodol a non-scheduled chemical, meaning that carisoprodol is considered a general prescription medication by the federal government of the United States, with oversight provided solely by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The actions of these state simply prohibit the sale via remote prescription. This does not stop legally acting pharmacies like www.netmedorders.com from dispensing these to other locations without a problem and within the bounds of the law.

On March 26, 2010 the DEA issued a Notice of Hearing on proposed rule making in respect to the placement of carisoprodol in schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act.

Chemistry

Carisoprodol is a carbamic acid ester. It is a racemic mixture of two stereoisomers.

Effects

- Analgesia

- Anxiolysis

- Muscle relaxation (and relief from hypertonia)

- Sedation

- Somnolence

Side effects

The usual dose of 350 mg is unlikely to engender prominent side effects other than somnolence. The medication is well tolerated and without adverse effects in the majority of patients for which it is indicated. In some patients however, and/or early in therapy, carisoprodol can have the full spectrum of sedative side effects and can impair the patient's ability to operate a firearm, motorcycle, and other machinery of various types especially when taken with medications containing alcohol, in which case an alternative medication would be considered. The intensity of the side effects of carisoprodol tends to lessen as therapy continues, as is the case with many other drugs.

The interaction of carisoprodol with opioids, essentially all opioids and other centrally-acting analgesics, but especially those of the codeine-derived subgroup of the semi-synthetic class (codeine, ethylmorphine, dihydrocodeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, nicocodeine, benzylmorphine, the various acetylated codeine derivatives including thebacon and acetyldihydrocodeine, dihydroisocodeine, nicodicodeine and others) which allows the use of a smaller dose of the opioid to have a given effect, is useful in general and especially where injury and/or muscle spasm is a large part of the problem. The potentiation effect is also useful in other pain situations and is also especially useful with opioids of the open-chain class such as methadone, levomethadone, ketobemidone, phenadoxone and others. In recreational drug users, deaths have resulted from carelessly combining overdoses of hydrocodone and carisoprodol.

Meprobamate and other muscle relaxing drugs often were subjects of misuse and abuse in the 1950s and 1960s. Overdose cases were reported as early as 1957 and have been reported on several occasions since then.

Carisoprodol, meprobamate, and related drugs such as tybamate have the potential to produce physical dependence with prolonged use. Withdrawal of the drug after extensive use may require hospitalization in medically-compromised patients.

Because of potential for more severe side effects, this drug is on the list to avoid in the elderly. (See NCQA’s HEDIS Measure: Use of High Risk Medications in the Elderly, http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/SOHC/Drugs_Avoided_Elderly.pdf).

Pharmacokinetics

Carisoprodol has a rapid, 30 minute onset of action, with the aforementioned effects lasting for approximately 2–6 hours. It is metabolized in the liver via the cytochrome P450 oxidase isozyme CYP2C19, excreted by the kidneys and has an approximate 8 hour half-life. A considerable proportion of carisoprodol is metabolized to meprobamate, which is a known drug of abuse and dependence; this could account for the abuse potential of carisoprodol.

Notes

References

- Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc. of Somerset, New Jersey is the U.S. subsidiary of Meda AB of Solna, Sweden "Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc". Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- Miller JG, ed. The pharmacology and clinical usefulness of carisoprodol. Detroit:Wayne State University; 1959.

- Berger F, Kletzkin M, Ludwig B, Margolin S. The history, chemistry, and pharmacology of carisoprodol. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1959;86:90-107

- "Brave New Soma - TIME". Time. 1959-06-08. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- Bramness JG, Furu K, Engeland A, . (2007). "Carisoprodol use and abuse in Norway. A pharmacoepidemiological study". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 64 (2): 210–218. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02847.x. PMC 2000626. PMID 17298482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|vol=ignored (|volume=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Marknadsföringen av Somadril och Somadril comp rekommenderas upphöra tillfälligt". 16 NOV 2007. Retrieved 9 MAY 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - "Somadril trekkes fra markedet". 20 April 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Carisprodol press release" (PDF). EMEA. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- Respective state Boards of Pharmacy and controlled substance authorities.

- "Florida Senate House Bill 351" (PDF).

- Kamin I, Shaskan D. (1959). "Death due to massive overdose of meprobamate". Am J Psychiatry. 115 (12): 1123–1124. PMID 13649976.

- Hollister LE (1983). "The pre-benzodiazepine era". J Psychoactive Drugs. 15 (1–2): 9–13. PMID 6350551.

- Gaillard Y, Billault F, Pepin G (1997). "Meprobamate overdosage: a continuing problem. Sensitive GC-MS quantitation after solid phase extraction in 19 fatal cases". Forensic Sci.Int. 86 (3): 173–180. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(97)02128-2. PMID 9180026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Allen MD, Greenblatt DJ, Noel BJ (1977). "Meprobamate overdosage: a continuing problem". Clin Toxicol. 11 (5): 501–515. doi:10.3109/15563657708988216. PMID 608316.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kintz P, Tracqui A, Mangin P, Lugnier AA (1988). "Fatal meprobamate self-poisoning". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 9 (2): 139–140. doi:10.1097/00000433-198806000-00009. PMID 3381792.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eeckhout E, Huyghens L, Loef B, Maes V, Sennesael J (1988). "Meprobamate poisoning, hypotension and the Swan-Ganz catheter". Intensive Care Med. 14 (4): 437–438. doi:10.1007/BF00262904. PMID 3403779.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lhoste F, Lemaire F, Rapin M (1977). "Treatment of hypotension in meprobamate poisoning". N Engl J Med. 296 (17): 1004. doi:10.1056/NEJM197704282961717.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bedson H (1959). "Coma due to meprobamate intoxication. Report of a case confirmed by chemical analysis". Lancet. 273 (1): 288–290. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90209-0.

- Blumberg A, Rosett H, Dobrow A (1959). "Severe hypotension reactions following meprobamate overdosage". Ann Intern Med. 51: 607–612. PMID 13801701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Drug information

- Drug information for Patients, Drug information for Professionals

- "SOMA 250 mg (carisoprodol) for Painful Musculoskeletal Conditions". Meda Pharmaceuticals Inc. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)

| Skeletal muscle relaxants (M03) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripherally acting (primarily antinicotinic, NMJ block) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Centrally acting |

| ||||||||||||||

| Directly acting | |||||||||||||||