| Revision as of 23:25, 29 August 2016 editEdwardUK (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users66,736 editsm fixed infobox error← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:34, 21 January 2017 edit undoTAnthony (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors853,150 edits →Plot: copyedit, so "attractiveness" and "filial devotion" don't seem attributed to ShuichiNext edit → | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| Shingo observes and questions his relations with his family members, his wife Yasuko, his philandering son Shuichi, his daughter-in-law Kikuko, and his married daughter Fusako, who has left her husband and returned to her family home with her two young daughters. Shingo realizes that he has not truly been an involved and loving husband and father, and perceives the marital difficulties of his adult children to be the fruit of his poor parenting. | Shingo observes and questions his relations with his family members, his wife Yasuko, his philandering son Shuichi, his daughter-in-law Kikuko, and his married daughter Fusako, who has left her husband and returned to her family home with her two young daughters. Shingo realizes that he has not truly been an involved and loving husband and father, and perceives the marital difficulties of his adult children to be the fruit of his poor parenting. | ||

| To this end, he begins to question his secretary, Tanizaki Eiko, about his son's affair, as she knows Shuichi socially and is friends with his mistress, and he quietly puts pressure upon Shuichi to quit his infidelity. At the same time, he becomes aware that he has begun to experience a fatherly yet erotic attachment to Kikuko, whose quiet suffering in the face of her husband's unfaithfulness |

To this end, he begins to question his secretary, Tanizaki Eiko, about his son's affair, as she knows Shuichi socially and is friends with his mistress, and he quietly puts pressure upon Shuichi to quit his infidelity. At the same time, he becomes aware that he has begun to experience a fatherly yet erotic attachment to Kikuko, whose physical attractiveness, filial devotion, and quiet suffering in the face of her husband's unfaithfulness contrast strongly with the bitter resentment and homeliness of Shingo's own daughter, Fusako. Complicating matters in his own marriage is the infatuation he once possessed for Yasuko's older sister, more beautiful than Yasuko, who died as a young woman but now appears in his dreams along with other dead friends and associates. | ||

| The novel can be interpreted as a meditation of aging and its attendant decline, and coming to terms with one's mortality. Even as Shingo regrets not being present for his family and blames himself for his children's failing marriages, the natural world comes alive for him in a whole new way, provoking meditations on life, love, and companionship. | The novel can be interpreted as a meditation of aging and its attendant decline, and coming to terms with one's mortality. Even as Shingo regrets not being present for his family and blames himself for his children's failing marriages, the natural world comes alive for him in a whole new way, provoking meditations on life, love, and companionship. | ||

Revision as of 14:34, 21 January 2017

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "The Sound of the Mountain" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

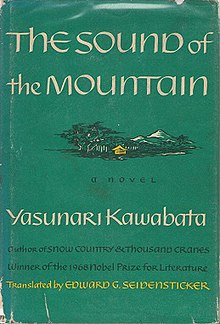

First English-language edition First English-language edition | |

| Author | Yasunari Kawabata |

|---|---|

| Original title | 山の音 Yama no Oto |

| Translator | Edward Seidensticker |

| Language | Japanese |

| Publication date | 1949–1954 |

| Publication place | Japan |

| Published in English | 1970 (Knopf) |

| Media type | Print (paperback) |

The Sound of the Mountain (Yama no Oto) is a novel by Japanese writer Yasunari Kawabata, serialized between 1949 and 1954. The Sound of the Mountain is unusually long for a Kawabata novel, running to 276 pages in its English translation. Like much of his work, it is written in short, spare prose akin to poetry, which its English-language translator Edward Seidensticker likened to a haiku in the introduction to his translation of Kawabata's best-known novel, Snow Country.

Sound of the Mountain was adapted as a film of the same name (Toho, 1954), directed by Mikio Naruse and starring Setsuko Hara, So Yamamura, Ken Uehara and Yatsuko Tanami.

The book is included in the Bokklubben World Library's list of the 100 greatest works of world literature.

For the first U.S. edition (1970), Seidensticker won the National Book Award in category Translation.

Plot

The novel centers upon the Ogata family of Kamakura, and its events are witnessed from the perspective of its aging patriarch, Shingo, a businessman close to retirement who works in Tokyo. Shingo is experiencing temporary lapses of memory, recalling strange and disturbing dreams upon waking, and hearing sounds, including the titular noise which awakens him from his sleep, "like wind, far away, but with a depth like a rumbling of the earth." Shingo takes the sound to be an omen of his impending death.

Shingo observes and questions his relations with his family members, his wife Yasuko, his philandering son Shuichi, his daughter-in-law Kikuko, and his married daughter Fusako, who has left her husband and returned to her family home with her two young daughters. Shingo realizes that he has not truly been an involved and loving husband and father, and perceives the marital difficulties of his adult children to be the fruit of his poor parenting.

To this end, he begins to question his secretary, Tanizaki Eiko, about his son's affair, as she knows Shuichi socially and is friends with his mistress, and he quietly puts pressure upon Shuichi to quit his infidelity. At the same time, he becomes aware that he has begun to experience a fatherly yet erotic attachment to Kikuko, whose physical attractiveness, filial devotion, and quiet suffering in the face of her husband's unfaithfulness contrast strongly with the bitter resentment and homeliness of Shingo's own daughter, Fusako. Complicating matters in his own marriage is the infatuation he once possessed for Yasuko's older sister, more beautiful than Yasuko, who died as a young woman but now appears in his dreams along with other dead friends and associates.

The novel can be interpreted as a meditation of aging and its attendant decline, and coming to terms with one's mortality. Even as Shingo regrets not being present for his family and blames himself for his children's failing marriages, the natural world comes alive for him in a whole new way, provoking meditations on life, love, and companionship.

References

-

"National Book Awards – 1971". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

There was a "Translation" award from 1967 to 1983.

| Works by Yasunari Kawabata | |

|---|---|

| Novels |

|

| Short stories |

|

| Adaptations |

|