This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 24.150.184.249 (talk) at 19:39, 17 January 2018 (→Derivation: tried correcting). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:39, 17 January 2018 by 24.150.184.249 (talk) (→Derivation: tried correcting)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Causal dynamical triangulation (abbreviated as CDT) theorized by Renate Loll, Jan Ambjørn and Jerzy Jurkiewicz, and popularized by Fotini Markopoulou and Lee Smolin, is an approach to quantum gravity that like loop quantum gravity is background independent.

This means that it does not assume any pre-existing arena (dimensional space), but rather attempts to show how the spacetime fabric itself evolves.

The Loops '05 conference, hosted by many loop quantum gravity theorists, included several presentations which discussed CDT in great depth, and revealed it to be a pivotal insight for theorists. It has sparked considerable interest as it appears to have a good semi-classical description. At large scales, it re-creates the familiar 4-dimensional spacetime, but it shows spacetime to be 2-d near the Planck scale, and reveals a fractal structure on slices of constant time. These interesting results agree with the findings of Lauscher and Reuter, who use an approach called Quantum Einstein Gravity, and with other recent theoretical work. A brief article appeared in the February 2007 issue of Scientific American, which gives an overview of the theory, explained why some physicists are excited about it, and put it in historical perspective. The same publication gives CDT, and its primary authors, a feature article in its July 2008 issue.

Introduction

Near the Planck scale, the structure of spacetime itself is supposed to be constantly changing due to quantum fluctuations and topological fluctuations . CDT theory uses a triangulation process which varies dynamically and follows deterministic rules, to map out how this can evolve into dimensional spaces similar to that of our universe.

The results of researchers suggest that this is a good way to model the early universe, and describe its evolution. Using a structure called a simplex, it divides spacetime into tiny triangular sections. A simplex is the multidimensional analogue of a triangle; a 3-simplex is usually called a tetrahedron, while the 4-simplex, which is the basic building block in this theory, is also known as the pentachoron. Each simplex is geometrically flat, but simplices can be "glued" together in a variety of ways to create curved spacetimes, where previous attempts at triangulation of quantum spaces have produced jumbled universes with far too many dimensions, or minimal universes with too few.

CDT avoids this problem by allowing only those configurations in which the timelines of all joined edges of simplices agree.

Derivation

CDT is a modification of quantum Regge calculus where spacetime is discretized by approximating it with a piecewise linear manifold in a process called triangulation. In this process, a d-dimensional spacetime is considered as formed by space slices that are labeled by a discrete time variable t. Each space slice is approximated by a simplicial manifold composed by regular (d − 1)-dimensional simplices and the connection between these slices is made by a piecewise linear manifold of d-simplices. In place of a smooth manifold there is a network of triangulation nodes, where space is locally flat (within each simplex) but globally curved, as with the individual faces and the overall surface of a geodesic dome. The line segments which make up each triangle can represent either a space-like or time-like extent, depending on whether they lie on a given time slice, or connect a vertex at time t with one at time t + 1. The crucial development is that the network of simplices is constrained to evolve in a way that preserves causality. This allows a path integral to be calculated non-perturbatively, by summation of all possible (allowed) configurations of the simplices, and correspondingly, of all possible spatial geometries.

Simply put, each individual simplex is like a building block of spacetime, but the edges that have a time arrow must agree in direction, wherever the edges are joined. This rule preserves causality, a feature missing from previous "triangulation" theories. thumb|Triangulation of a Torus When simplexes are joined in this way, the complex evolves in an orderly fashion, and eventually creates the observed framework of dimensions. CDT builds upon the earlier work of Barrett and Crane, and Baez and Barret, but by introducing the causality constraint as a fundamental rule (influencing the process from the very start), Loll, Ambjørn, and Jurkiewicz created something different.

Advantages and disadvantages

CDT derives the observed nature and properties of spacetime from a small set of assumptions, without adjusting factors. The idea of deriving what is observed from first principles is very attractive to physicists. CDT models the character of spacetime both in the ultra-microscopic realm near the Planck scale, and at the scale of the cosmos, so CDT may provide insights into the nature of reality.

Evaluation of the observable implications of CDT relies heavily on Monte Carlo simulation by computer. Some feel that this makes CDT an inelegant quantum gravity theory. Also, it has been argued that discrete time-slicing may not accurately reproduce all possible modes of a dynamical system. However, research by Markopoulou and Smolin demonstrates that the cause for those concerns may be limited. Therefore, many physicists still regard this line of reasoning as promising.

Related theories

CDT has some similarities with loop quantum gravity, especially with its spin foam formulations. For example, the Lorentzian Barrett–Crane model is essentially a non-perturbative prescription for computing path integrals, just like CDT. There are important differences, however. Spin foam formulations of quantum gravity use different degrees of freedom and different Lagrangians. For example, in CDT, the distance, or "the interval", between any two points in a given triangulation can be calculated exactly (triangulations are eigenstates of the distance operator). This is not true for spin foams or loop quantum gravity in general.

Another approach to quantum gravity that is closely related to causal dynamical triangulation is called causal sets. Both CDT and causal sets attempt to model the spacetime with a discrete causal structure. The main difference between the two is that the causal set approach is relatively general, whereas CDT assumes a more specific relationship between the lattice of spacetime events and geometry. Consequently, the Lagrangian of CDT is constrained by the initial assumptions to the extent that it can be written down explicitly and analyzed (see, for example, hep-th/0505154, page 5), whereas there is more freedom in how one might write down an action for causal-set theory.

See also

- Asymptotic safety in quantum gravity

- Causal sets

- Fractal cosmology

- Loop quantum gravity

- 5-cell

- Planck scale

- Quantum gravity

- Regge calculus

- Simplex

- Simplicial manifold

- Spin foam

References

- Quantum gravity: progress from an unexpected direction

- Jan Ambjørn, Jerzy Jurkiewicz, and Renate Loll - "The Self-Organizing Quantum Universe", Scientific American, July 2008

- Alpert, Mark "The Triangular Universe" Scientific American page 24, February 2007

- Ambjørn, J.; Jurkiewicz, J.; Loll, R. - Quantum Gravity or the Art of Building Spacetime

- Loll, R.; Ambjørn, J.; Jurkiewicz, J. - The Universe from Scratch - a less technical recent overview

- Loll, R.; Ambjørn, J.; Jurkiewicz, J. - Reconstructing the Universe - a technically detailed overview

- Markopoulou, Fotini; Smolin, Lee - Gauge Fixing in Causal Dynamical Triangulations - shows that varying the time-slice gives similar results

Early papers on the subject:

- R. Loll, Discrete Lorentzian Quantum Gravity, arXiv:hep-th/0011194v1 21 Nov 2000

- J Ambjørn, A. Dasgupta, J. Jurkiewicz, and R. Loll, A Lorentzian cure for Euclidean troubles, arXiv:hep-th/0201104 v1 14 Jan 2002

- Causal dynamical triangulation on arxiv.org

External links

- Renate Loll's talk at Loops '05

- John Baez' talk at Loops '05

- Pentatope: from MathWorld

- Simplex: from MathWorld

- Tetrahedron: from MathWorld

- (Re-)Constructing the Universe from Renate Loll's homepage

- Renate Loll on the Quantum Origins of Space and Time as broadcast by TVO

| Theories of gravitation | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard |

| ||||||||||||

| Alternatives to general relativity |

| ||||||||||||

| Pre-Newtonian theories and toy models | |||||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||||

| Quantum gravity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central concepts | |||||||||

| Toy models | |||||||||

| Quantum field theory in curved spacetime | |||||||||

| Black holes | |||||||||

| Approaches |

| ||||||||

| Applications | |||||||||

| See also: | |||||||||

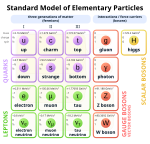

| Standard Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background |  | ||||||||

| Constituents | |||||||||

| Beyond the Standard Model |

| ||||||||

| Experiments | |||||||||