In mathematics, the Lambert W function, also called the omega function or product logarithm, is a multivalued function, namely the branches of the converse relation of the function f(w) = we, where w is any complex number and e is the exponential function. The function is named after Johann Lambert, who considered a related problem in 1758. Building on Lambert's work, Leonhard Euler described the W function per se in 1783.

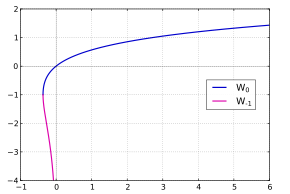

For each integer k there is one branch, denoted by Wk(z), which is a complex-valued function of one complex argument. W0 is known as the principal branch. These functions have the following property: if z and w are any complex numbers, then

holds if and only if

When dealing with real numbers only, the two branches W0 and W−1 suffice: for real numbers x and y the equation

can be solved for y only if x ≥ −1/e; yields y = W0(x) if x ≥ 0 and the two values y = W0(x) and y = W−1(x) if −1/e ≤ x < 0.

The Lambert W function's branches cannot be expressed in terms of elementary functions. It is useful in combinatorics, for instance, in the enumeration of trees. It can be used to solve various equations involving exponentials (e.g. the maxima of the Planck, Bose–Einstein, and Fermi–Dirac distributions) and also occurs in the solution of delay differential equations, such as y′(t) = a y(t − 1). In biochemistry, and in particular enzyme kinetics, an opened-form solution for the time-course kinetics analysis of Michaelis–Menten kinetics is described in terms of the Lambert W function.

Terminology

The notation convention chosen here (with W0 and W−1) follows the canonical reference on the Lambert W function by Corless, Gonnet, Hare, Jeffrey and Knuth.

The name "product logarithm" can be understood as this: Since the inverse function of f(w) = e is called the logarithm, it makes sense to call the inverse "function" of the product we as "product logarithm". (Technical note: like the complex logarithm, it is multivalued and thus W is described as the converse relation rather than inverse function.) It is related to the omega constant, which is equal to W0(1).

History

Lambert first considered the related Lambert's Transcendental Equation in 1758, which led to an article by Leonhard Euler in 1783 that discussed the special case of we.

The equation Lambert considered was

Euler transformed this equation into the form

Both authors derived a series solution for their equations.

Once Euler had solved this equation, he considered the case . Taking limits, he derived the equation

He then put and obtained a convergent series solution for the resulting equation, expressing in terms of .

After taking derivatives with respect to and some manipulation, the standard form of the Lambert function is obtained.

In 1993, it was reported that the Lambert function provides an exact solution to the quantum-mechanical double-well Dirac delta function model for equal charges—a fundamental problem in physics. Prompted by this, Rob Corless and developers of the Maple computer algebra system realized that "the Lambert W function has been widely used in many fields, but because of differing notation and the absence of a standard name, awareness of the function was not as high as it should have been."

Another example where this function is found is in Michaelis–Menten kinetics.

Although it was widely believed that the Lambert function cannot be expressed in terms of elementary (Liouvillian) functions, the first published proof did not appear until 2008.

Elementary properties, branches and range

There are countably many branches of the W function, denoted by Wk(z), for integer k; W0(z) being the main (or principal) branch. W0(z) is defined for all complex numbers z while Wk(z) with k ≠ 0 is defined for all non-zero z. With W0(0) = 0 and limz→0 Wk(z) = −∞ for all k ≠ 0.

The branch point for the principal branch is at z = −1/e, with a branch cut that extends to −∞ along the negative real axis. This branch cut separates the principal branch from the two branches W−1 and W1. In all branches Wk with k ≠ 0, there is a branch point at z = 0 and a branch cut along the entire negative real axis.

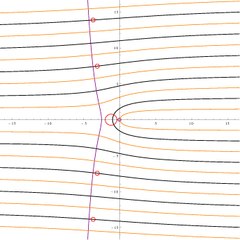

The functions Wk(z), k ∈ Z are all injective and their ranges are disjoint. The range of the entire multivalued function W is the complex plane. The image of the real axis is the union of the real axis and the quadratrix of Hippias, the parametric curve w = −t cot t + it.

Inverse

The range plot above also delineates the regions in the complex plane where the simple inverse relationship is true. implies that there exists an such that , where depends upon the value of . The value of the integer changes abruptly when is at the branch cut of , which means that ≤ 0, except for where it is ≤ −1/.

Defining , where and are real, and expressing in polar coordinates, it is seen that

For , the branch cut for is the non-positive real axis, so that

and

For , the branch cut for is the real axis with , so that the inequality becomes

Inside the regions bounded by the above, there are no discontinuous changes in , and those regions specify where the function is simply invertible, i.e. .

Calculus

Derivative

By implicit differentiation, one can show that all branches of W satisfy the differential equation

(W is not differentiable for z = −1/e.) As a consequence, that gets the following formula for the derivative of W:

Using the identity e = z/W(z), gives the following equivalent formula:

At the origin we have

Integral

The function W(x), and many other expressions involving W(x), can be integrated using the substitution w = W(x), i.e. x = we:

(The last equation is more common in the literature but is undefined at x = 0). One consequence of this (using the fact that W0(e) = 1) is the identity

Asymptotic expansions

The Taylor series of W0 around 0 can be found using the Lagrange inversion theorem and is given by

The radius of convergence is 1/e, as may be seen by the ratio test. The function defined by this series can be extended to a holomorphic function defined on all complex numbers with a branch cut along the interval (−∞, −1/e]; this holomorphic function defines the principal branch of the Lambert W function.

For large values of x, W0 is asymptotic to

where L1 = ln x, L2 = ln ln x, and is a non-negative Stirling number of the first kind. Keeping only the first two terms of the expansion,

The other real branch, W−1, defined in the interval [−1/e, 0), has an approximation of the same form as x approaches zero, with in this case L1 = ln(−x) and L2 = ln(−ln(−x)).

Integer and complex powers

Integer powers of W0 also admit simple Taylor (or Laurent) series expansions at zero:

More generally, for r ∈ Z, the Lagrange inversion formula gives

which is, in general, a Laurent series of order r. Equivalently, the latter can be written in the form of a Taylor expansion of powers of W0(x) / x:

which holds for any r ∈ C and |x| < 1/e.

Bounds and inequalities

A number of non-asymptotic bounds are known for the Lambert function.

Hoorfar and Hassani showed that the following bound holds for x ≥ e:

They also showed the general bound

for every and , with equality only for . The bound allows many other bounds to be made, such as taking which gives the bound

In 2013 it was proven that the branch W−1 can be bounded as follows:

Roberto Iacono and John P. Boyd enhanced the bounds as follows:

Identities

A few identities follow from the definition:

Note that, since f(x) = xe is not injective, it does not always hold that W(f(x)) = x, much like with the inverse trigonometric functions. For fixed x < 0 and x ≠ −1, the equation xe = ye has two real solutions in y, one of which is of course y = x. Then, for i = 0 and x < −1, as well as for i = −1 and x ∈ (−1, 0), y = Wi(xe) is the other solution.

Some other identities:

-

- (which can be extended to other n and x if the correct branch is chosen).

Substituting −ln x in the definition:

With Euler's iterated exponential h(x):

Special values

The following are special values of the principal branch:

- (the omega constant)

Special values of the branch W−1:

Representations

The principal branch of the Lambert function can be represented by a proper integral, due to Poisson:

Another representation of the principal branch was found by Kalugin–Jeffrey–Corless:

The following continued fraction representation also holds for the principal branch:

Also, if |W0(x)| < 1:

In turn, if |W0(x)| > e, then

Other formulas

Definite integrals

There are several useful definite integral formulas involving the principal branch of the W function, including the following:

The first identity can be found by writing the Gaussian integral in polar coordinates.

The second identity can be derived by making the substitution u = W0(x), which gives

Thus

The third identity may be derived from the second by making the substitution u = x and the first can also be derived from the third by the substitution z = 1/√2 tan x.

Except for z along the branch cut (−∞, −1/e] (where the integral does not converge), the principal branch of the Lambert W function can be computed by the following integral:

where the two integral expressions are equivalent due to the symmetry of the integrand.

Indefinite integrals

1st proof

Introduce substitution variable

Proof

Proof

Introduce substitution variable , which gives us and

Applications

Solving equations

The Lambert W function is used to solve equations in which the unknown quantity occurs both in the base and in the exponent, or both inside and outside of a logarithm. The strategy is to convert such an equation into one of the form ze = w and then to solve for z using the W function.

For example, the equation

(where x is an unknown real number) can be solved by rewriting it as

This last equation has the desired form and the solutions for real x are:

and thus:

Generally, the solution to

is:

where a, b, and c are complex constants, with b and c not equal to zero, and the W function is of any integer order.

Viscous flows

Granular and debris flow fronts and deposits, and the fronts of viscous fluids in natural events and in laboratory experiments can be described by using the Lambert–Euler omega function as follows:

where H(x) is the debris flow height, x is the channel downstream position, L is the unified model parameter consisting of several physical and geometrical parameters of the flow, flow height and the hydraulic pressure gradient.

In pipe flow, the Lambert W function is part of the explicit formulation of the Colebrook equation for finding the Darcy friction factor. This factor is used to determine the pressure drop through a straight run of pipe when the flow is turbulent.

Time-dependent flow in simple branch hydraulic systems

The principal branch of the Lambert W function is employed in the field of mechanical engineering, in the study of time dependent transfer of Newtonian fluids between two reservoirs with varying free surface levels, using centrifugal pumps. The Lambert W function provided an exact solution to the flow rate of fluid in both the laminar and turbulent regimes: where is the initial flow rate and is time.

Neuroimaging

The Lambert W function is employed in the field of neuroimaging for linking cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption changes within a brain voxel, to the corresponding blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal.

Chemical engineering

The Lambert W function is employed in the field of chemical engineering for modeling the porous electrode film thickness in a glassy carbon based supercapacitor for electrochemical energy storage. The Lambert W function provides an exact solution for a gas phase thermal activation process where growth of carbon film and combustion of the same film compete with each other.

Crystal growth

In the crystal growth, the negative principal of the Lambert W-function can be used to calculate the distribution coefficient, , and solute concentration in the melt, , from the Scheil equation:

Materials science

The Lambert W function is employed in the field of epitaxial film growth for the determination of the critical dislocation onset film thickness. This is the calculated thickness of an epitaxial film, where due to thermodynamic principles the film will develop crystallographic dislocations in order to minimise the elastic energy stored in the films. Prior to application of Lambert W for this problem, the critical thickness had to be determined via solving an implicit equation. Lambert W turns it in an explicit equation for analytical handling with ease.

Porous media

The Lambert W function has been employed in the field of fluid flow in porous media to model the tilt of an interface separating two gravitationally segregated fluids in a homogeneous tilted porous bed of constant dip and thickness where the heavier fluid, injected at the bottom end, displaces the lighter fluid that is produced at the same rate from the top end. The principal branch of the solution corresponds to stable displacements while the −1 branch applies if the displacement is unstable with the heavier fluid running underneath the lighter fluid.

Bernoulli numbers and Todd genus

The equation (linked with the generating functions of Bernoulli numbers and Todd genus):

can be solved by means of the two real branches W0 and W−1:

This application shows that the branch difference of the W function can be employed in order to solve other transcendental equations.

Statistics

The centroid of a set of histograms defined with respect to the symmetrized Kullback–Leibler divergence (also called the Jeffreys divergence ) has a closed form using the Lambert W function.

Pooling of tests for infectious diseases

Solving for the optimal group size to pool tests so that at least one individual is infected involves the Lambert W function.

Exact solutions of the Schrödinger equation

The Lambert W function appears in a quantum-mechanical potential, which affords the fifth – next to those of the harmonic oscillator plus centrifugal, the Coulomb plus inverse square, the Morse, and the inverse square root potential – exact solution to the stationary one-dimensional Schrödinger equation in terms of the confluent hypergeometric functions. The potential is given as

A peculiarity of the solution is that each of the two fundamental solutions that compose the general solution of the Schrödinger equation is given by a combination of two confluent hypergeometric functions of an argument proportional to

The Lambert W function also appears in the exact solution for the bound state energy of the one dimensional Schrödinger equation with a Double Delta Potential.

Exact solution of QCD coupling constant

In Quantum chromodynamics, the quantum field theory of the Strong interaction, the coupling constant is computed perturbatively, the order n corresponding to Feynman diagrams including n quantum loops. The first order, n = 1, solution is exact (at that order) and analytical. At higher orders, n > 1, there is no exact and analytical solution and one typically uses an iterative method to furnish an approximate solution. However, for second order, n = 2, the Lambert function provides an exact (if non-analytical) solution.

Exact solutions of the Einstein vacuum equations

In the Schwarzschild metric solution of the Einstein vacuum equations, the W function is needed to go from the Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates to the Schwarzschild coordinates. For this reason, it also appears in the construction of the Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates.

Resonances of the delta-shell potential

The s-wave resonances of the delta-shell potential can be written exactly in terms of the Lambert W function.

Thermodynamic equilibrium

If a reaction involves reactants and products having heat capacities that are constant with temperature then the equilibrium constant K obeys

for some constants a, b, and c. When c (equal to ΔCp/R) is not zero the value or values of T can be found where K equals a given value as follows, where L can be used for ln T.

If a and c have the same sign there will be either two solutions or none (or one if the argument of W is exactly −1/e). (The upper solution may not be relevant.) If they have opposite signs, there will be one solution.

Phase separation of polymer mixtures

In the calculation of the phase diagram of thermodynamically incompatible polymer mixtures according to the Edmond-Ogston model, the solutions for binodal and tie-lines are formulated in terms of Lambert W functions.

Wien's displacement law in a D-dimensional universe

Wien's displacement law is expressed as . With and , where is the spectral energy energy density, one finds , where is the number of degrees of freedom for spatial translation. The solution shows that the spectral energy density is dependent on the dimensionality of the universe.

AdS/CFT correspondence

The classical finite-size corrections to the dispersion relations of giant magnons, single spikes and GKP strings can be expressed in terms of the Lambert W function.

Epidemiology

In the t → ∞ limit of the SIR model, the proportion of susceptible and recovered individuals has a solution in terms of the Lambert W function.

Determination of the time of flight of a projectile

The total time of the journey of a projectile which experiences air resistance proportional to its velocity can be determined in exact form by using the Lambert W function.

Electromagnetic surface wave propagation

The transcendental equation that appears in the determination of the propagation wave number of an electromagnetic axially symmetric surface wave (a low-attenuation single TM01 mode) propagating in a cylindrical metallic wire gives rise to an equation like u ln u = v (where u and v clump together the geometrical and physical factors of the problem), which is solved by the Lambert W function. The first solution to this problem, due to Sommerfeld circa 1898, already contained an iterative method to determine the value of the Lambert W function.

Orthogonal trajectories of real ellipses

The family of ellipses centered at is parameterized by eccentricity . The orthogonal trajectories of this family are given by the differential equation whose general solution is the family .

Generalizations

The standard Lambert W function expresses exact solutions to transcendental algebraic equations (in x) of the form:

| (1) |

where a0, c and r are real constants. The solution is Generalizations of the Lambert W function include:

- An application to general relativity and quantum mechanics (quantum gravity) in lower dimensions, in fact a link (unknown prior to 2007) between these two areas, where the right-hand side of (1) is replaced by a quadratic polynomial in x:

(2) where r1 and r2 are real distinct constants, the roots of the quadratic polynomial. Here, the solution is a function which has a single argument x but the terms like ri and a0 are parameters of that function. In this respect, the generalization resembles the hypergeometric function and the Meijer G function but it belongs to a different class of functions. When r1 = r2, both sides of (2) can be factored and reduced to (1) and thus the solution reduces to that of the standard W function. Equation (2) expresses the equation governing the dilaton field, from which is derived the metric of the R = T or lineal two-body gravity problem in 1 + 1 dimensions (one spatial dimension and one time dimension) for the case of unequal rest masses, as well as the eigenenergies of the quantum-mechanical double-well Dirac delta function model for unequal charges in one dimension.

- Analytical solutions of the eigenenergies of a special case of the quantum mechanical three-body problem, namely the (three-dimensional) hydrogen molecule-ion. Here the right-hand side of (1) is replaced by a ratio of infinite order polynomials in x:

(3) where ri and si are distinct real constants and x is a function of the eigenenergy and the internuclear distance R. Equation (3) with its specialized cases expressed in (1) and (2) is related to a large class of delay differential equations. G. H. Hardy's notion of a "false derivative" provides exact multiple roots to special cases of (3).

Applications of the Lambert W function in fundamental physical problems are not exhausted even for the standard case expressed in (1) as seen recently in the area of atomic, molecular, and optical physics.

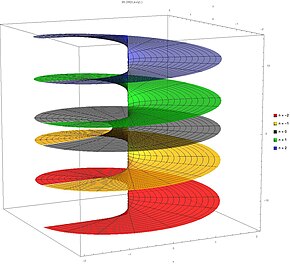

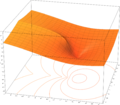

Plots

- Plots of the Lambert W function on the complex plane

-

z = Re(W0(x + iy))

z = Re(W0(x + iy))

-

z = Im(W0(x + iy))

z = Im(W0(x + iy))

-

z = |W0(x + iy)|

z = |W0(x + iy)|

-

Superimposition of the previous three plots

Superimposition of the previous three plots

Numerical evaluation

The W function may be approximated using Newton's method, with successive approximations to w = W(z) (so z = we) being

The W function may also be approximated using Halley's method,

given in Corless et al. to compute W.

For real , it may be approximated by the quadratic-rate recursive formula of R. Iacono and J.P. Boyd:

Lajos Lóczi proves that by using this iteration with an appropriate starting value ,

- For the principal branch

- if :

- if

- if

- For the branch

- if

- if

one can determine the maximum number of iteration steps in advance for any precision:

- if (Theorem 2.4):

- if (Theorem 2.9):

- if

- for the principal branch (Theorem 2.17):

- for the branch (Theorem 2.23):

Toshio Fukushima has presented a fast method for approximating the real valued parts of the principal and secondary branches of the W function without using any iteration. In this method the W function is evaluated as a conditional switch of rational functions on transformed variables:

where x, u, y and v are transformations of z:

- .

Here , , , and are rational functions whose coefficients for different k-values are listed in the referenced paper together with the values that determine the subdomains. With higher degree polynomials in these rational functions the method can approximate the W function more accurately.

For example, when , can be approximated to 24 bits of accuracy on 64-bit floating point values as where x is defined with the transformation above and the coefficients and are given in the table below.

| 0 | −0.9999999403954019 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.0557300521617778 | 2.275906559863465 |

| 2 | 2.1269732491053173 | 1.367597013868904 |

| 3 | 0.8135112367835288 | 0.18615823452831623 |

| 4 | 0.01632488014607016 | 0 |

Fukushima also offers an approximation with 50 bits of accuracy on 64-bit floats that uses 8th- and 7th-degree polynomials.

Software

The Lambert W function is implemented in many programming languages. Some of them are listed below:

| Language | Function name | Required library |

|---|---|---|

| C/C++ | gsl_sf_lambert_W0 and gsl_sf_lambert_Wm1 |

Special functions section of the GNU Scientific Library (GSL) |

lambert_w0, lambert_wm1, lambert_w0_prime, and lambert_wm1_prime |

Boost C++ libraries | |

LambertW |

LambertW-function | |

| GP | lambertw |

|

| Maple | LambertW |

|

| Mathematica | ProductLog (with LambertW as a silent alias) |

|

| Matlab | lambertw |

|

| Maxima | lambert_w |

|

| Octave | lambertw |

specfun

|

| PARI | glambertW, lambertWC, glambertW_i, mplambertW, lambertW |

|

| Perl | LambertW |

ntheory

|

| Python | lambertw |

scipy

|

| R | lambertW0 and lambertWm1 |

lamW

|

| Rust | lambert_w0 and lambert_wm1 |

lambert_w

|

See also

- Wright omega function

- Lambert's trinomial equation

- Lagrange inversion theorem

- Experimental mathematics

- Holstein–Herring method

- R = T model

- Ross' π lemma

Notes

- Lehtonen, Jussi (April 2016), Rees, Mark (ed.), "The Lambert W function in ecological and evolutionary models", Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7 (9): 1110–1118, Bibcode:2016MEcEv...7.1110L, doi:10.1111/2041-210x.12568, S2CID 124111881

- Chow, Timothy Y. (1999), "What is a closed-form number?", American Mathematical Monthly, 106 (5): 440–448, arXiv:math/9805045, doi:10.2307/2589148, JSTOR 2589148, MR 1699262.

- ^ Corless, R. M.; Gonnet, G. H.; Hare, D. E. G.; Jeffrey, D. J.; Knuth, D. E. (1996). "On the LambertW function" (PDF). Advances in Computational Mathematics. 5: 329–359. doi:10.1007/BF02124750. S2CID 29028411.

- Lambert J. H., "Observationes variae in mathesin puram", Acta Helveticae physico-mathematico-anatomico-botanico-medica, Band III, 128–168, 1758.

- Euler, L. "De serie Lambertina Plurimisque eius insignibus proprietatibus". Acta Acad. Scient. Petropol. 2, 29–51, 1783. Reprinted in Euler, L. Opera Omnia, Series Prima, Vol. 6: Commentationes Algebraicae. Leipzig, Germany: Teubner, pp. 350–369, 1921.

- Scott, TC; Babb, JF; Dalgarno, A; Morgan, John D (Aug 15, 1993). "The calculation of exchange forces: General results and specific models". J. Chem. Phys. 99 (4). American Institute of Physics: 2841–2854. Bibcode:1993JChPh..99.2841S. doi:10.1063/1.465193. ISSN 0021-9606.

- Corless, R. M.; Gonnet, G. H.; Hare, D. E. G.; Jeffrey, D. J. (1993). "Lambert's function in Maple". The Maple Technical Newsletter. 9: 12–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.33.2556.

- Mező, István (2022). The Lambert W Function: Its Generalizations and Applications. doi:10.1201/9781003168102. ISBN 9781003168102. S2CID 247491347.

- Bronstein, Manuel; Corless, Robert M.; Davenport, James H.; Jeffrey, D. J. (2008). "Algebraic properties of the Lambert function from a result of Rosenlicht and of Liouville" (PDF). Integral Transforms and Special Functions. 19 (10): 709–712. doi:10.1080/10652460802332342. S2CID 120069437. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-11.

- A. Hoorfar, M. Hassani, Inequalities on the Lambert W Function and Hyperpower Function, JIPAM, Theorem 2.7, page 7, volume 9, issue 2, article 51. 2008.

- Chatzigeorgiou, I. (2013). "Bounds on the Lambert function and their Application to the Outage Analysis of User Cooperation". IEEE Communications Letters. 17 (8): 1505–1508. arXiv:1601.04895. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2013.070113.130972. S2CID 10062685.

- ^ Iacono, Roberto; Boyd, John P. (2017-12-01). "New approximations to the principal real-valued branch of the Lambert W-function". Advances in Computational Mathematics. 43 (6): 1403–1436. doi:10.1007/s10444-017-9530-3. ISSN 1572-9044. S2CID 254184098.

- "Lambert function: Identities (formula 01.31.17.0001)".

- "Lambert W-Function".

- https://isa-afp.org/entries/Lambert_W.html Note: although one of the assumptions of the relevant lemma states that x must be > 1/e, inspection of said lemma reveals that this assumption is unused. The lower bound is in fact x > 0. The reason for the branch switch at e is simple: for x > 1 there are always two solutions, −ln x and another one that you'd get from the x on the other side of e that would feed the same value to W; these must crossover at x = e: Wn cannot distinguish a value of ln x/x from an x < e from the same value from the other x > e, so it cannot flip the order of its return values.

- Finch, S. R. (2003). Mathematical constants. Cambridge University Press. p. 450.

- Kalugin, German A.; Jeffrey, David J.; Corless, Robert M. (2012). "Bernstein, Pick, Poisson and related integral expressions for Lambert W" (PDF). Integral Transforms and Special Functions. 23 (11): 817–829. doi:10.1080/10652469.2011.640327. MR 2989751. See Theorem 3.4, p. 821 of published version (p. 5 of preprint).

- Dubinov, A. E.; Dubinova, I. D.; Saǐkov, S. K. (2006). The Lambert W Function and Its Applications to Mathematical Problems of Physics (in Russian). RFNC-VNIIEF. p. 53.

- Robert M., Corless; David J., Jeffrey; Donald E., Knuth (1997). "A sequence of series for the Lambert W function". Proceedings of the 1997 international symposium on Symbolic and algebraic computation - ISSAC '97. pp. 197–204. doi:10.1145/258726.258783. ISBN 978-0897918756. S2CID 6274712.

- "The Lambert W Function". Ontario Research Centre for Computer Algebra.

- More, A. A. (2006). "Analytical solutions for the Colebrook and White equation and for pressure drop in ideal gas flow in pipes". Chemical Engineering Science. 61 (16): 5515–5519. Bibcode:2006ChEnS..61.5515M. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2006.04.003.

- Pellegrini, C. C.; Zappi, G. A.; Vilalta-Alonso, G. (2022-05-12). "An Analytical Solution for the Time-Dependent Flow in Simple Branch Hydraulic Systems with Centrifugal Pumps". Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering. 47 (12): 16273–16287. doi:10.1007/s13369-022-06864-9. ISSN 2193-567X. S2CID 248762601.

- Sotero, Roberto C.; Iturria-Medina, Yasser (2011). "From Blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signals to brain temperature maps". Bull Math Biol (Submitted manuscript). 73 (11): 2731–47. doi:10.1007/s11538-011-9645-5. PMID 21409512. S2CID 12080132.

- Braun, Artur; Wokaun, Alexander; Hermanns, Heinz-Guenter (2003). "Analytical Solution to a Growth Problem with Two Moving Boundaries". Appl Math Model. 27 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1016/S0307-904X(02)00085-9.

- Braun, Artur; Baertsch, Martin; Schnyder, Bernhard; Koetz, Ruediger (2000). "A Model for the film growth in samples with two moving boundaries – An Application and Extension of the Unreacted-Core Model". Chem Eng Sci. 55 (22): 5273–5282. doi:10.1016/S0009-2509(00)00143-3.

- Asadian, M; Saeedi, H; Yadegari, M; Shojaee, M (June 2014). "Determinations of equilibrium segregation, effective segregation and diffusion coefficients for Nd+3 doped in molten YAG". Journal of Crystal Growth. 396 (15): 61–65. Bibcode:2014JCrGr.396...61A. doi:10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2014.03.028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2014.03.028

- Asadian, M; Zabihi, F; Saeedi, H (March 2024). "Segregation and constitutional supercooling in Nd:YAG Czochralski crystal growth". Journal of Crystal Growth. 630: 127605. Bibcode:2024JCrGr.63027605A. doi:10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2024.127605. S2CID 267414096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2024.127605

- Braun, Artur; Briggs, Keith M.; Boeni, Peter (2003). "Analytical solution to Matthews' and Blakeslee's critical dislocation formation thickness of epitaxially grown thin films". J Cryst Growth. 241 (1–2): 231–234. Bibcode:2002JCrGr.241..231B. doi:10.1016/S0022-0248(02)00941-7.

- Colla, Pietro (2014). "A New Analytical Method for the Motion of a Two-Phase Interface in a Tilted Porous Medium". PROCEEDINGS, Thirty-Eighth Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford University. SGP-TR-202.()

- D. J. Jeffrey and J. E. Jankowski, "Branch differences and Lambert W"

- Flavia-Corina Mitroi-Symeonidis; Ion Anghel; Shigeru Furuichi (2019). "Encodings for the calculation of the permutation hypoentropy and their applications on full-scale compartment fire data". Acta Technica Napocensis. 62, IV: 607–616.

- F. Nielsen, "Jeffreys Centroids: A Closed-Form Expression for Positive Histograms and a Guaranteed Tight Approximation for Frequency Histograms"

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.03051 J. Batson et al., "A COMPARISON OF GROUP TESTING ARCHITECTURES FOR COVID-19 TESTING".

- A.Z. Broder, "A Note on Double Pooling Tests".

- Rudolf Hanel, Stefan Thurner (2020). "Boosting test-efficiency by pooled testing for SARS-CoV-2—Formula for optimal pool size". PLOS ONE. 15, 11 (11): e0240652. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1540652H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240652. PMC 7641378. PMID 33147228.

- A.M. Ishkhanyan, "The Lambert W barrier – an exactly solvable confluent hypergeometric potential".

- ^ Deur, Alexandre; Brodsky, Stanley J.; De Téramond, Guy F. (2016). "The QCD running coupling". Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 90: 1–74. arXiv:1604.08082. Bibcode:2016PrPNP..90....1D. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2016.04.003. S2CID 118854278.

- de la Madrid, R. (2017). "Numerical calculation of the decay widths, the decay constants, and the decay energy spectra of the resonances of the delta-shell potential". Nucl. Phys. A. 962: 24–45. arXiv:1704.00047. Bibcode:2017NuPhA.962...24D. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2017.03.006. S2CID 119218907.

- Bot, A.; Dewi, B.P.C.; Venema, P. (2021). "Phase-separating binary polymer mixtures: the degeneracy of the virial coefficients and their extraction from phase diagrams". ACS Omega. 6 (11): 7862–7878. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c00450. PMC 7992149. PMID 33778298.

- Cardoso, T. R.; de Castro, A. S. (2005). "The blackbody radiation in a D-dimensional universe". Rev. Bras. Ens. Fis. 27 (4): 559–563. doi:10.1590/S1806-11172005000400007. hdl:11449/211894.

- Floratos, Emmanuel; Georgiou, George; Linardopoulos, Georgios (2014). "Large-Spin Expansions of GKP Strings". JHEP. 2014 (3): 0180. arXiv:1311.5800. Bibcode:2014JHEP...03..018F. doi:10.1007/JHEP03(2014)018. S2CID 53355961.

- Floratos, Emmanuel; Linardopoulos, Georgios (2015). "Large-Spin and Large-Winding Expansions of Giant Magnons and Single Spikes". Nucl. Phys. B. 897: 229–275. arXiv:1406.0796. Bibcode:2015NuPhB.897..229F. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2015.05.021. S2CID 118526569.

- Wolfram Research, Inc. "Mathematica, Version 12.1". Champaign IL, 2020.

- Mendonça, J. R. G. (2019). "Electromagnetic surface wave propagation in a metallic wire and the Lambert W function". American Journal of Physics. 87 (6): 476–484. arXiv:1812.07456. Bibcode:2019AmJPh..87..476M. doi:10.1119/1.5100943. S2CID 119661071.

- Scott, T. C.; Mann, R. B.; Martinez Ii, Roberto E. (2006). "General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics: Towards a Generalization of the Lambert W Function". AAECC (Applicable Algebra in Engineering, Communication and Computing). 17 (1): 41–47. arXiv:math-ph/0607011. Bibcode:2006math.ph...7011S. doi:10.1007/s00200-006-0196-1. S2CID 14664985.

- Scott, T. C.; Fee, G.; Grotendorst, J. (2013). "Asymptotic series of Generalized Lambert W Function". SIGSAM (ACM Special Interest Group in Symbolic and Algebraic Manipulation). 47 (185): 75–83. doi:10.1145/2576802.2576804. S2CID 15370297.

- Scott, T. C.; Fee, G.; Grotendorst, J.; Zhang, W.Z. (2014). "Numerics of the Generalized Lambert W Function". SIGSAM. 48 (1/2): 42–56. doi:10.1145/2644288.2644298. S2CID 15776321.

- Farrugia, P. S.; Mann, R. B.; Scott, T. C. (2007). "N-body Gravity and the Schrödinger Equation". Class. Quantum Grav. 24 (18): 4647–4659. arXiv:gr-qc/0611144. Bibcode:2007CQGra..24.4647F. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/24/18/006. S2CID 119365501.

- Scott, T. C.; Aubert-Frécon, M.; Grotendorst, J. (2006). "New Approach for the Electronic Energies of the Hydrogen Molecular Ion". Chem. Phys. 324 (2–3): 323–338. arXiv:physics/0607081. Bibcode:2006CP....324..323S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.261.9067. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2005.10.031. S2CID 623114.

- Maignan, Aude; Scott, T. C. (2016). "Fleshing out the Generalized Lambert W Function". SIGSAM. 50 (2): 45–60. doi:10.1145/2992274.2992275. S2CID 53222884.

- Scott, T. C.; Lüchow, A.; Bressanini, D.; Morgan, J. D. III (2007). "The Nodal Surfaces of Helium Atom Eigenfunctions" (PDF). Phys. Rev. A. 75 (6): 060101. Bibcode:2007PhRvA..75f0101S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.75.060101. hdl:11383/1679348. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22.

- Lóczi, Lajos (2022-11-15). "Guaranteed- and high-precision evaluation of the Lambert W function". Applied Mathematics and Computation. 433: 127406. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2022.127406. hdl:10831/89771. ISSN 0096-3003.

- Fukushima, Toshio (2020-11-25). "Precise and fast computation of Lambert W function by piecewise minimax rational function approximation with variable transformation". doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.30264.37128.

- "Lambert W Functions - GNU Scientific Library (GSL)".

- "Lambert W function - Boost libraries".

- Mező, István (2017-12-05), LambertW-function, retrieved 2024-12-13

- "LambertW - Maple Help".

- ProductLog - Wolfram Language Reference

- lambertw – MATLAB

- Maxima, a Computer Algebra System

- "lambertw - specfun on Octave-Forge". Retrieved 2024-09-12.

- ntheory - MetaCPAN

- "Scipy.special.lambertw — SciPy v0.16.1 Reference Guide".

- Adler, Avraham (2017-04-24), lamW: Lambert W Function, retrieved 2017-12-19

- Sörngård, Johanna (2024-07-28), lambert_w, retrieved 2024-09-11

References

- Corless, R.; Gonnet, G.; Hare, D.; Jeffrey, D.; Knuth, Donald (1996). "On the Lambert W function" (PDF). Advances in Computational Mathematics. 5: 329–359. doi:10.1007/BF02124750. ISSN 1019-7168. S2CID 29028411. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-14. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- Chapeau-Blondeau, F.; Monir, A. (2002). "Evaluation of the Lambert W Function and Application to Generation of Generalized Gaussian Noise With Exponent 1/2" (PDF). IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 50 (9). doi:10.1109/TSP.2002.801912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2004-03-10.

- Francis; et al. (2000). "Quantitative General Theory for Periodic Breathing". Circulation. 102 (18): 2214–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.505.7194. doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2214. PMID 11056095. S2CID 14410926. (Lambert function is used to solve delay-differential dynamics in human disease.)

- Hayes, B. (2005). "Why W?" (PDF). American Scientist. 93 (2): 104–108. doi:10.1511/2005.2.104. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- Roy, R.; Olver, F. W. J. (2010), "Lambert W function", in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W. (eds.), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, MR 2723248.

- Stewart, Seán M. (2005). "A New Elementary Function for Our Curricula?" (PDF). Australian Senior Mathematics Journal. 19 (2): 8–26. ISSN 0819-4564. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

- Veberic, D., "Having Fun with Lambert W(x) Function" arXiv:1003.1628 (2010); Veberic, D. (2012). "Lambert W function for applications in physics". Computer Physics Communications. 183 (12): 2622–2628. arXiv:1209.0735. Bibcode:2012CoPhC.183.2622V. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2012.07.008. S2CID 315088.

- Chatzigeorgiou, I. (2013). "Bounds on the Lambert function and their Application to the Outage Analysis of User Cooperation". IEEE Communications Letters. 17 (8): 1505–1508. arXiv:1601.04895. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2013.070113.130972. S2CID 10062685.

External links

- National Institute of Science and Technology Digital Library – Lambert W

- MathWorld – Lambert W-Function

- Computing the Lambert W function

- Corless et al. Notes about Lambert W research

- GPL C++ implementation with Halley's and Fritsch's iteration.

- Special Functions of the GNU Scientific Library – GSL

. Taking limits, he derived the equation

. Taking limits, he derived the equation

and obtained a convergent series solution for the resulting equation, expressing

and obtained a convergent series solution for the resulting equation, expressing  in terms of

in terms of  .

.

function provides an exact solution to the quantum-mechanical

function provides an exact solution to the quantum-mechanical  is true.

is true.  implies that there exists an

implies that there exists an  such that

such that  , where

, where  . The value of the integer

. The value of the integer  is at the branch cut of

is at the branch cut of  , which means that

, which means that  where it is

where it is  .

.

, where

, where  are real, and expressing

are real, and expressing  in polar coordinates, it is seen that

in polar coordinates, it is seen that

, the branch cut for

, the branch cut for

is the real axis with

is the real axis with  , so that the inequality becomes

, so that the inequality becomes

and

and  , with equality only for

, with equality only for  .

The bound allows many other bounds to be made, such as taking

.

The bound allows many other bounds to be made, such as taking  which gives the bound

which gives the bound

(the

(the

and

and

where

where  is the initial flow rate and

is the initial flow rate and  is time.

is time.

, and solute concentration in the melt,

, and solute concentration in the melt,  , from the

, from the

is computed perturbatively, the order n corresponding to

is computed perturbatively, the order n corresponding to

. With

. With  and

and  , where

, where  is the spectral energy energy density, one finds

is the spectral energy energy density, one finds  , where

, where  is the number of degrees of freedom for spatial translation. The solution

is the number of degrees of freedom for spatial translation. The solution  shows that the spectral energy density is dependent on the dimensionality of the universe.

shows that the spectral energy density is dependent on the dimensionality of the universe.

centered at

centered at  is parameterized by eccentricity

is parameterized by eccentricity  . The orthogonal trajectories of this family are given by the differential equation

. The orthogonal trajectories of this family are given by the differential equation  whose general solution is the family

whose general solution is the family

.

.

Generalizations of the Lambert W function include:

Generalizations of the Lambert W function include:

,

,

:

:

![{\displaystyle x\in (-1/e,-1/4]:}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/24b94a22ce7703c01fad21e3dc02064c914fb7aa)

(Theorem 2.9):

(Theorem 2.9):

(Theorem 2.17):

(Theorem 2.17):

(Theorem 2.23):

(Theorem 2.23):

where x, u, y and v are transformations of z:

where x, u, y and v are transformations of z:

.

. ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are rational functions whose coefficients for different k-values are listed in the referenced paper together with the

are rational functions whose coefficients for different k-values are listed in the referenced paper together with the  values that determine the subdomains. With higher degree polynomials in these rational functions the method can approximate the W function more accurately.

values that determine the subdomains. With higher degree polynomials in these rational functions the method can approximate the W function more accurately.

,

,  can be approximated to 24 bits of accuracy on 64-bit floating point values as

can be approximated to 24 bits of accuracy on 64-bit floating point values as  where x is defined with the transformation above and the coefficients

where x is defined with the transformation above and the coefficients  and

and