| Revision as of 20:33, 9 April 2012 edit199.58.164.113 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:57, 9 April 2012 edit undoMastCell (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators43,155 edits rv unexplained reinsertion; discussion ongoing on talk pageNext edit → | ||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

| The azido group increases the ] nature of AZT, allowing it to cross infected ]s easily by ] and thereby also to cross the ]. Cellular enzymes convert AZT into the effective 5'-triphosphate form. Studies have proven that the termination of HIV's forming DNA chains is the specific factor in the inhibitory effect. | The azido group increases the ] nature of AZT, allowing it to cross infected ]s easily by ] and thereby also to cross the ]. Cellular enzymes convert AZT into the effective 5'-triphosphate form. Studies have proven that the termination of HIV's forming DNA chains is the specific factor in the inhibitory effect. | ||

| ⚫ | At very high doses, AZT's triphosphate form may also inhibit ] used by human cells to undergo ], but regardless of dosage AZT has an approximately 100-fold greater affinity for HIV's reverse transcriptase.<ref name=FurmanPNAS>{{cite journal | author=Furman P, Fyfe J, St Clair M, Weinhold K, Rideout J, Freeman G, Lehrman S, Bolognesi D, Broder S, Mitsuya H | title=Phosphorylation of 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine and selective interaction of the 5'-triphosphate with human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase | journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci USA | volume=83 | issue=21 | pages=8333–7 | year=1986 | pmid=2430286 | doi=10.1073/pnas.83.21.8333 | pmc=386922}}</ref> The selectivity has been proven to be due to the cell's ability to quickly repair its own DNA chain if it is broken by AZT during its formation, whereas the HIV virus lacks that ability.<ref>Induction of Endogenous Virus and of Thymidline Kinase. http://www.pnas.org/content/71/12/4980.full.pdf</ref> Thus AZT inhibits HIV replication without affecting the function of uninfected cells.<ref name=MitsuyaPNAS/> At sufficiently high dosages, the cellular DNA polymerase used by ] to replicate may be somewhat more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of AZT, accounting for its potentially toxic but reversible effects on ] and ]s, causing ].<!-- | ||

| At very high doses, AZT's triphosphate form may also inhibit ] used by human cells to undergo ], and AZT has been ] as possibly ] to humans by the ]. | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| --><ref>{{cite journal | author=Collins M, Sondel N, Cesar D, Hellerstein M | title=Effect of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on mitochondrial DNA synthesis in rats and humans | journal=J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr | volume=37 | issue=1 | pages=1132–9 | year=2004 | pmid=15319672 | doi=10.1097/01.qai.0000131585.77530.64}}</ref><!-- | --><ref>{{cite journal | author=Collins M, Sondel N, Cesar D, Hellerstein M | title=Effect of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on mitochondrial DNA synthesis in rats and humans | journal=J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr | volume=37 | issue=1 | pages=1132–9 | year=2004 | pmid=15319672 | doi=10.1097/01.qai.0000131585.77530.64}}</ref><!-- | ||

| --><ref>{{cite journal | author=Parker W, White E, Shaddix S, Ross L, Buckheit R, Germany J, Secrist J, Vince R, Shannon W | title=Mechanism of inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and human DNA polymerases alpha, beta, and gamma by the 5'-triphosphates of carbovir, 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, 2',3'-dideoxyguanosine and 3'-deoxythymidine. A novel RNA template for the evaluation of antiretroviral drugs | journal=J Biol Chem | volume=266 | issue=3 | pages=1754–62 | year=1991 | pmid=1703154}}</ref><!-- | --><ref>{{cite journal | author=Parker W, White E, Shaddix S, Ross L, Buckheit R, Germany J, Secrist J, Vince R, Shannon W | title=Mechanism of inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and human DNA polymerases alpha, beta, and gamma by the 5'-triphosphates of carbovir, 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, 2',3'-dideoxyguanosine and 3'-deoxythymidine. A novel RNA template for the evaluation of antiretroviral drugs | journal=J Biol Chem | volume=266 | issue=3 | pages=1754–62 | year=1991 | pmid=1703154}}</ref><!-- | ||

| Line 127: | Line 126: | ||

| --><ref>{{cite journal | author=Balzarini J, Naesens L, Aquaro S, Knispel T, Perno C, De Clercq E, Meier C | title=Intracellular metabolism of CycloSaligenyl 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine monophosphate, a prodrug of 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine) | journal=Mol Pharmacol | volume=56 | issue=6 | pages=1354–61 | date=1 December 1999| pmid=10570065 | url=http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/56/6/1354 }}</ref><!-- | --><ref>{{cite journal | author=Balzarini J, Naesens L, Aquaro S, Knispel T, Perno C, De Clercq E, Meier C | title=Intracellular metabolism of CycloSaligenyl 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine monophosphate, a prodrug of 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine) | journal=Mol Pharmacol | volume=56 | issue=6 | pages=1354–61 | date=1 December 1999| pmid=10570065 | url=http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/56/6/1354 }}</ref><!-- | ||

| --><ref name="Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Myers C, Broder S 1989 726–38"/> | --><ref name="Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Myers C, Broder S 1989 726–38"/> | ||

| AZT's therapeutic mechanism is unrelated to chemotherapy.<ref>MedicineNet.com. Chemotherapy. http://www.medicinenet.com/chemotherapy/article.htm</ref> | |||

| ==Patent issues== | ==Patent issues== | ||

Revision as of 20:57, 9 April 2012

"AZT" redirects here. For other uses, see AZT (disambiguation). Pharmaceutical compound | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | near complete absorption, following first-pass metabolism systemic availability 65% (range 52 to 75%) |

| Protein binding | 30 to 38% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 0.5 to 3 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.152.492 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H13N5O4 |

| Molar mass | 267.242 g/mol g·mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (what is this?) (verify) | |

Zidovudine (INN) or azidothymidine (AZT) (also called ZDV) is a nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), a type of antiretroviral drug used for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. It is an analog of thymidine.

AZT was the first approved treatment for HIV, sold under the names Retrovir and Retrovis. AZT use was a major breakthrough in AIDS therapy in the 1990s that significantly altered the course of the illness and helped destroy the notion that HIV/AIDS was a death sentence. AZT slows HIV spread significantly, but may not always stop it entirely. This allows HIV to become AZT-resistant over time, and for this reason AZT is usually used in conjunction with other NRTIs and anti-viral drugs. In this form, AZT is used as an ingredient in Combivir and Trizivir, among others. Zidovudine is included in the World Health Organization's "Essential Drugs List", which is a list of minimum medical needs for a basic health care system.

History

Development

In the 1970s the theory that most cancers were caused by environmental retroviruses gained currency. It had recently become known, due to the work of Howard Temin, that most avian cancers were caused by retroviruses, but corresponding human viruses were not known.

In parallel work, compounds that interfered with the synthesis of nucleic acids had been synthesized as possible antibacterial, and then anticancer agents, for example in the laboratory of George Hitchings and Gertrude Elion, leading to the successful use of 6-mercaptopurine to treat leukemia .

Jerome Horwitz of the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute and Wayne State University School of Medicine first synthesized AZT in 1964 under a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant. Development was shelved after it proved insufficiently effective against tumors in mice. In 1974, Wolfram Ostertag of the Max Planck Institute in Germany reported that AZT was active against Friend murine leukaemia virus, a retrovirus, in a mouse culture system.

The anti-retroviral approach to develop a "silver bullet" cancer cure ultimately failed. Contrary to early belief, today it is estimated that viruses account for only 10 to 20% of human cancers. However, these efforts advanced the knowledge of cancer considerably, and led to rapid development of many anti-retroviral drugs, which would later prove useful. Zidovudine (AZT) was approved for marketing by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on March 20, 1987.

Chemistry

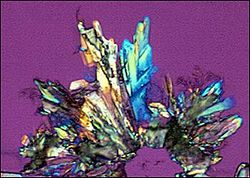

AZT crystallizes in a monoclinic structure, forming a hydrogen bonded network of base-paired dimers; its crystal structure was reported in 1988.

HIV Treatment

In 1984, shortly after the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) had been confirmed as the cause of AIDS, scientists at the Burroughs-Wellcome Company (now GlaxoSmithKline) began searching for compounds to treat the disease. Burroughs-Wellcome had expertise in viral diseases, led by researchers including Gertrude Elion, David Barry, Paul (Chip) McGuirt Jr., Philip Furman, Martha St. Clair, Janet Rideout, Sandra Lehrman and others. Their research efforts focused on the viral enzyme reverse transcriptase. Reverse transcriptase is an enzyme that retroviruses, including HIV, utilize to replicate themselves. Scientists at Burroughs-Wellcome began to identify and synthesize compounds and developed a screen to test for activity against murine (mouse) retroviruses. One compound, coded "BW A509U", was tested and demonstrated potent activity against mouse viruses.

At the same time, Samuel Broder, Hiroaki Mitsuya, and Robert Yarchoan of the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) had initiated an independent program to develop therapies for HIV/AIDS. The Burroughs-Wellcome scientists were not working directly with HIV, so the two groups began a collaboration. In February 1985, the NCI scientists proved that BW A509U, one of 11 compounds sent to them by Burroughs-Wellcome, had potent activity against HIV in the test tube. Several months later, Broder, Mitsuya, and Yarchoan started the initial phase 1 clinical trial of AZT at the NCI, in collaboration with scientists from Burroughs-Wellcome and Duke University. This trial proved that the drug can be safely administered to patients with HIV and that it increases their CD4 counts.

A rigorously maintained double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of AZT was subsequently conducted by Burroughs-Wellcome. The study, which was commended for its standards, proved that AZT safely prolongs the lives of patients with HIV. Burroughs-Wellcome filed for a patent for AZT in 1985. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug (via the then-new FDA accelerated approval system) for use against HIV, AIDS, and AIDS Related Complex (ARC, a now-defunct medical term for pre-AIDS illness) on March 20, 1987. The time between the first demonstration that AZT was active against HIV in the laboratory and its approval was 25 months, one of the shortest periods of drug development in recent history.

AZT was subsequently approved unanimously for children in 1990. AZT was initially administered in somewhat higher dosages than today, typically 400 mg every four hours, day and night. The paucity of alternatives for treating HIV/AIDS at that time unambiguously affirmed the risk/benefit ratio, with inevitable slow and painful death from HIV infection outweighing the potential for temporary discomfort from the drug's initial side-effects, one of which was anemia, a common but transient complaint for some patients in early trials.

Current treatment regimens involve relatively lower dosages (e.g., 300 mg) of AZT taken twice a day, almost always as part of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), in which AZT is combined with other drugs (known as a "triple cocktail") in order to prevent the mutation of HIV into an AZT-resistant form.

HIV Prophylaxis

AZT is used as post-exposure prophylaxis in combination with other antiretroviral medications, substantially reducing the risk of HIV infection following a significant exposure to the virus (such as a needle-stick injury involving blood or body fluids from an individual known or thought to be infected with HIV).

AZT is part of the clinical pathway for both pre-exposure prophylaxis and post-exposure treatment of mother-to-child transmission of HIV during pregnancy, labor, and delivery and has been proven to be integral to healthy perinatal and neonatal development. Without AZT, as many as 25% of infants whose mothers are infected with HIV will become infected. AZT has been shown to reduce this risk to as little as 8% when given in a three-part regimen during pregnancy, delivery and to the infant for 6 weeks after birth. Consistent and proactive precautionary measures, such as the rigorous use of antiretroviral medications, cesarean section, rubber gloves, disposable diapers, and avoidance of kissing and breast feeding will further reduce mother-child transmission of HIV to as little as 1–2%. During the period from 1994 to 1999 when this was the primary form of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission, AZT prophylaxis prevented more than 1000 parental and infant deaths from AIDS. AZT is also considered the most promising prophylaxis protocol for sexually active HIV-negative women.

Side effects

Early long-term high-dose therapy with AZT was initially associated with some potentially quantifiable side effects, including anemia, neutropenia, hepatotoxicity, cardiomyopathy, and myopathy. All of these conditions were found to be reversible upon cessation of AZT treatment. They have been attributed to several possible causes, including depletion of mitochondrial DNA, sensitivity of the γ-DNA polymerase in the cell mitochondria, the depletion of thymidine triphosphate, oxidative stress, reduction of intracellular L-carnitine or apoptosis of the muscle cells. Anemia due to AZT was successfully treated using erythropoietin to stimulate red blood cell production. Drugs that inhibit hepatic glucuronidation, such as indomethacin, acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) and trimethoprim, decreased the elimination rate and increased the strength of the medication. Minor side effects included upset stomach and acid reflux (heartburn), headache, reduction in body fat, light sleeping, and occasional loss of appetite; while less common complaints included discoloration of fingernails and toenails, mood swings, occasional tingling or numbness of the hands or feet, and topical skin discoloration. Serious allergic reactions were rare.

Today, persistent side-effects have largely been eliminated. No long-term toxicities or genetic impacts of therapeutic AZT usage at any dosage have been demonstrated in thousands of patients treated with HIV. No mortality as a direct or indirect result of AZT use during human testing and prescribed use has been documented.

Viral resistance

Even at very high doses, AZT lacks the underlying toxicity to destroy all of the HIV infection, and may only slow the replication of the virus and the progression of the disease. During prolonged AZT treatment, HIV has the potential to gain an increased resistance to AZT by mutation of its reverse transcriptase. To slow the development of resistance, physicians generally recommend that AZT be given in combination with another reverse transcriptase inhibitor and an antiretroviral from another group, such as a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; this type of therapy is known as HAART (Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy). AZT has been shown to work additively or synergistically with many antiviral agents such as acyclovir and interferon; however, ribavirin decreases the antiviral effect of AZT.

Mechanism of action

AZT works by selectively inhibiting HIV's reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that the virus uses to make a DNA copy of its RNA. Reverse transcription is necessary for production of HIV's double-stranded DNA, which would be subsequently integrated into the genetic material of the infected cell (where it is called a provirus).

The azido group increases the lipophilic nature of AZT, allowing it to cross infected cell membranes easily by diffusion and thereby also to cross the blood-brain barrier. Cellular enzymes convert AZT into the effective 5'-triphosphate form. Studies have proven that the termination of HIV's forming DNA chains is the specific factor in the inhibitory effect.

At very high doses, AZT's triphosphate form may also inhibit DNA polymerase used by human cells to undergo cell division, but regardless of dosage AZT has an approximately 100-fold greater affinity for HIV's reverse transcriptase. The selectivity has been proven to be due to the cell's ability to quickly repair its own DNA chain if it is broken by AZT during its formation, whereas the HIV virus lacks that ability. Thus AZT inhibits HIV replication without affecting the function of uninfected cells. At sufficiently high dosages, the cellular DNA polymerase used by mitochondria to replicate may be somewhat more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of AZT, accounting for its potentially toxic but reversible effects on cardiac and skeletal muscles, causing myositis.

AZT's therapeutic mechanism is unrelated to chemotherapy.

Patent issues

The patents on AZT have been the target of some controversy. In 1991, Public Citizen filed a lawsuit claiming that the patents were invalid. Subsequently, Barr Laboraties and Novopharm Ltd. also challenged the patent, in part based on the assertion that NCI scientists Samuel Broder, Hiroaki Mitsuya, and Robert Yarchoan should have been named as inventors, and those two companies applied to the FDA to sell AZT as a generic drug. In response, Burroughs Wellcome Co. filed a lawsuit against the two companies. The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in 1992 in favor of Burroughs Wellcome, claiming that even though they had never tested it against HIV, they had conceived of it working before they sent it to the NCI scientists. In 2002, another lawsuit was filed over the patent by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation.

However, the patent expired in 2005 (placing AZT in the public domain), allowing other drug companies to manufacture and market generic AZT without having to pay GlaxoSmithKline any royalties. The U.S. FDA has since approved four generic forms of AZT for sale in the U.S.

In November 2009 GlaxoSmithKline formed a joint venture with Pfizer which combined the two companies' HIV assets in one company called ViiV Healthcare. This included the rights to Zidovudine.

References

- "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- "Zidovudine". PubChem Public Chemical Database. NCBI. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- AIDS therapy. First tentative signs of therapeutic promise. Wright, K. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3463865

- Zidovudine resistant HIV. D.J. Jeffries. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2500164

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Link text, additional text. Cite error: The named reference "test" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20018391, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20018391instead. - Horwitz, JP (1964). "The monomesylates of 1-(2-deoxy-bd-lyxofuranosyl) thymines". Org. Chem. Ser. Monogr. 29 (7): 2076–9. doi:10.1021/jo01030a546.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Detours V; Henry D (writers/directors) (2002). I am alive today (history of an AIDS drug) (Film). ADR Productions/Good & Bad News.

- "A Failure Led to Drug Against AIDS". The New York Times. 1986-09-20. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 4531031 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 4531031instead. - ^ Cimons, Marlene (21 March 1987). "U.S. Approves Sale of AZT to AIDS Patients". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- Dyer I, Low JN, Tollin P, Wilson HR, Howie RA (1988). "Structure of 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, AZT". Acta Crystallogr C. 44 (4): 767–9. PMID 3271074.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitsuya H, Weinhold K, Furman P, St Clair M, Lehrman S, Gallo R, Bolognesi D, Barry D, Broder S (1985). "3'-Azido-3'-deoxythymidine (BW A509U): an antiviral agent that inhibits the infectivity and cytopathic effect of human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus in vitro". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 82 (20): 7096–100. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.20.7096. PMC 391317. PMID 2413459.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Myers C, Broder S (1989). "Clinical pharmacology of 3'-azido-2',3'-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine) and related dideoxynucleosides". N Engl J Med. 321 (11): 726–38. doi:10.1056/NEJM198909143211106. PMID 2671731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yarchoan R, Klecker R, Weinhold K, Markham P, Lyerly H, Durack D, Gelmann E, Lehrman S, Blum R, Barry D (1986). "Administration of 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, an inhibitor of HTLV-III/LAV replication, to patients with AIDS or AIDS-related complex". Lancet. 1 (8481): 575–80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92808-4. PMID 2869302.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Harvard Business Review. Burroughs Wellcome and AZT.http://hbr.org/product/burroughs-wellcome-and-azt-c/an/793115-PDF-ENG

- Fischl MA; Richman DD; Grieco MH; Gottlieb MS; Volberding PA; Laskin OL; Leedom JM; Groopman JE; Mildvan D (1987). "The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". N Engl J Med. 317 (4): 185–91. doi:10.1056/NEJM198707233170401. PMID 3299089.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=10(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - AZT Approved for AIDS Children. http://articles.latimes.com/1990-05-03/news/mn-603_1_azt-approved-for-aids-children

- De Clercq E (1994). "HIV resistance to reverse transcriptase inhibitors". Biochem Pharmacol. 47 (2): 155–69. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(94)90001-9. PMID 7508227.

- Yarchoan R, Mitsuya H, Broder S (1988). "AIDS therapies". Sci Am. 259 (4): 110–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1088-110. PMID 3072667.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HIV". Retrieved 2006-03-29.

- "Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-03-29.

- PLOS Hub. Clinical Trials. http://clinicaltrials.ploshubs.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pctr.0020011

- CIDRZ. Prevention of Mother to Child AIDS Transmission (PMTCT). http://www.cidrz.org/pmtct

- Connor E, Sperling R, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O'Sullivan M, VanDyke R, Bey M, Shearer W, Jacobson R (1994). "Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group". N Engl J Med. 331 (18): 1173–80. doi:10.1056/NEJM199411033311801. PMID 7935654.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Walensky RP; Paltiel AD; Losina E; et al. (2006). "The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States". J. Infect. Dis. 194 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1086/505147. PMID 16741877.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); no-break space character in|first4=at position 7 (help); no-break space character in|first5=at position 6 (help); no-break space character in|first6=at position 5 (help); no-break space character in|first7=at position 7 (help); no-break space character in|first8=at position 8 (help) - Retrovirilogy. Pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV: It is time. http://www.retrovirology.com/content/1/1/16

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20544523, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 20544523instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18504416 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 18504416instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9402140, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=9402140instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12524467 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12524467instead. - "ZIDOVUDINE (AZT) - ORAL (Retrovir) side effects, medical uses, and drug interactions". MedicineNet.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accesasdate=ignored (help) - "zidovudine, Retrovir". Medicinenet.com. 2010-08-12. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- Side Effects. NAM Aidsmap. http://www.aidsmap.com/Side-effects/page/1730907/

- Magic Johnson combats AIDS misperceptions. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-11-30-magic-aids_x.htm

- Zidovudine. EC.Europa.eu. Health Documents. http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2011/2011022894311/anx_94311_en.pdf

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2186629, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2186629instead. - Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15855480, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15855480instead. - Mitsuya H, Yarchoan R, Broder S (1990). "Molecular targets for AIDS therapy". Science. 249 (4976): 1533–44. doi:10.1126/science.1699273. PMID 1699273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Furman P, Fyfe J, St Clair M, Weinhold K, Rideout J, Freeman G, Lehrman S, Bolognesi D, Broder S, Mitsuya H (1986). "Phosphorylation of 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine and selective interaction of the 5'-triphosphate with human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 83 (21): 8333–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.21.8333. PMC 386922. PMID 2430286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Induction of Endogenous Virus and of Thymidline Kinase. http://www.pnas.org/content/71/12/4980.full.pdf

- Collins M, Sondel N, Cesar D, Hellerstein M (2004). "Effect of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on mitochondrial DNA synthesis in rats and humans". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 37 (1): 1132–9. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000131585.77530.64. PMID 15319672.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Parker W, White E, Shaddix S, Ross L, Buckheit R, Germany J, Secrist J, Vince R, Shannon W (1991). "Mechanism of inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and human DNA polymerases alpha, beta, and gamma by the 5'-triphosphates of carbovir, 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine, 2',3'-dideoxyguanosine and 3'-deoxythymidine. A novel RNA template for the evaluation of antiretroviral drugs". J Biol Chem. 266 (3): 1754–62. PMID 1703154.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rang H.P., Dale M.M., Ritter J.M. (1995). Pharmacology (3rd ed.). Pearson Professional Ltd. ISBN 0-443-05974-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Balzarini J, Naesens L, Aquaro S, Knispel T, Perno C, De Clercq E, Meier C (1 December 1999). "Intracellular metabolism of CycloSaligenyl 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine monophosphate, a prodrug of 3'-azido-2', 3'-dideoxythymidine (zidovudine)". Mol Pharmacol. 56 (6): 1354–61. PMID 10570065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - MedicineNet.com. Chemotherapy. http://www.medicinenet.com/chemotherapy/article.htm

- US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. "Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Laboratories, 40 F.3d 1223 (Fed. Cir. 1994)". University of Houston -- Health Law and Policy Institute. Retrieved 2007-02-28.